The founder of the academic graduate studies program at Binghamton University (SUNY), Terence K. Hopkins (d. 1997) was a hidden gem of world-systems studies who contributed indispensably to its foundation amid a lifelong collaboration with Immanuel Wallerstein. The following is an editorial postscript written by Mohammad H. Tamdgidi, for the twentieth anniversary second edition of Mentoring, Methods, and Movements: Colloquium in Honor of Terence K. Hopkins by His Former Students and the Fernand Braudel Center for the Study of Economies, Historical Systems, and Civilizations, co-edited by Immanuel Wallerstein and Mohammad H. Tamdgidi, recently published on Jan. 3rd, 2017, by Ahead Publishing House (imprint: Okcir Press), Belmont, MA.

I. Introduction: Remembering Terence K. Hopkins

As a student of Terence K. Hopkins, I did not have the good fortune of attending the NYC colloquium organized by his students in his honor in August, 1996; I was visiting Iran at the time. However, when Immanuel Wallerstein subsequently invited me to co-publish with the Fernand Braudel Center (which he was still directing at the time in Binghamton) the proceedings of the colloquium following the sudden and untimely passing of Hopkins just a few months later on January 3rd, 1997, I could not be more appreciative and honored. The first edition of the colloquium’s proceedings was co-published in November, 1998.

As a doctoral student of sociology at Binghamton University, I had been attracted alongside my studies to the idea of developing autonomous publishing venues for the kind of alternative visions I was exploring in my research at the time. Immanuel’s gesture in inviting me to collaborate on the co-publication of the proceedings of the student-organized colloquium in honor of Terence was in line with the ways in which he and Terence conducted their mentoring and support of students—by building on the students’ own ways of defining and constructing their identities, studies, careers, and lives. Inviting me to help put together the collection was a kind and beautiful gesture in rounding out the Hopkins Colloquium and publishing its proceedings by involving an alternative, though at the time still preliminary, initiative by one of Terence’s students.

I recall when, a few years before then, I sent a brochure and regular newsletters of the publishing press I had established in Binghamton, NY, in 1991—called Ahead Desktop Publishing House at the time, now continuing as Ahead Publishing House, with an imprint as Okcir Press—I oddly found Hopkins sending me back in mail his usual margin notes on the brochure and the newsletters, offering his support and advice on how to go about building the project. He later gave me some of his margin-noted feedbacks on the newsletters while I was meeting him during “office hours” at his house. He was treating my initiative itself as a “term paper,” this one of a practical nature, to be commented on. Reflecting back on this matter now, twenty plus years later, I am struck by the boundless way in which Terence conceived of the mentoring of his students amid their own on and off campus ways of going about their scholarship and its dissemination toward building what I later called “othersystemic” movements.

Looking back now, I see that Hopkins was recognizing my involvement in building an alternative press to be itself a moment in what he regarded as efforts in appropriating movements. It was a way of turning the usually alienated and alienating conditions of mainstream (especially academic) publishing procedures and industry into ones that empower students, authors, scholars, and activists themselves. Consider how the embracing of such independent publishing efforts by Hopkins (and Wallerstein, of which the two editions of this volume are examples) compares with the stigmatized manner in which the effort is met in usual tenure and promotional review procedures in academia. After all, Terence and Immanuel (and colleagues) had their own experience of building the Fernand Braudel Center and its journal, and must have appreciated the self-empowering nature of those efforts. Claiming the publishing process for the producers of knowledge themselves is an instance of what may be regarded as othersystemic and not just antisystemic efforts in appropriating specific cycles of the publishing commodity chain. It challenges the system not through antisystemic rhetoric, but by the reality of its own alternative presence amid the mainstream (in this case, publishing) culture.

In fact, the independent scholarly journal I subsequently launched, Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge (27 issues of which were published from 2002 to 2013 and are accessible online and through major academic databases worldwide), was inspired and fundamentally grew out of a “class-book” project entitled “I” in the World-System: Stories from an Odd Sociology Class, which my students and I self-published in Spring 1997 (using a hypothetical publishing imprint proposed by a student in the class) while teaching a course at Binghamton following Terence’s passing in January 1997. The book was dedicated to him.

When a part of my dissertation whose preliminary draft Hopkins, as the chair of my dissertation committee before his passing, had marked as “do-able” in his characteristic pencil-marked notes—while, as he told me, traveling on a well-deserved post-retirement cruise ship with his beloved wife Gloria Hopkins—was first published by Paradigm (now a part of Routledge) under the title Advancing Utopistics: The Three Component Parts and Errors of Marxism (2007), I could not think of anything better to illustrate Wallerstein’s concept “utopistics” than by drawing on the pedagogical othersystemicity and utopistics of his lifelong friend and colleague, Terence K. Hopkins. The reflections had been originally presented in my dissertation account, later on being updated and included as an epilogue in Advancing Utopistics.

