The following article, titled “Abu Ghraib as a Microcosm: The Strange Face of Empire as a Lived Prison,” by Mohammad H. Tamdgidi, was published in the journal Sociological Spectrum, vol. 27, issue 1, 2007:29-55.

In the article, the author deconstructs the notion that we, as global spectators of the Abu Ghraib prison abuses by the occupying U.S. prison guards in Iraq, were any less abused and subjected to imprisonment than the prisoners themselves. Comparatively drawing upon the ideas and works of social theorists and philosophers such as Jacque Derrida, Michel Foucault, Dorothy Smith, Edward Said, Immanuel Wallerstein, Gloria Anzaldúa, and G. I. Gurdjieff, among others, he problematizes the notions of uniqueness and strangeness of Abu Ghraib experience as a special case, and argues that Abu Ghraib was a microcosm, displaying the strange face of empire as a lived prison.

He further contrasts the photographic images of Abu Ghraib, representing the oppressive practices of abuse by an imperial self (or set of selves), with excerpts from the documentary film Derrida (2002) about the life and ideas of the late philosopher Jacques Derrida (1930-2004). The purpose is to use his taped images and conversations as a reverse gaze by Derrida on our lives from behind the TV screen, questioning our taken-for-granted and dichotomized notions of the world and of ourselves. Derrida is used to deconstruct our prison walls of long-held emotional and conceptual assumptions about the Self and the Other—and how they relate or could relate to one another in the contrasting contexts of imperial versus liberating practices.

The author then elaborates on a need to move beyond the predeterministic and Cartesian social spacetimes of Newtonian sociologies to embrace and foster the strange and creative vantage point of quantum sociological imaginations in our efforts to comprehend the unfolding events of the 21st century as it shapes, and may be shaped by, our everyday personal lives. He ends with a discussion of the research and pedagogical value of what he has called the sociology of self-knowledge, concerned with liberating autobiographical research and teaching in comparative, global, and world-historical contexts.

In Tamdgidi’s view, “Empires and Saddams (or Bin-Ladins) are two faces of the same coin. The West sees itself as a beauty, desperately seeking to cleanse the faces of the beast on the wall of the East, not realizing that the wall is a mirror, and the beast’s reflections by-products of its own colonial adventures across world-historical spacetime. Abu Ghraib does not signify the strangeness of a local imperial prison in the here and now; it also expresses the strangeness of a horrendously disgraceful imperial metanarrative still telling and shaping world-history.”

This original journal article published in Sociological Spectrum can be accessed here. The journal issue as part of which the article was published can be accessed here.

Abu Ghraib as a Microcosm: The Strange Face of Empire as a Lived Prison

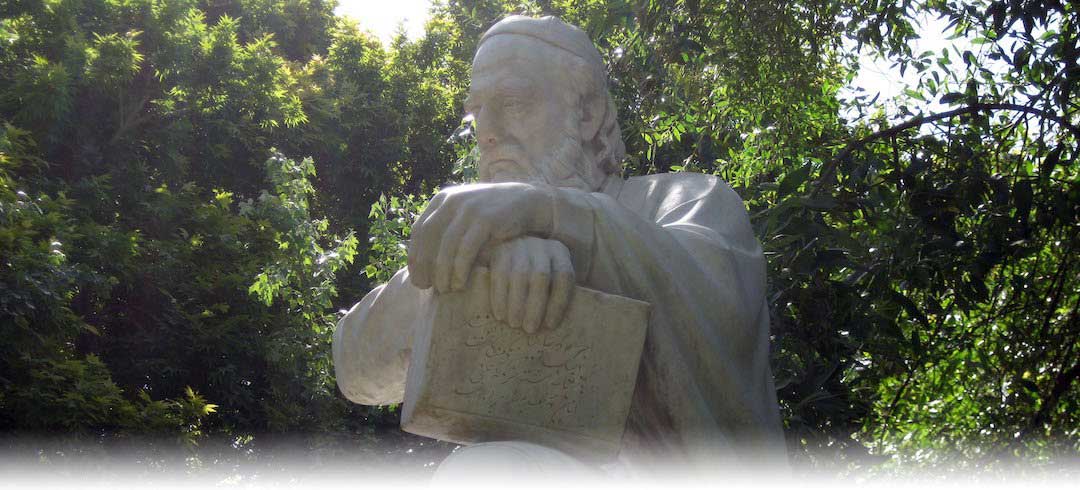

I shattered on the stone last night a glazed blue Jar.

I was drunk, so my thoughtlessness had gone too far.

The jar said in the heart’s Tongue: “You’ll be broken too

Just as I was whole yesterday, like now you are.”

— Omar Khayyam (Tamdgidi translation)

I. Introduction

A few years ago, past 9/11, I had a strange experience. I was being treated by an occupational therapist for lingering sharp pains in my hands. The treatments involved going to a clinic several times a week, for several weeks, and sitting there for about an hour while battery-charged wires were attached to my fingers to help absorb medicine into my aching muscles. Every time I did this, however, I had a strange feeling of identification with the highly-publicized image of the terrified Abu Ghraib prisoner with fake wires attached to his hands and a hood on his head while standing on a cardboard box. Each time, I had a strange mixture of horrible feelings about and amusement for the irony.

But the strangeness of the experience did not end then. Being the ‘good’ patient that I was, one day the occupational therapist began the session with an even stranger offer. She said they were in the midst of an advertising campaign for the clinic that involved putting large posters of their actual patients—while being treated—on the walls of a local hospital. She asked me whether I would be willing to volunteer to be on the posters. I could not have felt more bewildered, if not amused. Doing my best not to offend her for what surely was an innocent offer, I told her quite diplomatically what I had felt before and that I would not feel comfortable being permanently displayed as a man of Iranian and Middle Eastern descent with wires attached to my hands and staring at the camera with an innocent submissive smile. (Covering or hiding the face would certainly not have made the situation any less analogous.) Sympathetically reacting in shock and talking aloud to herself, she replied, “Oh, why did I not see the connection!” Expressing apology, she then proceeded to note—intended as a consolation, I am sure—that I may have been taken as a Latin American! I shook my head as if trying to awaken from a strange dream.

When soon after this incident I was invited to participate on a panel in the 75th Annual Meeting of the Eastern Sociological Society in March 2005, exploring the social psychological meaning of abuses and atrocities committed by the U.S. prison guards at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, I could not help but think of the strange experience I had just had at the clinic. Strangely so, since the word “Abu Ghraib” in Arabic (or Persian) literally means “father of the strange (or of the stranger)”—conjuring notions of strangeness and estrangement, major and minor, macro and micro. What then struck me as an interesting topic to explore was the strange similarity between our experience as global spectators of prison abuse and the experience of abused Abu Ghraib prisoners themselves.

