The Memorial for Immanuel Wallerstein (1930-2019)

Joseph Slifka Center for Jewish Life

Yale University

Sunday, Nov. 10, 2019

Shared in excerpts at the event by

Mohammad H. (Behrooz) Tamdgidi

Director, OKCIR (Omar Khayyam Center for Integrative Research

in Utopia, Mysticism, and Science (Utopystics)

Former associate professor of sociology at UMass Boston

A student of Immanuel Wallerstein

I wish to take this moment to thank Kathy Wallerstein for kindly inviting me to this memorial for her father Immanuel Wallerstein and to share a few words about him. I also thank Beatrice Wallerstein and family, Charles Lemert, and others for making this event possible. Thomas (Tom) Reifer kindly informed me first about the sad news of Immanuel’s passing. I thank him.

My spouse, Anna Beckwith, a Binghamton student also of Immanuel Wallerstein and a Braudel Center journal REVIEW staff member in the past, now a senior sociology lecturer at UMass Boston, sent her love and condolences again and apologies for not being able to attend due to teaching obligations.

I am Mohammad Tamdgidi, or Behrooz as called by family and friends, originally from Iran, having lived and worked in the US since coming here to study in 1978.

I am just one among many students who were fortunate to be trained (in my case in the ‘80s and ‘90s) at SUNY-Binghamton’s graduate sociology program, founded by the late Terence K. Hopkins (1928-1997) in lifelong collaboration with Immanuel Wallerstein.

I still cherish each year of my stay at Binghamton, for now I see how important and necessary it was to establish the basic structures of my research, teaching, and overall scholarship philosophy and work during that time. Eighteen years later, I must say that Immanuel Wallerstein and Dale Tomich (chairperson), members of my doctoral committee along with Anthony D. King and my external examiner, the late Jesse Reichek from U.C. Berkeley, were correct in saying following my defense that much of the rest of my scholarly life will involve expansions and revisitations of what I learned during my doctoral studies.

Hopkins had sadly passed away as my committee chair by the time I defended my dissertation in 2001, but its basic framework had been read and evaluated by him and Dale Tomich in an early draft. Immanuel Wallerstein kindly took Terence’s place in my committee, and was supportive of my work both before and after the defense.

Back in January ‘97, I was in the midst again of one of my 10-day meditation/writing retreats at home when I was informed that Terence was hospitalized, and was with him and others when he suddenly passed away. It was a sad and deeply spiritual experience for me, but I was also witness to the depth and extent to which his lifelong friend Immanuel, Beatrice, Kathy, and their family (among others and many students) were engaged and caring for Terence and his dear wife Gloria.

In the concluding banquet of a colloquium in his honor organized by his senior students (Reşat Kasaba, William G. Martin, and Beverly Silver) and Wallerstein in New York City, Hopkins clearly stated who the two most important persons were in his life. Besides Gloria Hopkins, his wife, it was Immanuel. Terence left us first, and he did not of course have the chance to reciprocate being in Wallerstein’s memorial today. But, let me take this moment to symbolically pass around, as a gesture standing for Terence’s presence here for Immanuel, two copies of Mentoring, Methods, and Movements (1998, 2017), the proceedings of that colloquium I republished two years ago in a new edition with the kind support of Immanuel (please pass them around, and eventually to Kathy).

The story of how this book and the colloquium of which it is a report came about is told in the book, but basically Immanuel asked me following Terence’s passing to put together the writings of many colloquium attendees and publish it in his honor, to be dedicated to Gloria Hopkins. I had already been experimenting with my own alternative publishing and press options at the time, and I found Immanuel’s invitation as very meaningful, sincere, and kind-hearted in allowing another student of both to honor their lifelong friendship and collaboration. Unfortunately, I had been unable to attend the colloquium because of traveling to Iran at the time.

Three years ago I thought that the book originally published in 1998 needed further attention and distribution given my more resourceful publishing venues today, so a twentieth anniversary revised edition, including a new retrospective chapter and an extensive bibliography for Hopkins and Immanuel’s work in world-systems analysis seemed like a good idea. Immanuel sincerely agreed with the project. Upon receiving a copy of it, he wrote in an email: “Dear Behrooz, the book arrived here in Paris. It looks wonderful – the pictures and this amazing bibliography, which will permit future scholars to do serious work on Terry. congratulations, yours/Immanuel.”