I recently approached Wallerstein, a few months short of twenty years following the passing of Hopkins in January 1997, to suggest publishing an updated second edition of Mentoring, Methods, and Movements to commemorate his memory and legacy again. I thought this would allow for a wider distribution of the valuable insights contained in the book by his former students about the role Hopkins played in their mentoring and in advancing world-systems studies more broadly. As part of the republication effort, I also wished to improve on its organization (later on found to be in need of an index, a works and citations bibliography for Hopkins, and biographical notes on the contributors which were lacking in the first edition) and to include some reflections of my own, by way of sharing again my earlier essay “The Utopistics of Terence Hopkins” which is included at the end of this postscript. Wallerstein kindly welcomed and encouraged the idea of publishing the second edition.

As I began writing this postscript to the colloquium proceedings, however, I realized that I could also, as a co-editor of this second edition, add a few notes regarding others’ contributions, sharing as well some reflections on my own experience in academia during the past twenty years since I wrote my essay on the utopistics of Hopkins.

II. Sociologically Imaginative World-Systems Analyses

In the essays included in this volume, contributors share, using illustrations from their own experiences of meeting and working with Terence K. Hopkins, their thoughts on whether, why, and how he succeeded in founding an alternative graduate program of sociology amid the mainstream academia.

Just consider what Lu Aiguo shares about her experience as a Chinese scholar and intellectual and how it relates to her experience moving back and forth between Beijing and Binghamton to study in the graduate program. Echoing what Arrighi, Hopkins, and Wallerstein (1989) have argued about antisystemic movements often becoming, upon seizing power, a part of the status quo in the postrevolutionary period and thereby resistant to further social change, Aiguo also argues that, in her view, movements that build their agenda on negative rejections of a system in hopes of a better future have lesser chances of success and survival than those relying on more patient and positive building of alternative social and organizational realities that empower people in the here and now. While Aiguo credits the graduate program in sociology founded by Hopkins for having provided an opportunity for her to deepen her realization of that important point, one should note that in many ways the reality of the graduate program itself as built by Hopkins signifies a self-empowering strategy and example of what Aiguo appreciates for being more effective in advancing alternative pedagogical outcomes.

Walter Goldfrank explains, amid his anecdotal commentary on the importance of rereading the sociology classics, why Hopkins succeeded in building such an alternative pedagogical environment amid the mainstream academia. Reminding us of the centrality of “relational thinking” in Hopkins’s teaching, Goldfrank lays his primary emphasis, when recalling Hopkins’s approach to the agency-structure dialectic, on the side of the agencies’ role in shaping relations and building new social structures. Without this emphasis it would be impossible to understand why Hopkins dedicated such efforts in building an alternative pedagogical enclave amid an existing (academic) world-system.

It would have been much easier, in other words, to resign to the fatalism of an existing academic systemic logic reproducing the wider educational structures of the modern world-system, and follow status quo academic procedures of coursework, doctoral examination, and research. However, by the example of what actually happened, we find a world-systems analysis at work that treats the larger system not as a supposedly functioning monolith but as a contradictory process that offers relatively short-term, small-scale, opportunities in its everyday micro (or even macro, during crisis periods) dynamics to build new “small group” structures—ones that can in time, as Hopkins stated in his own dissertation, undermine long-term, large-scale structures of the system as a whole.

Hopkins’s Columbia dissertation on small groups can thus be regarded as a conceptual dress rehearsal for the building of small, alternative graduate programs in the belly of a larger academic system. And for this, a recognition of the creative role played by the actors and agencies in building new pedagogical structures is crucial. In fact, it is interesting to ask and explore how the subsequent world-systems studies program Hopkins founded in collaboration with Immanuel Wallerstein for the “study of long-term, large-scale social change” depended, simultaneously, on a mastery of knowledge about and the practice of relatively small-scale, short-term, social change in the spacetimes of the modern world-system’s everyday, here and now events—including those going on in the departmental offices, corridors, and class/seminar rooms of its mainstream academia.

Bill Martin significantly asks, for good reasons, “How did Terry do it?” and in doing so reminds us of two things. One, again, is the role of agency (in this case, that of Hopkins) in building new structures in academia and, second, that the other side of the Hopkinsian dialectic of relational thinking is also important for understanding how its large-scale/long-term and small-scale/short-term dimensions co-participate in perpetuating, challenging, or undermining the reality of the world-system. Martin reviews the structural and conjunctural trends in contemporary academia and points to the contradictory dynamics of failed traditional academic models of teaching, research, and department building amid ever more “globalizing” trends in the world-system that continue to open new opportunities for the kind of alternative academic programs Hopkins initiated at Binghamton.

However, Ravi Palat again reminds us, by specifying examples from the questions raised by Hopkins about his doctoral studies, that objectively contradictory conditions of academic life amid a broader global context and the opportunities they may present cannot automatically result in an Hopkinsian agenda without the minute everyday dynamics of mentoring, methodological guidance, and movement inspiration that characterized Hopkins’s pedagogy and the alternative program of graduate study in sociology he built in Binghamton. The subsequent joining of the sociology department faculty at Binghamton University by Bill Martin, Ravi Palat, and Richard Lee (who has also directed the Fernand Braudel Center) following the passing of Hopkins and the publication of the first edition of this volume, itself represents the methodological emphasis Hopkins and his students (alongside other faculty) laid on the role actors and agencies play in the continuation of the graduate program.