Abu Ghraib used to be a major prison in Saddam Hussein’s regime, dedicated to silencing, torturing, abusing, and eliminating his enemies. Then came the occupation by a coalition led by the U.S. who put the prison complex back to its own use, in the process committing similar acts of silencing, torturing, abusing, and eliminating its enemies. Some tortured prisoners under the occupying forces in fact claimed later that their treatments under the occupying forces at Abu Ghraib were much worse than the treatment they used to receive under Saddam. But this may be only a matter of degrees and kinds.

One obvious difference between the two Abu Ghraibs (before and after the occupation of Iraq) was this: Saddam never seriously claimed to be a human rights advocate and a champion of the cause of exposing and condemning prison abuse and atrocities at home or abroad; the occupying forces did. The significance of the global exposure of images of widespread, especially sexual, abuse and torture at the hands of the champions of “liberty and human rights” cannot be underestimated. The exposure visibly transformed the image of the events underway in Iraq from one involving a confrontation between the forces of liberty and repression to that between two divergent forms of repressive regimes, imperial and domestic. It only served to put the West in the awkward position of having to publicly condemn the atrocities and seek to mend its prison policies under the occupation by institutionally dissociating itself from individual officers, soldiers, and prison guards as “just bad apples” who allegedly committed the abuses on their own.

Tales of prison abuse, of all horrendous though technologically evolving kinds, are as old as the history of empire. Imperial prisons are always prone, more than domestic ones, to “lawless” behavior given their interstitial role in subjugating and punishing foreign subjects lacking rights of due judicial process as citizens of imperial society, especially when they are located (and often tend to be, witness the Guantanamo or Abu Ghraib) on a colonized territory. Nor is the joy of abusing prisoners by captors, or enjoyment of the abuse by others as spectators, new or strange—witness the “barbarian” gladiators, the Coliseum, and the Roman Empire. That the Abu Ghraib abuses were revealed despite the self-righteous posture (vis-à-vis Saddam’s record of torture) and the wishes of the captors, forcing the empire to acknowledge and pretend to making efforts at redressing them, was also not strange, nor unprecedented—witness the public revelations of prison abuse and torture under the U.S.-backed regimes of the Shah in Iran, or of Pinochet in post-Allende Chile.

The strangeness of the Abu Ghraib experience may have less to do with what went on inside the micro confines of the prison, however, and more with the macro global scene. Compare, for instance, the public outrage at the first revelations of the images of abuses, with the rather blasé attitude the public has expressed regarding similar news about abuses rolling in from the U.S. and British controlled prisons. Even the court proceedings of the officers or prison guards accused of abuses were hardly headline news any more by the time they began. Similarly, the first American soldier killed in the war was a headline news for weeks; later the news of the daily deaths did not seems to be as visible and enduring in headlines as they were in the early days of the war. The officially acknowledged lack of sufficient evidence for the claim of the proliferation of “weapons of mass destruction” in Iraq was basically sidelined amid widespread charges that the administration had quashed facts or lied and the majority of the voting population of the technologically most advanced nation in the world effectively put a stamp of approval in the last election on the policies which led to the outbreak of a major pre-emptive war—a war that was rather belatedly declared illegal by the head of the U.N.

“If we had photographs of what our so-called allies in Honduras and El Salvador and Chile were doing, based on training they had received from us in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s,” said Peter Kornbluh of the National Security Archive in Washington, D.C., according to Matthew Rothschild (2004) “the American public would have been even more horrified. … The only difference between this kind of conduct now and in the past is that there wasn’t somebody with a digital camera back then keeping track of what was going on.” According to the Chilean American writer Ariel Dorfman, Rothschild continued to report in his essay “America’s Amnesia” (2004), historical amnesia is “entirely functional to the sort of empire that the United States has become. … It is true that the media does not serve up enough analysis and information to allow people here to judge what is happening. But it is also true that too many people are willingly blinding themselves to truths that are looking at them in the face.”

Strange, indeed, is this global pattern of amnesia that makes atrocities such as those committed in Abu Ghraib possible. What is it that makes us so evasive, forgetful, and subject to such mass amnesia?

II. Theoretical Excursions Onto the Global Prison Yard

The propensity to become habituated to things, ideas, feelings, relations, and processes may be a feature of the human condition, but we have also been endowed with a capacity to critically think and change those conditions and habituations. The sociologist George Simmel (1978) argued that modern society tends to make us numb and blasé toward the fast paced, stimulus overloaded, conditions of life in large metropolitan areas. However, he did not live to see how the same blasé attitude has become a dominating feature of our global cities and public attitudes and policies in the new millennium. Michel Foucault (1977) did emphasize and meticulously trace the origins of the modern carceral society—i.e., society as a lived prison—but he studied the carceral society as a modern historical phenomenon and not as a world-historical reality spanning the rise and fall of political, cultural, and economic empires across historical spacetimes.

Empire is not just a pattern of grand-scale domination and oppression across geographical borders; it is constituted by specific modes of social interaction ritual (Collins 2005; Goffman 1967/1982) taking place at both macro and micro spacetimes. Imperiality is essentially a “relation of ruling” (Smith 1991) of Self by the Other across actual or symbolic borderlands (Anzaldúa 1987). For Anzaldúa, the late Chicana cultural theorist, it is the dualism itself that perpetuates the imperial relation of ruling and carceral everyday experience:

The work of mestiza consciousness is to break down the subject-object duality that keeps her a prisoner and to show in the flesh and through the images in her work how duality is transcended. The answer to the problem between the white race and the colored, between males and females, lies in healing the split that originates in the very foundation of our lives, our culture, our languages, our thoughts. A massive uprooting of dualistic thinking in the individual and collective consciousness is the beginning of a long struggle, but one that could, in our best hopes, bring us to the end of rape, of violence, of war. (Anzaldúa, 1987:80)

Dorothy Smith (1989, 1991) has amply illustrated how, for instance, the imperial relations of ruling operate in the realm of gender dynamics in our academic, curricular, and conceptual worlds. She has noted how “[t]he governing of our kind of society is done in abstract concepts and symbols, and sociology helps create them by transposing the actualities of people’s lives and experience into the conceptual currency with which they can be governed” (Smith 1990:14). One such mode of what Smith calls “conceptual imperialism” (1990:15) is the manner in which the “sociologically constructed world” becomes separated from that of “direct experience” (p. 22), a dualism that parallels the bifurcation of consciousness of career women, and women sociologists, in everyday/night life, enabling the perpetuation of conceptual and experiential imperiality in its gendered forms. For Smith, also, “it is precisely that separation that must be undone” (1990:14). Similarly, for Anzaldúa,

[t]he struggle has always been inner, and is played out in the outer terrains. Awareness of our situation must come before inner changes, which in turn come before changes in society. Nothing happens in the “real” world unless it first happens in the images in our heads. (Anzaldúa 1987:87)

Imperiality practiced across borders is, therefore, only a special case of a general pattern of oppressive relations established between the Self and the Other along class, gender, race/ethnic, communal, age, ability, and other lines of perceived or intentionally fabricated difference. But imperiality can be an intrapersonal process as well, a particular way in which each of us relates to and oppresses her/himself as a person.