A memorial is a beautiful occasion to remember dear ones. But, the notion of memorial implies a separation, a distancing, of an observer and the observed (or the memorialized). It implies a person, or associated activities and events, belonging to a past, chunkily separated from the spacetime of those remembering the person or the events. Quantum science no longer regards such a distancing of the observer and the observed as tenable, nor should we have believed so even in our Newtonian worldviews, but unfortunately we did for ideological reasons, as I explain in a forthcoming book (in Jan. 2020) on the so-called quantum enigma.

There are students certainly much closer to Immanuel personally and in scholarship and work than I was. So, they have much more and deeper things to say about him than I ever can. But from the vantage point of my own personal experience, I must say that I really do not see such a distancing or separation between my life and what Immanuel, in partnership with Terence, did in their lives.

For me, they are present and alive every day and moment, each time I sit to read and write, whether memorialized or not. I was deeply inspired by their works, by their examples, both intellectually as well as personally. They were dedicated to what they learned, researched, taught, analyzed, and practiced, in favor of a better world. I am by nature independent-minded, so this should be an added factor in noting how appreciative I am of their intellectual project and in their way of teaching and mentoring their students. I have many examples to draw on, and I wish to point out a few.

One of the most important attributes of Immanuel’s mentoring, to the limited extent I can claim regarding my own, was his support and respect for student’s preference for seeking their own ways of going about theorizing and practicing their craft. As the editor of REVIEW, the journal of the Fernand Braudel Center (FBC), Immanuel and the editorial board published two of my papers drawn from my dissertation, which clearly offered independent and critical notes on two issues, one on the universal primacy of economy informing world-systems analysis, and another regarding the viability of antisystemic model as a movement behavior, where I proposed the new notion of “othersystemic movements,” instead.

In both cases, Immanuel was warmly and open-mindedly understanding of where I was coming from, and appreciated in particular the typology of world-historical forms of imperiality I was proposing in my work, and the way I went about using his joint book with Hopkins and the late Giovanni Arrighi (1937-2009) on antisystemic movements to propose my alternative formulations. My article was titled “Open the Antisystemic Movements: The Book, the Concept, and the Reality.”

So, a rare attribute of Immanuel Wallerstein’s mentoring was that despite any difference of view we may have had, he supported my work since he could see that the deep structure of what I was advancing resonated with the basic thrust and heart of his and Terry’s scholarship and social activism in terms of seeking a better world. Immanuel supported publishing my constructive critique of Marxism and its errors as my first book, Advancing Utopistics: The Three Component Parts and Errors of Marxism, published by Routledge/Paradigm (drawn from my dissertation), even though at points it problematized some of the structures of world-systems analysis in favor of further enriching them. I myself believed that the book was, in its deep structure, in resonance with their works, and thereby deserved being dedicated to him and Terry, because at its heart, we were pursuing the same goal.

This is where another point I wish to highlight about Immanuel Wallerstein’s work should be mentioned. I think he was deeply committed to not seeing his and Terry’s world-systems analysis as a rigid theory or a finally established answer to all and everything. He never failed to emphasize that world-systems analysis was a mode of analysis, open-ended, and flexible in its findings.

Two of my other papers exploring the relation of Eastern mysticism to world-systems analysis were also subsequently published in PEWS (or Political Economy of the World-System) conference proceedings with his support. This is how he was appreciative of the new and different ways students, like me, went about inventing new modes or forms of inquiry. In fact, as it has now become well-known and explicated well by their more senior students in Mentoring, Methods, and Movements (the book I passed around) the very nature of the graduate program they helped build together in Binghamton was to cultivate creative modes and lines of inquiry among students.

I took this to my heart, and experienced, and still experience, every day, the enormous vitality and innovativeness of their pedagogical philosophy and style. We were trained not just to pursue innovative work in specifically given lines or boxes of inquiry as inherited in traditional academia bound in disciplinary structures. At Binghamton, we were asked, we were required, through the hard work of defining our areas of study, to creatively build and invent from scratch new lines and structures of inquiry. We were required to be transdisciplinary, in Immanuel Wallerstein’s word “unidisciplinary,” and not bind ourselves to ready-made, fragmented, and “disciplined” structures of thinking and acting.