Wallerstein offers important insights regarding the unique nature of the pedagogical system Hopkins built at SUNY-Binghamton and the vital role the program played in the emergence and development of world-systems studies itself as a sociological tradition. Wallerstein’s synoptic tract reminds us of the intricate way in which various new threads in Hopkins’s pedagogy were woven into the tapestry of the program he invented at Binghamton. It was the openness and flexibility of the doctoral studies program and how it branched out in diverse ways, for those interested, into the research working groups and activities of the Fernand Braudel Center that allowed for the simultaneous building of new insights and skills among and across the involved faculty and students, and the deepening of discourses that shaped and continue to shape world-systems analysis. Various elements of conventional doctoral program procedures and structures were subjected to radical rethinking and redesign. The emphasis on the inductive procedures of moving from substantive to theoretical and methodological coursework, the mutually engaging dynamics of young and not-so-young scholars, the inventive nature and procedures of sociological specialization and new area study design, the transdisciplinary nature of the historical sociological inquiry advanced, etc., were elements of an alternative pedagogical system that offered coherence and an autopoietic logic to the new graduate study program—novelties that, as Wallerstein notes, are yet to be recognized for their worth in advancing critical and engaged social scientific and sociological knowledge.

The contribution by Beverly Silver reminds us of the close attention that was required from Hopkins’s students to appreciate the feedbacks received from him—comments that only revealed their value in persistent reading and rereading/reconsideration of his words (and/ or silent gestures). She also reminds us of the self-critical spirit of Hopkins’s pedagogy, inspiring students to be always on guard for not taking any ideas, including Hopkins’s own words elsewhere expressed, for granted as applicable in advancing particular research endeavors.

It is noteworthy that among the recollections of Hopkins’s students of their studies at Binghamton, the minute dramaturgy of personal interactions performed by Hopkins are as much recalled and cherished as the more substantive issues discussed in those interactions. While such “personal recollections” may seem marginal to the substantive discussions of world-systems analysis, I think it is worth considering—in terms of their mentoring, methodological, and movement-inspiring import considered within a Millsian sociological imagination framework—how personal troubles and public issues of learning are intimately interrelated, and their neglect often a cause of failures by social movements in appreciating the humanist content of their efforts at social transformation.

Commentaries by Reşat Kasaba, Richard Lee, and Phillip McMichael, as well as those by Rod Bush, Nancy Forsythe, and Evan Stark (plus Lu Aiguo, as commented on previously) offer important self-critical opportunities for world-systems analysis to continually rethink and reinvent itself.

Kasaba reminds us of how Hopkins did not dualistically separate the personal from the world-systemic in his pedagogy, and from the experience of his teaching about methods and movements. On the contrary, he illustrates well how for Hopkins the trees were the forest, and what made the forest worth understanding, improving, and recultivating. Kasaba shares the mentoring advice he received from Hopkins in terms of cultivating an ability to sift the crops from the weeds in anything we learn, including those offered by world-systems analysis, highlighting the need for adopting self-critical approaches to developing its concepts and analytical frameworks.

Richard Lee emphasizes the need for considering newly emerging insights on the nature of knowledge in an era marked by transitions beyond Newtonian scientific paradigms, in favor of imaginative, creative, and artistic practices of knowledge production and scientific inquiry. He particularly reminds us of the emergence of new scientific imaginations characterized by the erosion of objective/subjective dualism previously shaping our knowledges of systems.

McMichael turns the opportunity of his presentation into a research-sharing experience inspired by Hopkins, offering an example of how by being self-critical and open to questioning the inherited concepts and theories of labor, we would be able to consider more effectively how wage labor may be reconsidered in a new global context marked by the increasing predominance of informalized labor as the new “pedestal of capitalism.”

And the late Rod Bush, who sadly passed away in 2013 following decades of activism and scholarly contributions in the area of race studies and Black Liberation movement, offers valuable insights on how his own intellectual development was shaped by his meeting Wallerstein and Hopkins and the openness with which he, as a mature student returning to academia, exchanged views and learning with them. The self-critical approach to mentoring, methods, and movements Bush learned in the program offered him an opportunity to rethink his activism during his doctoral studies in ways that he found transformative and consequential for his many years of research and activism to come.

I think the self-critical insights offered by Elizabeth Petras, Nancy Forsythe, and Evan Stark in encouraging world-systems analysis to take more seriously questions of place/space, of gender, domestic violence and of problems with academia itself, further add value to this collection in advancing world-systems analysis as an open and self-reinventing scholarly tradition.

What Petras argues for is a world-systems analysis that pays attention to the specificities of space and place in shaping the identities and motivations of actors, small or large, amid diverse social, political, and cultural contexts. We should not forget, after all, that it was the opportunity opened up in a “place” called Binghamton that allowed for decades of scholarship from which world-systems analysis itself emerged and the specific scholarly culture and identities of its adherents shaped and reshaped.