Paulo Freire (1970, 1997, 2000) innovatively conceptualized how the imperial mode of pedagogical practice operates as a “banking system” and Foucault (1977) persuasively illustrated how the disciplining of the human subject in modern times has been effectively accommodated through our own self-disciplining facilitated by the guidance and training of so-called specialists and experts of all kinds. As I have argued elsewhere (2004b) for a pedagogy of oppressed and oppressive selves in contrast to perceiving oppression merely in the context of interpersonal and inter-communal relations, imperial oppression does not take place only across bodies, single or collective, but as intrasubjective practices that help perpetuate the imperial order operating on the broader scale. Empire cannot exist without open or subtle forms of inter/intrapersonal imperiality. Under capitalism and modern empire the imperial order is ingeniously veiled under the guise of a “free” market, “free” politics, and an ideology of “freedom.” The class and imperial orders are thereby perpetuated through the agencies of falsely conscious subjects who, believing that they are “free,” in actual terms perpetuate the conditions of their own social incarceration. The prisoner does not even realize he or she is in prison (Gurdjieff 1973).

It is a hallmark of what I call Newtonian sociology to assume that the Self and the Other exist in separate bodies rather than permeating the same body. The Other is not just out there, but also resides in here, within, and what appears to be an Other out there proves upon further reflection to be a part of our self-structure and constitution. When we watch the scenes of Abu Ghraib prison abuses, we are internalizing the imagined selves of both the prison guard and the prisoner, of course with much less (and often devoid of) the emotional intensity of the actual experience. Our detachment from the pain inflicted and experienced, made possible by an artificially detached Self and Other, is not a naturally given fact, but a socially constructed and constituted reality that makes the perpetuation of such atrocities possible in the long run. It is only in the sociological imaginations inspiring motion pictures such as The Green Mile that we can hypothesize what it would be like for a prisoner such as John Coffey to experience the pains of the world as his own intense, unbearable, personal troubles on an everyday basis. That state of empathy we regard as fantasy.

It is such dichotomization of the Self and the Other, via artificially constructed “Islands of Meaning” (Zerubavel 1991), that makes it possible to separate the patient and the doctor, or the student and the teacher, across separate bodies and empower the Other over the Self. Imperiality—that is, the oppressive relations of ruling of the Self by the Other, of which the Abu Ghraib atrocities provided only glaring examples—exist everywhere in our own everyday lives, only in subtler ways. The strangeness of Abu Ghraib did not reside only in what went on inside the prison cells but also in what was taking place in the global prison yard—how we, as a global public, continue to remain numb and blasé toward events and policies that make such atrocities possible. The physical confines and situational dynamics of Abu Ghraib as a microcosm cannot be separated from the symbolic confines and situational dynamics of empire as a strange lived prison within whose belly we live as machines, as sleep-walkers, and as symbolic or actual prisoners.

The Middle Eastern philosopher and mystic, G. I. Gurdjieff (1950, 1973) had already developed by the middle of the last century an elaborate system of ideas and teachings about the human condition, i.e., the existential fragmentation and multiplicity of human organism into separately functioning physical, intellectual, and emotional centers and their associated selves. Gurdjieff’s ideas about the functioning of the human subconscious mind, and what makes it possible for people to live as machines, to say one thing and do another, are yet to be recognized as significant contributions to understanding the functioning of human psyche and by implication of the functioning of small and large scale human organizations (Tamdgidi 2009/12). Perhaps our own habitual academic discourses in the West are at fault for this lack of cross-cultural attention to other contributions to the science of the Self. Gurdjieff’s works in particular, and genuine mystical traditions in general, have had much to say about the human condition as a lived prison, not just symbolically, but in very real terms. However, our Western intellectual traditions, shaped across generations by fragmentations emanating from the modern academic disciplinary boundaries, are yet to recognize that the Buddha in the past and Thich Nhat Hanh (2001) now have been speaking of the same human dilemmas and limitations that are today perpetuating atrocities of imperiality and prison abuse as experienced in Abu Ghraib. Buddha’s reported last words on his deathbed were “Every man is his own prison, but every man can obtain the right to escape. Never stop struggling.”

This is not to deny that Eastern sciences of the self were devoid of shortcomings themselves, especially in taking the larger social structures and dynamics of human societies for granted and attributing human suffering to an existential condition rather than, at least partly, to artificially constructed (and thereby changeable) modes of social production and interaction. However, one may also ask what in our intellectual, academic, disciplinary, and conceptual landscapes prevents us from acknowledging the sameness and potential reciprocal contributions of our scientific achievements across the cultural divides? Are our disciplinary and cultural boundaries also symbolic expressions of the intellectual prison cells we produce and reproduce in our everyday academic lives and publications? What is the nature of this simultaneously macro and micro, long-term and large-scale and everyday in scope, symbolic prison that has confined us as historical actors within the economic, cultural, and political parameters of imperial discourse and practice—not being able to obtain the right to, let alone actually find, a way out? Is there an escape actually possible from this larger prison of indifference, of continuing failed strategies of escape, of this anesthetized living?

A significant anesthetizing factor may be the disillusionment we have inherited and harbored regarding the possibility of liberation altogether, by maintaining conciliatory attitudes toward the status quo, and advancing arguments for the futility of all efforts in favor of escape under the pretext of failed efforts in the past. In his Utopistics, Or Historical Choices of the Twenty-First Century (1998), Immanuel Wallerstein has noted several strategies that have proven to be failures with regards to the transformation of the modern world-system into a non-imperial and more egalitarian reality. The fixation on the seizure of national state power as a strategy for social change is a central factor that he identifies as a self-limiting and ultimately self-defeating strategy on the part of nationalist and socialist forces. But for him the acknowledgment of failures of the past is not a step backward, but one that should propel us forward toward seeking more effective, creative, and substantively rational, strategies in favor of a better world order. He calls this continued search “utopistics”—a simultaneous exercise in science, morality, and politics (Wallerstein 1998; Tamdgidi 2007/9).