At the expense of being told I am turning this memorial moment into a sociology seminar (what can I say, I am still a student of Immanuel and Terence, … and Dale!), let me pass around a copy of a short essay by Immanuel published in 2000 in Contemporary Sociology, American Sociological Association’s book review journal. It is titled, “Where Should Sociologists Be Heading?” While Immanuel wrote and published multi-volumes, I think at times we have to pay close attention to little essays like this one. I did pay very close attention to it, and I wish all of you to have a copy also.

Here, Wallerstein is basically arguing what sociologists need to do in terms of overcoming and transcending a series of dualisms, such as that between theory and history, between economy and polity/culture, between the West and the Rest (or the East), between the so-called neutral objectivity and value-oriented scholarship (which he puts also in terms of the relation of the true and the good), and between the so-called “two-cultures” in academia (the natural and social sciences and the humanities).

Every word of his essay should be cast in symbolic gold to be considered by all and not just those in sociology, for in the essay the basic, deep structure of what (still) needs to be done in terms of overcoming dualistic thinking as the root cause of many problems we all face in the world has been made so evident in his always clear prose.

Adding to the list, though, in this occasion of memorializing Wallerstein, I think it is proper to consider transcending yet another dualism—the dualism of life and death as well. By way of this note, I wish to convey that even whether Immanuel is alive or has passed itself needs to be subjected to our quantum rethinking and questioning beyond its Newtonian, chunky, either/or, considerations.

The creative mode of teaching, inquiry and scholarship Immanuel and Terence advanced took their shape in my own personal experience. I was never a part of the Braudel Center, but was deeply inspired by it, so established instead my own personal research center (OKCIR, Omar Khayyam Center for Integrative Research in Utopia, Mysticism, and Science (Utopystics [with a “y”]) to frame all my post-graduate research, teaching, and professional service.

I was not a part of any of the Braudel Center’s “research working groups” but published my papers in Immanuel’s journal and proceedings with his warm and thoughtful support. I was inspired by his journal REVIEW and therefore, also, independently founded my own journal, Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, which is still thriving, beginning now its monograph series after twelve volumes or 28 issues (some double or triple) of widely read and globally accessible edited collections.

Immanuel’s support in inviting me to design his conference poster on Unidisciplinarity and later publish the Hopkins Colloquium proceedings publication was an acknowledgment of the new ways his and Terry’s student was trying to find his own way and establish his own alternative press—which I did, in my view as an important instance of othersystemic action in line with my scholarly work. So, I persisted in continuing on building my “othersystemic” publishing press.

My point of citing the above examples is to show that for me Immanuel, Terence, and Binghamton Sociology, were not simply people or events of a past to remember, but ways of working, thinking, and acting I live with every day, and will do so for the rest of my life, hoping to pass it on to others as well, as I am doing here. Human architecture, sociology of self-knowledge, utopystics (with a ‘y’ indicating an interest across utopia, mysticism, and science), the fields of study I invented in Binghamton, would have not been even heard of, had it not been for a particular, a creative and innovative, mode of socially engaged intellectual work I learned from and was encouraged to pursue by Immanuel and Terence, and Dale. Of course the fruitful discussions with and the kind support of Anthony D. King in the Art History department at Binghamton on society, space and architecture, ones that nicely continued for me the enormously inspiring teaching and learning I received from my undergraduate studies mentor in Architecture at U.C. Berkeley, the late professor of design and painter Jesse Reichek (1916-2005), can never be chunked out of my learning, for which I am deeply appreciative for they provided further transdisciplinary and creative spacetime for my learning.

Alas, I was looking forward to informing Immanuel of my new forthcoming book (a first volume in a new series titled Liberating Sociology: From Newtonian Toward Quantum Imaginations), where I report having unriddled the so-called quantum enigma.

If you find a sociologist making such a claim (unriddling the quantum enigma!), even as a work in the sociology of scientific knowledge (which it is), to be different, all I would remind you of is how Immanuel, Terence, and Dale (along with others mentioned) trained me in being very attentive to deep structures of thinking, especially of the dialectical method, in the way we go about doing our theoretical and historical work in sociology.