Forsythe offers a rigorous and fascinating argument, worth many rereadings, for taking gender and women’s studies seriously, for it radically points to the need for revisiting the “unit of analysis” debates and discussions that shaped the structures of world-systems analysis itself. She argues that serious consideration must be given to incorporating discussions of self and society, the personal, and the private, in the foundational structures of world-systems analysis. In many ways, this is a further and deeper extension of Petras’s argument for appropriating the discourses of cultural place, space, and of microsociology for world-systems analysis, by expanding their notions to the inter/intrasubjective spacetimes of personal life that necessarily involve intimate questions of gender and sexuality.

Evan Stark’s vivid biographical reflections on issues of domestic violence and battery in women’s lives and studies offer further insights about how world-systems analysis is not just about “long-term, large-scale social change” but also, simultaneously, about the short-term, small-scale dynamics of personal self-knowledge and change in everyday here and now, and that the two can never happen apart from one another, so long as we consider the key role played, amid a dialectical and relational context, by agencies and actors in building alternatively better, utopistic futures amid and beginning from the presents of the modern world-system.

However, Evan Stark’s contribution stands apart from others in the volume in that he subjects academia itself to serious criticism, revealing the political and social constructedness of academia in highly graphic and personal terms, in order to make us aware of how often we take the university itself for granted, even when we acknowledge the unique and liberating ways in which Terence K. Hopkins personally and/or administratively outmaneuvered the academic system to make way for alternative mentoring, methods, and movements.

The questions that arise in my view from this latter vantage point are: should one always assume that the kind of experiment Hopkins and his colleagues led at Binghamton can and should be emulated at any cost as part of academia elsewhere? Should we be led to the conclusion that the only and the best way to pursue Hopkins’s legacy is to remain in academia at any cost and try to carve out similar spacetimes, no matter how temporary, for advancing liberating world-systems analyses? Would we, or should we, be looking down upon those who find “academia,” “scholarship,” and “sociology” to be much wider in scope than that found in their inherited institutional forms? Should we continue to regard universities and sociology departments as the primary, the pivotal, structures or arenas of knowledge production and dissemination so that we end up, like Hopkins, dedicating our lives to carving “makeshift trenches” amid them to bring about social change? And consider all the above while being aware of world-systems studies, such as those conducted by Wallerstein and Hopkins themselves, that shed important critical light on the structural limits of modern academia and its narrow and fragmented disciplinary organization and dichotomized science/humanities cultures, acknowledging the diminishing roles played by universities in the process of knowledge production and dissemination in the world today? Can alternative futures emerge from mainstream university realities, no matter how critically approached, or do they require (as well) experimenting with and building alternative university (research, teaching, and publishing) realities off the mainstream campuses?

Here, it may be helpful to briefly share my own thoughts on and experience in academia since graduating from Binghamton.

When I was completing my doctoral studies at Binghamton, I was quite ambivalent about pursuing an academic career. Having witnessed from a student’s standpoint the politics of the department, I wondered much about whether an academic job was something I should pursue. It was in consideration of advice from another dear advisor from my undergraduate years, Jesse Reichek (who also sadly passed away in 2005), and the practical example of Hopkins’s experiment in academia, that I found myself encouraged to give academic career a try, which resulted in joining the sociology department at UMass Boston in 2003 as a tenure-track faculty (following two years of full-time lectureship at SUNY-Oneonta and other teaching opportunities at Binghamton University previously).

Without the inspiration from Hopkins, one that essentially involved a commitment to regard mainstream academia as an arena for initiating new opportunities for alternative pedagogy, research, and practice, I would not have launched the kind of projects that helped me find my academic experience to a considerable extent enjoyable and rewarding—such as developing Millsian sociological imagination approaches to teaching and mentoring students and cofounding and launching an internationally recognized annual conference/publication series (the Social Theory Forum) at UMass Boston that during the initial four years of my involvement advanced transdisciplinary and cross-cultural sociological discourses and publications by revisiting the works of Paulo Freire, Edward Said, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Frantz Fanon.

However, I also personally experienced, first-hand, the oppressive aspects of mainstream departmental life that were often excused and enabled by a broader university system despite the friendly front-stage behaviors of some of its faculty and administrators. I often asked myself how much of the bitterness of my experience as a tenure-track and then tenured faculty at UMass Boston was a result of the behaviors of a few “bad apple” faculty members mixed in with several other tenure-track and tenure-trapped faculty who wished not to rock their boats to formally acknowledge even basic facts of administrative abuse, let alone the verbal and personal kinds. However, I was also reminded time and again of the structural embeddedness of most (if not all) such abusive, or abuse-condoning, behaviors on the part of academic actors who otherwise, in their annual faculty report reviews, remained duplicitously appreciative of the contributions of their hard working, “impressive,” “outstanding,” and “excellent,” “wonderful junior faculty.”

The fact is that in my academic experience I came to a deeper understanding of the tenure system as a panoptic trap that often serves well the functional needs of a mainstream academia for marginalizing, or at least tolerating and domesticating, if not silencing, alternative mentoring, methodological, and movement visions and energies of their new faculty. This is made possible by means of maintaining two-faced front-stage appreciations and back-stage stigmatizations/devaluations of critically-minded faculty efforts through, among others, pseudoscientific mechanisms of “academic reviews.” And this is not simply a departmental or university practice, but extends to long-established, outdated “peer review” procedures that serve panoptic mechanisms of overt gate-keeping and subtle self-censorship that ignore, silence and marginalize subaltern voices under the guise of “scientific” academic review and evaluation procedures.