Wallerstein’s characterization of state-seizure strategies as being self-defeating is derived from his study of the modern world-system, the first volume of which was published in 1974. The argument is that capitalism has always been a (geographically expanding) world-system since its emergence in the long sixteenth century Europe, and strategies which seek to transform a part of it will inevitably meet the enormous pressures of the system as a whole to return to the systemic status quo in the postrevolutionary period—unless they succeed in translating their local efforts into global transformations. In his other works, however, Wallerstein has also emphasized, drawing on studies of dissipative structures undertaken by the Nobel Laureate Ilya Prigogine (1984, 1997), that at the beginning and ending phases of lives of systems, when crisis and chaos rule and systemic bifurcation ensues, creative actions of relatively small agencies can have significant repercussions for the system as a whole. In other words, the modern capitalist world-economy is most vulnerable today than it has ever been in its lifetime. Yet, agencies of change have in no time been more disillusioned, fragmented, disorganized, and in crisis themselves (Arrighi, Hopkins, and Wallerstein 1988, 1989; Tamdgidi 2001, 2007/9).

III. Derrida on Derrida

The documentary film Derrida (2002), depicting the life of the late French philosopher Jacque Derrida who founded Deconstructionism, begins with his statement that the real future is not one that is predicted and planned and is supposed to come, but one that will take us by surprise:

In general, I try to distinguish between what one calls the future and “l’avenir.” The future is that which—tomorrow, later, next century—will be. There’s a future which is predictable, programmed, scheduled, foreseeable. But there is a future, l’avenir (to come), which refers to someone who comes whose arrival is totally unexpected. For me that is the real future, that which is totally unpredictable. The Other who comes without my being able to anticipate [his or her] arrival. So if there is a real future beyond this other known future, it’s l’avenir in that it’s the coming of the Other when I am completely unable to foresee the arrival. (Derrida)

Contrast this view with that of Wallerstein who, while similarly recognizing the current period of transition as unpredictable and uncertain, does perceive a need to intervene in the chaos that has befallen capitalism in favor of substantively rational outcomes:

… what kind of world do we in fact want; and by what means, or paths, are we most likely to get there? … the first question has usually been asked in terms of utopias, and I wish to address it in terms of utopistics, that is, the serious assessment of historical alternatives, the exercise of our judgment regarding the substantive rationality of possible alternative historical systems. And the second question has been asked in terms of the inevitability of progress, and I wish to present it in terms of the end of certainty, the possibility but the non-inevitability of progress. (1998:65)

Note that in the above, the difference between Wallerstein and Derrida is not in viewing the future as uncertain and unpredictable, but in what, once such uncertainty and non-inevitability are recognized, we may want to do about it. This is perhaps where Wallerstein departs from Derrida, deconstructionism, and the postmodern perspective, as the humanist Edward Said departs from the same in his critique of postmodernism (Said 1994:17):

The purpose of intellectual’s activity is to advance human freedom and knowledge. This is still true, I believe, despite the often repeated charge that “grand narratives of emancipation and enlightenment,” as the contemporary French philosopher Lyotard calls such heroic ambitions associated with the previous “modern” age, are pronounced as no longer having any currency in the era of postmodernism. … For in fact governments still manifestly oppress people, grave miscarriages of justice still occur, the co-optation and inclusion of intellectuals by power can still effectively quieten their voices, and the deviation of intellectuals from their vocation is still very often the case. (Said 1994:17-18)

Perhaps Derrida’s words can be read differently, however, in a way that may point to a meeting of a grandly unpredictable future with a personal possibility of critical thinking and action—one that is reminiscent of the young Marx’s efforts to criticize all that exists (Tamdgidi 2007). So, let us look at this matter more carefully.

Derrida’s deconstructionism is essentially about dehabituating ourselves from modes of seeing, thinking, and feeling that have kept us for millennia in shackles and bounds. Derrida’s emphasis on the unpredictability of the real future is strangely also a recognition of the unbound power of agency. L’avenir is not about what future will come, but about who will come, pointing to the unpredictable nature of the historical subject in being infinitely innovative and creative in forging and making possible new future realities. Despite what may be seen as the agency of an “Other” in Derrida’s vocabulary, further insight may reveal that this Other can best be comprehended and realized through the agency of the self and via self-knowledge, of what Derrida calls “open-ended narcissism.” The Other, in other words, can best be comprehended and make a difference if it is appropriated as a self within. This issue cannot be adequately comprehended without taking into consideration Derrida’s advocacy of deconstructionism. By deconstructing what we take for granted in the world, especially in ourselves, we are in effect making it possible to forge new and unpredictable syntheses and paths into our personal and collective futures. In light of the concerns of this study, in other words, deconstructing Abu Ghraib atrocities as manifestations of the imperial order requires serious efforts at deconstructing the taken-for-granted and habituated imperial relations of ruling constituting the realities of our own everyday, inter- and intrapersonal, lives, activities, and (pre-)occupations.

In another scene in Derrida, this time at the micro level of considerations given to the possibility of human self-knowledge and reflexivity disguised under Derrida’s discourse on Narcissism and Echo, Derrida points out how in the midst of the aging of the body there are elements that remain the same—such as the look of the eyes, or of certain gestures of the hand, that remain as they were in childhood. He states that we ourselves do not easily recognize such continuities in ourselves, while others are in a better position to see and recognize us the way we are. The implication here, of course, may be (if we choose to interpret—and I would say misinterpret—his words as such) that others can better know who we are than we can know ourselves: “These—how do you say—these gestures of the hands, are seen better by the other than myself,” Derrida notes in the film. He expresses the latter in the context of what he calls the question of narcissism. In a scene immediately following the above, Derrida is shown in the presence of a portrait of himself on the wall and of the painter of the portrait standing nearby. Appreciating the painting, he cannot hide his strange feelings of seeing the painting of himself—in effect a look at himself through the eyes of the artist. His words describing his feeling are “anxious,” “worried,” “very strange,” “bizarre,” etc. He appreciates and accepts the gesture of offering his portrait on the wall, but he says “… there are strange things against which one revolts, and others which one accepts. It’s uncanny. It’s bizarre. But I don’t have the desire to destroy it as I often have with other photos or images. It’s a very nice gift she’s given me. She’s given to a little narcissist. An old narcissist [Derrida laughs with amusement].”