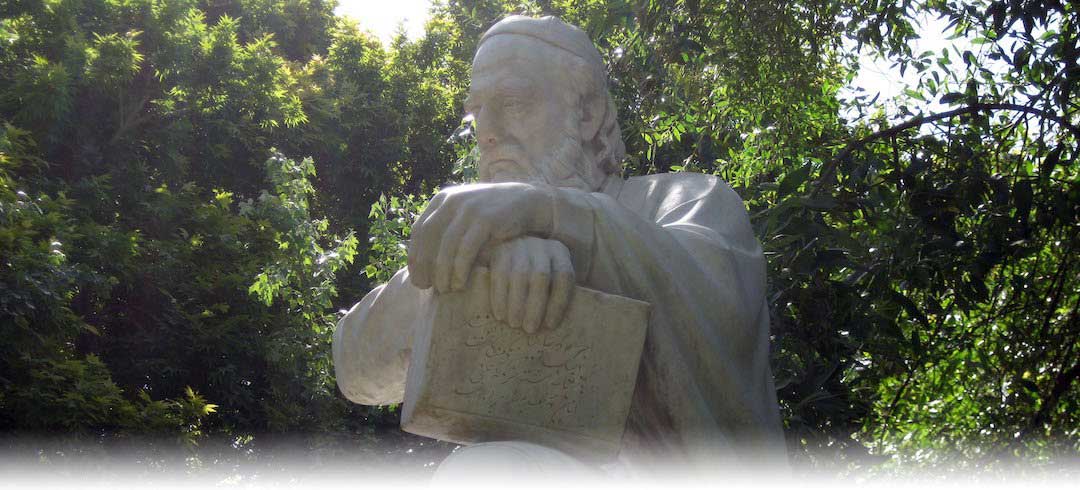

If in a year or two you also hear, in another forthcoming series, that I have solved significant puzzles about the life and works of the enigmatic Omar Khayyam, unprecedented really since his own time nearly a thousand years ago, as an application of the quantum sociological method I report on in my forthcoming book on the quantum enigma, and all this sounds different, it is because I was trained by Immanuel and Terence not to think and work in ready-made boxes and pursue overfamiliarized topics, but transcend them, by questioning the questions themselves, by problematizing, transgressing, transforming, the taken-for-granted borders and boundaries of the disciplines, by exploring new topics in new ways. And if you read these works carefully, you will find that they deeply resonate with the basic spirit and ways of holistic knowing and acting Immanuel and Terence wished that we carry out our works in transdisciplinary and transcultural ways.

So, who is to say they have passed away, since they are quite alive in me and all their students. They have never been a distant particle or event in the past for me to memorialize, since for me there really is no such a thing as a wave-particle “duality” in the light of curiosity and learning I received from them. I am grateful for still being deeply immersed in and riding the waves of their wisdom and teachings.

We learn in sociology, especially in the works of George Herbert Mead, that self and society are twin-born. As simple as this concept may sound, it is in my reading a profoundly quantum notion, defying a dualistically reductive primacy of self over society, or society over self. Mead says they are twin-born. One is the other. They are simultaneous. In quantum theory, the state is referred to in terms of superpositionality, of being superposed, something existing in two or more places at once. As human beings, we are able to relate to each other, or anything, because we are socialized to have selves amid a symbolically interactive system, of which the highest form is our language. I can relate to you because I am able to have a self in me that represents you. So, at once, my relating to you is a relating to myself.

So, whether Immanuel is physically around or not (the particles of whose writings will always be there now forever), you and I are able to relate to him because we each have a self or selves in us that represent him. For some of us, this self is much richer, fuller, and deeper than others. Beatrice, Kathy and her daughter Layla as family are in their very being a continuation of Immanuel, of course. I sincerely believe we would not have had an Immanuel without a Beatrice, and we should always, always, remember that. But for us also, to a lesser extent, we each carry selves in us that have been, are, and will be representing Immanuel and Terence and their colleagues who helped make Binghamton sociology graduate program a utopystic reality for us, as an alternative island of pedagogical innovativeness amid a wider sea of routinized, mechanical, and habitual academic world.