I am not against universities and academic ways of learning, generally considered. I have benefited from them, and hold degrees from it, though I do credit my academic experience to unconventional teachers such Hopkins and Reichek, among others, who practiced their mentoring in ways that are not typical for mainstream academic institutions. There is nothing wrong with conducting organized and collective efforts in science and search for truths. They are essential. But scientific pursuit does not take place in social, cultural, political, economic, and historical vacuums. The particular institutional and cultural forms in which the pursuit of scientific knowledge is organized can have significant contributive or fettering effects on the advancement of knowledge. This is especially the case when alternative and potentially more fruitful and liberatory modes of knowledge production and dissemination have appeared on our social horizons and may be already at hand but not embraced due to the perpetuation of outmoded habiti of intellectual and academic work.

I am proud of having passed my tenure review based on my own records of research, teaching, and service despite such outmoded structures prevalent in academia, and the ill-will of a few. However, I decided to retire early following my tenure and promotion so as to not waste more of my life, instead pursuing independent scholarship using the structures of research and publication I had wisely continued and further developed parallel to my academic work via OKCIR (The Omar Khayyam Center for Integrative Research in Utopia, Mysticism, and Science (Utopystics)) and Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge. I consider these—and the very way in which I created from scratch at Binghamton (and still continue to purse) their associated three-fold fields of research inquiry—the most important fruits of mentorship, methodological insights, and alternative movement interests I critically received from Hopkins.

Looking back, the advice and inspiration I received from Reichek and Hopkins in giving my academic career a chance served its purpose. It allowed me to experimentally gain an insider, intimate and personal, experience of academia as a tenure-track and then a tenured faculty. It also allowed me to experiment with alternative and liberating models of teaching, research, and service in collaboration with my students in the classroom and empathetic colleagues in other departments on campus and in other universities worldwide. However, in the process I also understood more intimately the nature of the sacrifices that mainstream academia demands from its actors, leading me to realize in a personal way that critical scholarship, mentoring, methods, and movements are not supposed to, and should not, be confined to university departments trapped in panoptic and intellectually incarcerating university systems and procedures. Utopistic universities do not have to always be confined in, nor spring from, rigidified academic structures as habitually associated with the university campus “places.” Today, more than ever in consideration of the digital revolution and the information age, there are increasing opportunities to liberate ourselves from the habita of outmoded “uni”versity structures in favor of embracing new models of pluriversity that may include, but do not have to be confined to, the mainstream academia (for further discussions on this theme see the 2012 edited collection of Human Architecture on “Decolonizing the University: Practicing Pluriversity”).

It is in light of the above that I now read back into the utopistics of Terence K. Hopkins and appreciate the essential point of his legacy and coda. When he refers to his hope in movements, he is laying an emphasis on the hope (and not just a fatalistic belief, no matter how deep) for acting agencies to creatively question and transform inherited social structures and institutions that have consciously or subconsciously appropriated them, on or off campus. It is up to us, therefore, individually and collectively, to reappropriate, creatively, what defines our pedagogy, scholarship, and movements, and these can originate from or take place, but do not have to remain, within the bounds of traditional academia and its campuses.

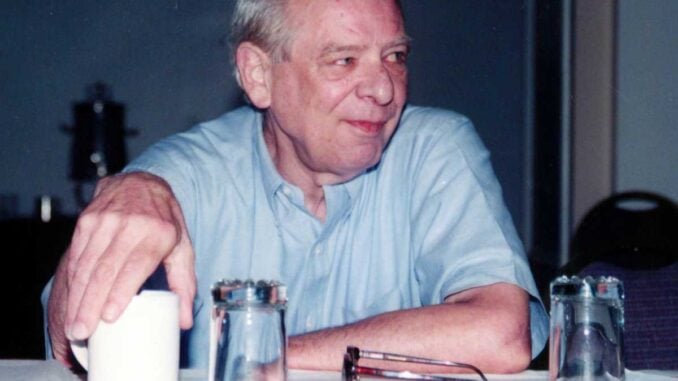

I can now more fully appreciate the depth, rigor, uniqueness, creativity, and odd solidarity that characterized the program of graduate studies as founded by Terence K. Hopkins, a solidarity that includes loving and still enduring solidarity and friendships I established with my dearest friend and spouse, Anna Beckwith, and lifelong friends Satoshi Ikeda and Yoshie Hayashi, also close students of Terence, and other students, brought together through “enrollment” in his initiated program. The former students in this volume represent only a part of a wider community of students who benefitted from their interactions with Hopkins, many of whom took part in a lively and festive evening dinner gathering following the formal seminar sessions. I thank Terence for the gifts of these friends, and the generations of students and colleagues, distant or close, who found one another through his program.