In a follow-up scene, however, Derrida is quoted as saying it is not a question of choosing between narcissism and non-narcissism. It is a question of choosing between degrees and kinds of narcissism, ones that are closed to the Other, and those that are “generous, open, extended” to the Other. Note that in simultaneously appropriating and transforming the label “narcissism” by distinguishing between its closed and open kinds, the deconstructionist Derrida is at the same time disarming the critics who have pejoratively used the label to debunk efforts at accommodating seeking self-knowledge as legitimate scholarly practice. Derogatory uses of labels such as “narcissism” and “solipsism,” among others, in other words, cannot be readily dissociated from the academic interaction rituals that exile seeking of personal self-knowledge as a legitimate academic and scientific inquiry. By reappropriating the label and transforming its meaning, Derrida thereby deconstructs a fettering academic and conceptual habitus preventing the pursuit of self-knowledge. In Derrida’s view, what he calls non-narcissism in fact can best be accommodated and fruitful if seen as part of a narcissism that is open, “welcoming and much more hospitable” to the experience of the Other as Other. “I believe that without a movement of narcissistic reappropriation, the relation to the Other will be absolutely destroyed. It would be destroyed in advance. The relation to the Other—even if it remains asymmetrical, open without possible reappropriation—must trace a movement of reappropriation in the image of oneself for love to be possible, for example. Love is narcissistic” (Derrida).

The key here is to note that Derrida is not denying the possibility and the value of personal self-inquiry and self-knowledge; in fact he takes it to heart and sees it as the only way in which an adequate understanding of and relating to the Other may be established. That the Other sees better our hand gestures does not signify that we cannot do so ourselves; that inability is itself a social construction. It may be the case that our habituated ways of knowing, privileging knowing the other and not ourselves, have deprived us from the necessary ways of seeing that would render us as much visible to ourselves as to the Other. Personal self-knowledge, in other words, is not an existential impossibility, but one conditioned and limited by our academic interaction rituals, educational training, and cultural habituations that privilege the Other. Derrida is arguing for a narcissism that is open to the appropriation of the experience of Other, not closed to it. The experience of the Other can best be appropriated via the reappropriation of the Other in the image of oneself, via self-knowledge. To interpret Derrida’s words as a denial of the possibility of self-knowledge is to misappropriate him as an Other, and to misappropriate his knowledge and experience—a misinterpretation which may itself signify the presence of a closed narcissistic attitude.

The denial of the possibility of personal self-knowledge may then itself be deconstructed as a signifier of the presence of imperial relations of ruling—when the Other is empowered and legitimated to represent a person over and above the efforts of the person her/himself. It is no wonder that Derrida finds it difficult to accept to be psychoanalyzed himself—one which essentially legitimates the authority and power of an Other in the person’s effort in attaining self-knowledge:

Interviewer: “Have you ever been in psychoanalysis yourself?” Derrida: “No.” Interviewer: “Would you ever consider it?” Derrida: “No.” (Derrida)

Are we, as sociologists, ourselves enslaved to specific modes of research and pedagogy that eschew the possibility of scientific and liberatory personal self-knowledge within an increasingly global and world-historical framework? Are the ways in which we have defined society and thereby sociology themselves prison walls that have separated and alienated us from other disciplines and cultural traditions that have made concrete advances in the development of theories and practices of personal self-knowledge and transformation?

IV. Newtonian and Quantum Sociological Imaginations

The acts of humiliating the Other, insulting the Other, abusing the Other, raping the Other, when conducted and displayed at the macro levels of imperial prisons, actual or symbolic, are no different from the acts of humiliation, insulting, abusing, and actual or symbolic raping of the Other conceived as both interpersonal and intrapersonal interactions. It is easy to see, notice, and condemn atrocities committed by and on the Other, but because of the ways in which imperial relations of ruling have penetrated and conditioned our epistemologies and sociologies of knowledge—conceptual relations of ruling that overemphasize and legitimize the power of the Other over ourselves—it is much more difficult to see, notice, and resist the strange atrocities we commit against others and ourselves in our own everyday, including academic, lives. If only we could see how empires ridicule, humiliate, and degrade us into submitting to the false images of the good life and happiness that have been imposed on us across millennia, would we be able to realize we are no different from the Abu Ghraib prisoner who was under Saddam, and then under the U.S.-led occupation, subjected to humiliation and physical and spiritual rapes. Our own conceptual and experiential incarcerations outside the prison walls resulting in mass amnesia and evasion, in fact, are what make the perpetuation of those prison atrocities possible.

Escape from this world-historically perpetuated inner and broader imprisonment would then be impossible in the absence of serious and critical efforts at personal self-knowledge within an informed and open, Other-welcoming, sociological framework. This is not to say that the motivation for seeking personal self-knowledge always exists—or that it can be easily and spontaneously attained. The self is not a naturally given and singular, permanent and unchanging, entity waiting to be discovered. The “billiard ball” Newtonian sociologies that have for long shaped our imaginations of the world and ourselves portray the person as a singular entity, and society as relations across persons and separate bodies. According to the Newtonian Laws, bodies are only acted upon and are not self-motivating, self-generating, and self-directing. Newtonian sociologies similarly incarcerate self-knowing and self-motivating actors within the confines of predetermined and law-governed structures.

In contrast, quantum sociological imaginations seek to deconstruct those Newtonian visions and metanarratives of our social psychological landscapes, by revealing the chaotic, multi-selved landscape of our intra- and interpersonal relationships. Newtonian sociologies treat society and thereby sociology in terms of interactions at the atomic level of presumed singular or collective individuals. Quantum sociologies, while recognizing the significance of macro structures, perceive society and sociology in terms of sub-atomic interactions of selves—within or across readily visible bodies. Only by adopting the strange, creative, relational, indeterministic, and open-ended quantum visions of our selves and the world, can we begin to notice the strange imperial relations of ruling that permeate every cell of our inner and outer lives every day and night. Such revelations, as threatening to our egos and our comfort zones as they may be, are prerequisites to introducing open-ended transformations of our lived imperial prisons and colonized selfhoods, inner and outer.

Derrida speaks of his own multiple “I”s in Derrida, while deconstructing the notion of the singular individual as “one:”

In the context of a biography there is this assumption that there is a “one.” And this is a philosophical assumption which has to be questioned. When I say the one, it’s just to avoid the expression such as subject, philosopher, consciousness, ego, person, spirit. But the “one” the biography wants to refer to may be more or less than one. (Derrida)

In the words of P. D. Ouspensky (1949), Gurdjieff was expressing a similar point of view regarding the carceral human condition about and from which he sought knowledge and escape:

“Man has no permanent and unchangeable I. … Man has no individual I. But there are, instead, hundreds and thousands of separate small I’s, very often entirely unknown to one another, never coming into contact, or, on the contrary, hostile to each other, mutually exclusive and incompatible. Each minute, each moment, man is saying or thinking, ‘I.’ And each time his I is different. Just now it was a thought, now it is a desire, now a sensation, now another thought, and so on, endlessly. Man is a plurality. Man’s name is legion.” (59)

In Newtonian sociologies, society is perceived as a set of relations across presumed ‘individuals’ or groups of ‘individuals.’ Quantum sociologies perceive society in terms of a global system of self-relations, permeating both intra-, inter-, and extrapersonal landscapes—in terms of how we relate to ourselves, to one another (in both micro and macro contexts), and to the built/natural environments, respectively. In quantum sociological imaginations there is no difference or separation between the atrocities committed against an anonymous Other tied to prison pipes, and the atrocities committed to us in the imperial lived prison in which we find ourselves. One cannot exist without another. They are two sides of the same reality.