I retired early in 2013 from that old system despite being tenured and promoted, because I had personally experienced in Binghamton, despite any of its shortcomings, how different a program of study can be as an othersystemic exercise in pedagogy and research work, so I did not wish to waste any more of my time in a system so alien to what I had witnessed and experienced at Binghamton. I of course loved and still love (now in writing form) the teaching part of my experience, and many of my students’ best papers in the new sociology of self-knowledge have been published in Human Architecture and are readily readable online. But the university structures as they exist today are still deeply Newtonian, and their problems have been amply studied and reported in other scholars’ works as well as eloquently explained in not only Immanuel’s work in the Gulbenkian Commission, but also by scholars such as Boaventura de Sousa Santos, one of whose excellent papers on the topic was also published in an issue of Human Architecture on “Decolonizing the University,” co-edited with Ramón Grosfoguel and colleagues.

The utopistic (for me also utopystic) experiment of Hopkins and Wallerstein at Binghamton amid traditional university was quite unique and is not just a chunk of spacetime separated from me in the past. It is living with me today. The “odd solidarity” Terence encouraged us to build, one that was exemplified well by his own intellectual and personal friendship with Immanuel, lives in us students as a solidarity with the creative and innovative ways they wished us to live and work. If I may use a metaphor here, the match stick eventually burns and dies in its relatively short-lived body, as all things (including us) do. But the fire Immanuel and Terence ignited in the hearts and minds of their students, in me as well, goes on living and spreading in each of our own ways to the extent we also choose to keep the flames alive, and to that extent they can never be distinguished.

Some spirits never die, and we can find examples of them in waves of meanings received from Persian poets of centuries past whose teachings resonate well in fact with the spirit of world-systems analysis, advanced in favor of understanding our lives as parts of a singular human reality, in the hopes of a better and just world free of all forms of oppression and coloniality. The match sticks of the poets died physically for sure, but is it not wonderful that their fires keep on enlightening and warming our minds and hearts, through their poetry, hundreds of years later?

Then, I close this tribute with a poem from Sa’di and a few quatrains from Omar Khayyam in celebration of Immanuel Wallerstein’s life and works, amid the odd, continuing world-systemic solidarity he fused with his family, Terence, colleagues, and his students. I was very happy to know that Immanuel and Beatrice visited Iran for several university presentations a few years ago, which was received very well by the Iranian academic community. Immanuel’s passing was immediately acknowledged, reported, and his life and work memorialized widely in the Iranian press shortly after his passing.

So, on behalf of Iranians caring for Immanuel Wallerstein from that part of the world, here I recite a few short poems (one from Sa’di and four from Khayyam) in my own English verse translations, in honor and celebration of the wisdom he and Terence Hopkins left for us to absorb and spread.

Adam’s descendants are in frame from one strand,

While in their creation aim as one soul stand.

If a member is in stress from his time’s scar

Others become restless, nearby and afar.

If you’re about others’ griefs and pains carefree

You don’t deserve the name of humanity.

— Sa’di of Shiraz (13th century AD)

I myself searched the world for Jamsheed’s crystal bowl.

Restless days and sleepless nights I spent for the goal.

When teacher disclosed its secret, I learned at last

That Jamsheed’s world-reflecting bowl was my own soul!

From the beginning I searched, by way of the sky,

To find where the pen, tablet, heaven, or hell lie.

Then, teacher advised me, “from the right point of view,

The pen of fate, paradise, or hell is your ‘I.’”

If I had a hand on luck’s tablet, pen, and ink,

I would rewrite it and do what I like and think.

I would cross out world’s sorrows at once and for all,

And fly from such happiness to the heaven’s brink!

Unless we ourselves, altogether, clap our hands,

We will not kick away grief with joy and in dance.

Let’s awake and breathe before the breathing of dawn,

For many dawns will breathe after we’ve had our chance.

— Omar Khayyam (11th/12th centuries AD)

References

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 2000. “Where Should Sociologists Be Heading?” Contemporary Sociology 29(2):306-308.

Wallerstein, Immanuel and Mohammad H. Tamdgidi, eds. 2017. Mentoring, Methods, and Movements: Colloquium in Honor of Terence K. Hopkins by His Former Students and the Fernand Braudel Center for the Study of Economies, Historical Systems, and Civilizations (Twentieth Anniversary Second Edition). Belmont, MA: Ahead Publishing House.

For further information about Immanuel Wallerstein’s life and works, visit his online home. Wallerstein’s wikipage can be visited here.