As I have stated previously and elsewhere, I think world-systems analysis can significantly benefit from revisiting its formative debates on the question of its proper “unit of analysis.” The critique world-systems analysis persuasively launched against dependency and modernization theories—arguing that adequate understanding of any parts of the system cannot be achieved without an understanding of the system as a whole—can itself be applied to recognizing the limits of world-systems analyses that regard any historical world-system (including the modern world-system) to be understandable apart from human world-history as a singular whole and process. This will help us move away from Eurocentric and economistic macrosociological assumptions that result from a narrow focus on the modern world-system and lead one to assume that the latter can be understood on its own and apart from the larger-scale, and longer-term reality of the singular world-historical development of which it has been only a part.

On the other end, at the micro level, recognizing the social and cultural constructedness of the notion of singularity of the human “individual” can lead to fruitful investigations of the contradictory nature of human selfhood, and the significance of selves (and not presumed singular individuals) as the proper micro units of analysis of acting agencies involved in (or not) in small-scale/short-term and long-term/large-scale social change, intra/intersubjectively and more broadly in society at large. In other words, it will be fruitful to question whether presumed “individuals” (and/or groups of them) rather than selves amid fragmented and divided intra/intersubjective landscapes are the proper units of analysis and action on the micro side of the Hopkinsian agency-structure dialectic and relational thinking.

Adopting an approach to the “unit of analysis” that transcends a dualistic conception of the long-term/large-scale and short-term/ small-scale in favor of a relational, dialectical unit of analysis in which the singularity of world-history in the macro and the multiplicity of personal selfhood in the micro spheres are continually recognized can offer a richer, and more fruitful, opportunity for the development of world-historically and personally self-reflective world-systems analyses and actions. It will allow for the development of Millsian sociologically imaginative world-systems approaches to mentoring, methods, and movements. It can also lead to a deeper appreciation, by the way, of the role scholars such as Hopkins have played in the genesis and development of new world-systems analyses and perspectives. Gathered in this volume itself, in fact, are sociologically imaginative world-systems analyses of Terence K. Hopkins amid the world-historical public issues that deeply troubled him personally and are even more prevalent today. I often wonder what would have happened if C. Wright Mills, that other Columbia University faculty, had survived an early death and joined his colleagues Hopkins and Wallerstein in fusing a common, sociologically imaginative world-systems analysis.

Cultivating sociologically imaginative approaches that allow us to simultaneously consider personal troubles and public issues via a reconsidered unit of world-systems analysis—one that frames such an approach in terms of the macro/micro dialectic of singular world-history and multiple personal selves—promotes respect for the diversity of cultures and the diversity and psychological complexity of personal actor roles and associated selves that continue to become involved in mentoring, methods, and movements. Such a dialectical simultaneity of macro-micro units of analysis indeed can reveal the contributions of all those attending or contributing to the TKH Colloquium, whether or not their presentations were delivered or included in this volume. The photo gallery included in this volume offers a glimpse of a much wider community of scholars, activists, and friends who shared in Hopkins’s life story and work accomplishments.

Hopkins stated clearly in his last days (and also at the end of the colloquium) who the dearest two individuals were in his life, Immanuel and Gloria. And for Immanuel, the same also holds for the role played by Beatrice in his life and works. These micro realms of domestic life, love and friendship were and are as much a part of the story of world-systems analysis and contributive to its founding and continuity. A world-systems analysis that is mindful of both the long-term/largescale scope of world-history and the relatively shorter-term/smallerscale intra/interpersonal relationships of love and friendship among family and friends; of young and not-so-young scholars; of the more senior students at Columbia and Binghamton, and the less senior students celebrating Hopkins’s dinner gatherings at the colloquium and elsewhere with his wife Gloria especially before and during his last, post-retirement months; of the lives of close colleagues such as the late André Gunder Frank (d. 2005), Faruk Tabak (d. 2008), Giovanni Arrighi (d. 2009), Rod Bush (d. 2013), and Cedric Robinson (d. 2016), who were all present at the 1996 colloquium but are sadly no longer with us; offers a richer and sociologically more imaginative depiction of the life Hopkins lived and the work he accomplished amid the odd solidarity of the community he helped build during his lifetime.

When I was preparing this second edition of Mentoring, Methods, and Movements and including the original text of the program announcement of the 1996 colloquium at the beginning of the photo gallery included in the volume, I was struck by an exclamation mark (!) in the announcement text written by the organizers, one that followed a reference to Hopkins’s doctoral dissertation. It reads:

… And he completed a brilliant dissertation on small groups (!) in 1959.

I chose not to edit out the exclamation mark in the announcement for the gallery inclusion, since it illustrates well in a nutshell whether, why, and how Hopkins succeeded in building an alternative graduate program amid mainstream academia to help launch and advance world-systems studies in collaboration with Immanuel Wallerstein and colleagues. What appears as an oddity, and a seeming divergence from what world-systems analysis appears to be, is actually a hidden pearl inside its shell as a whole, if we remind ourselves of the Hopkinsian hopeful primacy of acting agencies in relation to social structures. The program of study of “long-term, large-scale social change” at the macro level indeed could not have advanced, and cannot in my view effectively advance, without simultaneous attention to the everyday “short-term, and small-scale” dynamics of inter/intrasubjective social change at the level of small groups of persons and selves at the micro level, of which the graduate program Hopkins founded offered an example.