What we watch on the TV screen about atrocities committed against Abu Ghraib prisoners are atrocities committed, simultaneously, across our imperial and colonized selves. It is only our long-inherited psychological buffers that tranquilize and/or prevent our consciences from feeling the pain and the humiliation that the prisoner feels while chained and raped in Abu Ghraib. Our conceptual and emotional inner imprisonments within these inner cells and buffers are as much a part of what makes Abu Ghraib atrocities possible as the policies of occupying forces in Iraq. We cannot escape these more distant or global imperial prisons without reflectively recognizing and overcoming the intrapersonal buffers and walls that help tranquilize our consciences. And this requires, as much as our studies and critiques of globalization, special and specific knowledges, training, and efforts in self-critique and self-examination.

Imperial epistemologies have for long conditioned our thinking to prioritize and favor the Other over the Self. Imperial and carceral psychologies and psychotherapies repeatedly drum in our heads the notion that we are not capable of knowing ourselves and need instead to rely on experts to enlighten us about our own lives. The secret selves we thereby host, selves that may perhaps otherwise be liberating agents of our alternative presents and futures in personal and global spacetimes, therefore, often tremble when confronted with the enormity of the task at hand. They either recede to the remote corners of our carceral inner social cells, or, if they manage to resist, they find themselves in the confines of the selves of others who seek to humiliate, ridicule, or “heal” us into blind submissions—degrading our efforts at seeking prouder selves and worlds. Derrida expresses this chilling irony of our inner lives quite well:

How can an Other see into me, into my most secret self, without my being able to see in there myself and without my being able to see him in me? And if my secret self, that which can only be revealed to the Other, to the holy Other, to God if you wish, is a secret that I will never reflect on, that I will never know or experience, or possess as my own, then what sense is there in saying that it is my secret, or in saying more generally, that a secret belongs, that it is proper to, or belongs to someone, or to some Other who remains some one. It’s perhaps there that we find the secret of secrecy, namely, that it is not a matter of knowing and that it is there for no one. A secret doesn’t belong. It can never be said to be at home or in its place. The question of the self: Who am I? Not in the sense of who am I? But rather who is this I that can say “Who”? What is the I and what becomes of responsibility once the identity of the I trembles in secret? (Derrida)

Above, Derrida is describing not an inescapable human condition, but a lived prison that has conditioned us to never believe that escape is possible. Otherwise, why would we even try to deconstruct our inner and global social imprisonments?

In my reading, deconstructionism is a liberating exercise in breaking apart our conceptual chains, but it itself needs continual deconstruction to highlight the value of constructive approaches to liberatory efforts at theorizing and praxis by example. Paradoxical it is, not to even recognize that “one” is in chain and is in a prison whose walls need to be torn down in favor of building more humane personal and historical alternatives. To abuse and marginalize the selves or “I”s in our personal and collective landscapes who seek freedom is to continue the status quo. Such an “I” obviously would tremble in secret at the “terror of the situation” (Gurdjieff 1950) thus revealed—that one is either a prisoner, or worse, that one is an imperial guard of the carceral society, without or within, disguised as an expert, specialist, and gate-keeper. But then, herein lies the responsibility of the awakening self that, despite the shock received, seeks freedom.

The sociology of self-knowledge as proposed and advanced here has its origins in a critical reexamination and reinvention of Karl Mannheim’s Ideology and Utopia: An Introduction to the Sociology of Knowledge (Mannheim 1936; Tamdgidi 2002). As such it is not an exercise in mere autoethnography, or a purely philosophical preoccupation with the self or the world, but a critical autobiographical research agenda enabling radical and concrete knowledges of the two in favor of a just global society. The problem continues to be framed around a central concern for liberatory theorization and practice, or what Mannheim framed in terms of the search for a science of politics whereby traditional modes of ideological analysis and debunking in political discourse could be transcended in favor of a scientific sociology of knowledge and practice.

Mannheim innovatively posited that the traditional ideological analysis transitions to the sociology of knowledge when intellectual or political adversaries begin to realize that not only the knowledges held by their adversaries, but also those of their own, are socially grounded and thereby biased. His “sociology of knowledge” was therefore meant to pave for a science of politics that would make it possible for political contenders to recognize the limitations and narrowness of their own positions in favor of an alternative, scientific, political discourse that would accommodate the pursuit of a just society beyond the one-sided biases of dominant “ideological” or oppositional “utopian” mentalities. My critique of Mannheim involved a revisitation of the self-defeating conceptual and sociological frameworks that led him to eschew seeking personal self-knowledge as a legitimate scientific and sociological concern, thereby contributing to a blind spot in recognizing his own biases—rendering his otherwise innovative intellectual agenda vulnerable and self-defeating.

The sociology of self-knowledge is, in contrast, concerned with the study of how the investigator’s own self-knowledges and world-historical social structures constitute one another—pursued, as in the Mannheimian version, within a liberatory intellectual framework. As such, it has close affinities with what C. Wright Mills has called “the sociological imagination.” However, it is also different from and goes beyond Mills’s classic formulation. The sociology of self-knowledge aims to extend the sociological imagination in both directions of its dialectical inquiry. On one hand, distinguishing between the study of one’s own and other individuals’ personal troubles, the sociology of self-knowledge takes seriously as part of the investigative endeavor the self-knowledges of the investigator and her or his own personal troubles—that is, on the self-reflective and autobiographical aspect of the microsociological inquiry, seeking to legitimize the seeking of scientific self-knowledge and liberatory autobiographical research and teaching as important sociological interests. It is one thing to study others’ personal troubles, and another to study one’s own. On the other hand, the sociology of self-knowledge seeks to encourage the conduct of scientific autobiographical inquiry in the context of a rigorous and ever expanding knowledge of world-history and long-term and large-scale social structures. The sociologist engaged in the sociology of self-knowledge is specifically interested in how her or his own intimate self-knowledges in everyday life and autobiography on one hand and long-term, large-scale world-historical social structures on the other hand simultaneously intersect and constitute one another.

Another important difference (of emphasis, perhaps) between the sociology of self-knowledge and the sociological imagination is the relaxing of a Newtonian, predeterministic, and somewhat dogmatized assumption built into sociology, the sociology of knowledge, and at least some interpretations of the Millsian sociological imagination. Traditionally, to be “sociological” has involved an effort to explain the micro by the macro, of knowledge by its “social origins,” of inner experience by the “social context,” of the personal troubles by the public issues. The sociology of self-knowledge specifically and intentionally seeks to problematize and deconstruct such predeterministic and dualistic conceptions of the micro and macro, of individual/self and society, etc., pursuing a strategy which takes the interactive nature of the dialectics of self and society seriously in terms of the creative dialectics of part and whole. Social “context,” “origins,” or “issues” do not exist over and above the intra-, inter-, and extrapersonal selfhoods of social actors, especially those of the investigator. Being “sociological” in the pursuit of the sociology of self-knowledge requires adopting what I call a “postdeterminist” attitude toward the dialectics of self and society, subjecting the determination of the nature of part-whole causalities in the self-society interaction to the dynamics of research and social praxis itself.

Another significant contribution of the sociology of self-knowledge is its consciously comparative, cross-cultural, and cross-disciplinary orientations. The sociology of self-knowledge not only recognizes both the limits and the contributions of diverse intellectual traditions in world culture that in one way or another coincide with its own scholarly agenda, but also intentionally seeks to learn from their past experiences of failings and triumphs. It purposely aims to transgress the borderlands of Western utopian, Eastern mystical, and global scientific traditions in thought and/or practice, in favor of seeking new conceptual (methodological, theoretical, and historical), practical, curricular, and inspirational syntheses in pursuit of its scholarly specialization.

If the personal self is conceived as a multiplicity—a relatively autonomous ensemble of intra/inter/extrapersonal social relations that can be self-constituting as much as can constitute and be constituted by world-historical social structures—it necessarily follows that the person her/himself must be empowered and recognized as potentially the best, and ultimately the only, authentic source for the development of scientific knowledge about her or his own selves in a global and world-historical context. The sociology of self-knowledge aims to advance and invent new conceptual and curricular structures for the pursuit of the above goal. It was toward this end that Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge (2002-), a publication of OKCIR: The Omar Khayyam Center for Integrative Research in Utopia, Mysticism, and Science (Utopystics), was launched for the purpose of conduct, collection, and publication of teaching and research work in the field within a theoretically and pedagogically creative and libratory framework.

V. Conclusion: Empire as a Lived Prison

There is no doubt in my mind that the expert occupational therapist meant well in helping to heal my hand and offering to make me the clinic’s poster child. It is with the expectation of a power of healing entrusted to the occupational therapist as an expert that I went to her and put my hand in her hands for healing.

However, she, as an “Other,” separately embodied, did not and could not feel what I felt about the analogy of her offer and of the atrocities at Abu Ghraib. She was not as open and Other-welcoming as I tried to be toward the connection of her advertising proposal with the realities of the Middle Eastern and global scenes. She did not recognize the gaze of bewilderment and amusement in my eyes, nor the gestures in my hands and head; nor did she recognize the irony regarding the similarity between my wired hands and those of the Abu Ghraib prisoner standing on the shaky cardboard box. Only I, being open to what I was hearing from her and to what was happening in another part of the world, could experience in secret the irony in my body while I was lending my hand to her for healing.

Her original lack of empathy and my own experience were not naturally given conditions. There is no reason why it had to be this way; alternative experiences of learning and cultural upbringing may have caused a circumstance where one party did feel (and not be alienated from) what the other was feeling. I was, on my part, a prisoner of assuming that her expertise could heal my hand. She made a good effort, and received good compensation for her service, but my hand still remained aching and in many ways got worse. Interventions, painfully, of other specialists since then—including an acupuncturist, a neurologist, a hand surgeon, and chiropractors whom I consulted later—also have not proven helpful. Ultimately, I was the one who decided to seek the help of others, and perhaps ultimately I will find some healing.

It would of course be threatening to my occupational therapist to know that her healing powers were limited. But the fact also remains that being confronted with my response, as Derrida would put it, her “I” trembled. The question is, was her narcissism of the closed or open kind? Was this trembling a beginning of spiritual or multicultural awakening regarding issues of difference? Did she now become open to how I and other Middle-Eastern-looking men or women feel and think, especially in the post-9/11 era characterized by an unprecedented rise of Islamophobia? Would she deconstruct her own selves and life as much as she may pretend to know about my keyboarding habits? Or was the experience for her a momentary awakening followed by a relapse into the anesthetized feeling of self-importance, and a return to the comfort zone of an expert’s role licensed by a carceral society, to being amused that I, after all, looked also like a Latin American?

The lessons of the Abu Ghraib scandal similarly continue to evade those needing them, despite having increasingly drawn the critical attention of scholars. Noting in their article in Social Forces that the “outrage over revelations of torture and abuse has faded from public discourse, but a number of questions remain unanswered,” Hooks and Mosher called “on sociologists to become involved in the study of torture and prisoner abuse” (2005:1627). Their study concluded that the abuses were not incidental but systemic in nature, arising from official rationalizations of a policy bent on dehumanization of the enemy to pursue a “War on Terror.” Kersten and Mohammed have also argued that the abuses were results not of poor crisis management, but of “systemic neurosis at the highest levels of government” (2005:471). In “Campaign Posturing, Military Decision Making, and Administrative Amnesias” (2005), Hedges and Hasian Jr. similarly explored the “amnesias associated with prior presidential positions on torture, which is believed to be one key thread in the selective tapestry of political arguments that appeared during the 2004 U.S. elections” (694). Following a different line of inquiry and drawing parallels with Theodore Adorno’s “Education After Auschwitz,” Henry A Giroux, in his article “Education after Abu Ghraib” (2004) explored “not only how the photographs of abuse and torture signaled a particular form of public pedagogy, but also how pedagogy itself becomes central to understanding the changing political, ideological, and economic conditions that made the abuse at Abu Ghraib possible …” (779).

Much time has transpired since the photographic revelations of prisoner abuse by U.S. prison guards at Abu Ghraib, preoccupied with breaking into pieces their prisoners’ bodies, spirits, and dignity by resorting to every humiliation un/imaginable. But Omar Khayyam’s quatrain opening this article seems strangely telling in this context. The empire itself, and not just its war policies and strategies, continues to shatter by an otherwise predictable lack of success in pursuing its goals, then in Iraq and still in Afghanistan. The question remains, will the necessary lessons be learned to prevent further atrocities?