The exclamation mark indeed sums up, in a lived way, the life and contributions of Terence K. Hopkins, offering us cherished memories of new seeds to cultivate and crops to harvest in further advancing and deepening world-systems analysis.

III. The Utopistics of Terence K. Hopkins

Wallerstein’s concept “utopistics” is innovative and consequential, since it marks an important break from long-held (Marxian or other) traditions that tend to dichotomize utopianism and science as different and mutu ally exclusive practices. Revisiting the dualism of utopia and science as such points to the value of utopistics as an important contribution world-systems studies can make in favor of sober social analysis and transformation, bearing significant implications for critical and applied sociology and historical social science, including the field of critical pedagogy.

What made Hopkins’s pedagogy utopistic and “othersystemic” were his efforts at the construction of alter native realities of sociological pedagogy despite and amid the everyday life of mainstream academia. In the alternative aca demic spacetimes he creatively built, Hopkins uniquely exercised the dialectics of scholarship on long-term, large-scale social change on the one hand, and the personalized dynamics of sociological pedagogy within the “small group”1 of his students and colleagues, on the other. Hopkins’s efforts at building an “odd solidarity” among his students and colleagues were an innovative experiment in humanist utopianism in the realm of academia, a “utopistic” approach to challenging the world-system that was not limited to reactive and merely oppositional modes of antisyste micity, but went beyond it to self-creative and autopoietic constructions of new, and substantively real, academic environments within which new theories and praxes of social change could be developed and exercised.

As the founder of the graduate program in sociology at Binghamton University (SUNY), Hopkins created a new and unique program which offered space and resources to many activist-scholars from around the world to join the program as students and faculty in order to develop the intellectual tools necessary for critical global understanding and transfor mation. Hopkins had a dynamic grasp of the relationship between ideas and reality: that ideas, especially of the academic and intellectual variety, do not spring from thin air, but out of people’s experiences. Refusing to create a traditional and conventional graduate program where students are treated as goods on the assembly line of academic production digest ing other scholars’ knowledge or research fields ready-made, Hopkins built a program that encouraged students to creatively design their own areas of scientific inquiry rooted in their own scholarly interests and findings and based on their personal and communal life experiences. Hopkins helped articulate students’ own voices. This was a radically different teaching approach. He guided students while believing in their ability to change themselves and the world.

Hopkins did not accept, and thus transformed, the academic environ ment that he entered. He was humorously fond of portraying the gradu ate program as a “guerrilla fighters’ camp” for building cadres in the struggle for “long-term, large-scale social change.” As a cofounder of the world-systems perspective, Hopkins was deeply aware that the modern world-system cannot be transformed in the absence of globally constituted movements whose members are trained to understand the nature of capitalism as a world-system. What was unique about his approach, however, was that he did not separate the struggle to transform the modern world into a just and humane system from the pedagogical dynamics of training his students. Although for him such a pedagogical style could not be borrowed ready-made from the existing academic institutions, he did not advocate abandoning the institution simply because it was a functioning part of the world-system itself. On the contrary, he advocated active engagement to creatively carve out of the academic environment such a clandestine camp where new pedagogical approaches and educational systems could be experimented with and formally established, even for a short duration as in a “makeshift barrack.” Hopkins’s ingenuity consisted in the fact that he actually and formally established such a new pedagogical environment in the graduate program. For him, the graduate program represented not just an antisystemic movement in the academic field, but in fact a new social and educational system in its own right.

The essential ingredient of Hopkins’s new approach to building the graduate program was flexibility. The flexibility of the graduate program was a direct result, and logical consequence, of its founder’s attempt to build an alternative pedagogical system within the academia. How can one challenge the rigid academic system which is resistant to change with an equally rigid and inflexible curriculum?! Hopkins built flexibility into the very core dynamics and self-identity of the new graduate program. In this new system, the system did not dominate the individuals, but was created so as to serve the needs of the individuals. Students were treated by him with personal respect as human beings, and not just “students.” Hopkins was deeply respectful of students’ integrity as whole persons, never judg ing them on the basis of the nature and tempo of their academic progress. Implanting guilt feelings among students who could not follow the “normal” content or temporal guidelines of progress in the department for any reason was characteristically alien to his pedagogical style. Students were treated as “young scholars” who come to the department to collaborate with the “not so young scholars” (faculty) in carrying out social research. They were empowered to form their own study committees (with the consent of the latter), and to be able to unilaterally remove any faculty member from the committee when they so decided through the mere submission of a written note to the departmental secretary.

In Hopkins’s world, the academic “social relations” served the per sonalized intellectual growth and development of the students’ (and fac ulty’s) “productive forces,” rather than the opposite characteristics of the “assembly-line” and “fast-food” procedures rigidified in university cur ricula elsewhere. As a cofounder of the world-systems perspective, Hop kins was consciously aware of the need not to impose his or anyone else’s viewpoint as the canon of truth on any student in the name of educating her or him. As the director of the graduate program he knew how impor tant it was not to allow differences of opinion with either student or fac ulty affect the proper conduct toward and guidance of the student. Beyond this he was an advocate for student voices in the program’s relation to the university administration and worked to ensure that university rules met the needs of the students’ intellectual and political growth, rather than the other way around. In Hopkins’s world-system, human beings rule the system, flexibly molding it to foster their intellectual productivity, not vice versa.

The most important and innovative manifestation of the flexible nature of Hopkins’s pedagogy was the design of the program’s guidelines and procedures for students’ demonstrations of competence for doctoral candidacy.

Refusing to follow the “normal” procedures in academia that, as a rule, require students to choose this or that pre-designed field within their host academic disciplines, Hopkins introduced the odd procedure of requiring students to creatively carve out, design, and demonstrate competence in their own personally defined areas of inquiry based on their sociopolitical and intellectual backgrounds and scholarly interests. This procedural innovation was deeply informed by the historical sociological methodology in whose instruction he himself specialized. The definition and conceptions of scholarly concentrations therefore became liberated from abstract theorizing and institutionally rigidified canons of scholar ship. He helped liberate sociology through a procedural innovation that is yet to be recognized by the academic community at large. Scholarly concentrations were made historically and biographically grounded and rendered theoretically flexible to serve the interest of long-term and long-range interpretation and transformation of an ever changing world-systemic reality. Inviting various scholars from diverse disciplinary backgrounds, Hopkins encouraged a method of research that was, to use Wallerstein’s term, “unidisciplinary,” not recognizing the rigidified disci plinary boundaries inherited from the past. The spatiotemporally singular world-system required, in other words, a unidisciplinary approach to intellectual inquiry which began from the fundamental premise that a holistic approach to understanding the reality of the world was not just a matter of preference, but of necessity.

Hopkins’s innovative approach to scholarly inquiry, his personal care, empowerment, and regard for students in the program, his holistic approach to disciplinary boundaries in academia, and his emphasis on the historical sociological method as a necessary approach to sociopolitically oriented research work, could not have been possible in a rigid academic environment. Only a flexible curriculum and organizational structure could sustain a creative tension between students and faculty, theoretical and historical research, empirical and theoretical/methodological areas of inquiry, and between the inner departmental affairs and external sociopolitical pressures and requirements of the rigid inter-academic system. The dialectical (read, in Hopkins’s words, “relational”) flexibility, and the ability to sustain and productively harness dialectical tensions, was essential for the pedagogical style of scholar-activists whose mission’s success depended on the productive harnessing of the dialectics of theory and practice for purposes of long-term, large-scale change in the modern world. The graduate program was in fact the progressive realization of Hopkins’s idea of a makeshift camp for the training of self-conscious, socially concerned, dedicated activists. And to the building of this new, this “odd” and flexible, academic and social movement Hopkins devoted his life.

To his students, Hopkins bequeathed a rich methodological vocabulary to study the dialectic of the very large and the very small, and a rich expe riential vocabulary that, through the exercise of his own humanist utopis tics in pedagogy, instilled confidence in them that the exercise of such dialectical utopistics is a “do-able” project. In a context of concerted efforts in the mainstream academia to increasingly incorporate or close out the makeshift trenches of academic creativity, flexibility, and resistance, it would be a great loss not to continue to decipher and expand upon Hopkins’s legacy in humanist utopistics, especially in the realm of pedagogy and praxis.

The intellectual achievements of world-systems studies can hardly be separated from the flexible organizational realities which made such contributions possible during the several decades it was launched— realities which would not have been possible without the dialectical tensions Hopkins endured personally as the founder and director of the graduate studies program in sociology at Binghamton University (SUNY).

Coda

1. In his dissertation on The Exercise of Influence in Small Groups (1959), Hopkins seemed to have already been interested in the dialectics of the very large and the very small, and the potential transformative powers of the small group vis-à-vis the world-system. He concluded his treatise by stressing that: “Any type of social system can tolerate a certain degree of deviance. For each type a characteristic range exists within which the activities of the participants may depart from the norms of the system without occasioning any basic changes in the structure of the system. Departures outside of this range do, however, occasion fundamental structural changes, even, possibly, the dissolution of the particular system” (183).

References

Arrighi, Giovanni, Terence K. Hopkins, and Immanuel M. Wallerstein (1989). Antisystemic Movements. London; New York: Verso.

Hopkins, Terence Kilbourne (1959). “The Exercise of Influence in Small Groups.” Ph.D. Dissertation. New York: Columbia University.

Tamdgidi, Mohammad H., Editor and Contributor (1997). ‘I’ in the World-System: Stories from an Odd Sociology Class. Selected Student Writings, Soc. 280Z: Sociology of Knowledge: Mysticism, Utopia, & Science. Binghamton, NY: Crumbling Façades Press.

Tamdgidi, Mohammad H. (2007). Advancing Utopistics: The Three Component Parts and Errors of Marxism. New York and London: Routledge/Paradigm.

Tamdgidi, Mohammad H., Capucine Boidin, James Cohen, and Ramón Grosfoguel, eds. (2012). Decolonizing the University: Practicing Pluriversity. (Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, X, 1, Winter). Belmont, MA: Okcir Press.