Empires and Saddams (or Bin-Ladins) are two faces of the same coin. The West sees itself as a beauty, desperately seeking to cleanse the faces of the beast on the wall of the East, not realizing that the wall is a mirror, and the beast’s reflections by-products of its own colonial adventures across world-historical spacetime. Abu Ghraib does not signify the strangeness of a local imperial prison in the here and now; it also expresses the strangeness of an horrendously disgraceful imperial metanarrative still telling and shaping world-history.

Abu Ghraib is the strangely lived experience of empire in which we choose to remain abused prisoners of our own social constructs, at a world-historical juncture when conditions for transcending such a state are realistically possible. What is truly strange is how we, the ever globalizing audience witnessing such abuses, continue to stand on the shaky cardboard boxes of rising and falling empires, with hoods of amnesia and evasion put on our minds, and increasingly sophisticated media wires of true or false fears manipulating our emotions.

To escape, the mystic said, one must first realize one is in prison.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this chapter had been previously presented on a panel titled “Iraqi and Afghani Prisons: Social Scientific Theories of Situational Dynamics of Prison Life in Light of the Atrocities Committed” at the 75th Annual Meeting of the Eastern Sociological Society (theme “Sociology and Public Policy”), held in Washington, DC, in March 2005.

References

Adorno, T. W. 1998 ‘Education after Auschwitz.’ Pp. 191-204. in Critical Models: Interventions and Catchwords, T. W. Adorno. Columbia University Press, New York.

Amann, Diane Marie. 2005. “Abu Ghraib.” University of Pennsylvania Law Review 153::2085-2141.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1987. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, San Francisco: aunt lute books.

Arrighi, Giovanni, Terence K., Hopkins and Immanuel Wallerstein 1989. Antisystemic Movements. London and New York: Verso.

Arrighi, Giovanni, Terence K., Hopkins and Immanuel Wallerstein 1992. “1989, The Continuation of 1968,” Review XV:221-242.

Associated Press. 2006. “White House Shelved Iraqi Trailers Report.” April 12.

Balestrieri, Elizabeth Brownell. 2004. “Abu Ghraib Prison Abuse and the Rule of Law.” International Journal on World Peace 21, 4:3-20.

Bishop, Donald H. 1995. Mysticism and the Mystical Experience: East and West. London and Toronto: Susquehanna University Press.

Bourke, Joanna. 2005. “Sexy Snaps.” Index on Censorship, 34, 1:39-45.

Brown, Michelle. 2005. “Setting the Conditions” for Abu Ghraib: The Prison Nation Abroad.” American Quarterly 57:973-997.

CNN News. May 4, 2006. “Hecklers Disript Rumsfeld Speech.”

Cohen, Stanley. 2005. “Post-Moral Torture: From Guantanomo to Abu Ghraib.” Index on Censorship 34, 1:24-30.

Collins, Randall. 1998. The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Collins, Randall. 2005. Interaction Ritual Chains. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Daniel, Douglass K. 2006. “Murtha: New Scandal Worse Than Abu Ghraib.” Associated Press, May 28.

Deikman, Arthur J. 1982. The Observing Self: Mysticism and Psychotherapy. Boston: Beacon Press.

Derrida. 2002. Dir. Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering Kofman. Prod. Jane Doe Films. New York: Zeitgeist Films. DVD.

Fattah, Hassan M. 2006. “Symbol of Abu Ghraib Seeks to Spare Others His Nightmare,” New York Times, March 11.

Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Pantheon.

Freire, Paulo. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos. New York: The Seabury Press, A Continuum Book.

Freire, Paulo, Ana Maria Araujo Freire, and Donaldo Macedo. 2000. Paulo Freire Reader. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group.

Freire, Paulo, and Donaldo Macedo. 1997. Teachers as Cultural Workers: Letters to Those Who Dare Teach. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

Goffman, Erving. 1967/1982. Interaction Ritual. New York: Pantheon (originally published by Doubleday & Co., Inc.)

Giroux, Henry A. 2004. “Education After Abu Ghraib: Revisiting Adorno’s Politics of Education.” Cultural Studies 18:779-815.

Greer, Edward. 2004. “”We Don’t Torture People in America”: Coercive Interrogation in the Global Village.” New Political Science 26:71-387.

Gurdjieff, G. I. 1950. All and Everything: Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson. First Edition. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Gurdjieff, G. I. 1973. Views from the Real World. New York: Arkana.

Hanegraaff, Wouter. 2005. Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism. Amsterdam: Brill Academic Publishers.

Hanh, Tich Nhat, 2001. Essential Writings. New York: Orbis Books.

Hanley, Charles J. 2006. “Ex-WMD Inspector: Politics Quashed Facts.” Associated Press, May 13.

Hersh, Seymour M. 2004 “Torture at Abu Ghraib,” The New Yorker 10 May, 42-7.

Hoffman, Paul. 2004. “Human Rights and Terrorism.” Human Rights Quarterly 26:932-955

Hooks, Gregory and Clayton Mosher. 2005. “Outrages Against Personal Dignity: Rationalizing Abuse and Torture in the War on Terror.” Social Forces 83:1627-1646.

BBC News. 2004. “Iraq War Illegal, Says Annan” September 16.

Hedges, James and Marouf Hasian Jr. 2005. “Campaign Posturing, Military Decision Making, and Administrative Amnesias.” Rhetoric & Public Affairs 8:694-698.

Kear, Adrian. 2005. “The Anxiety of the Image.” Parallax,11, 3:107-116.

Kersten, Astrid, and Sidky Mohammed. 2005. “Re-aligning Rationality: Crisis Management and Prisoner Abuses in Iraq.” Public Relations Review, 31:471-478.

Linfield, Susie. 2005. “The Dance of Civilizations: The West, the East, and Abu Ghraib.” Dissent 52, 1:46-54.

MacMaster, Neil. 2004. “Torture: from Algiers to Abu Ghraib.” Race & Class 46, 2:1-21.

Needleman, Jacob. 1993. “G. I. Gurdjieff and His School.” Pp. 359-380 in Modern Esoteric Spirituality (part of the series World Spirituality: An Encyclopedic History of the Religious Quest) edited by Antoine Faivre and Jacob Needleman. London: SCM Press Ltd.

Needleman, Jacob. 1996. “Introduction.” In Gurdjieff: Essays and Reflections on the Man and his Teaching, edited by Jacob Needleman and George Baker. New York: Continuum.

Ouspensky, P. D. 1949. In Search of the Miraculous: Fragments of an Unknown Teaching. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Publishers.

Pickler, Nedra. 2006. “Report Raises New Questions on Bush, WMDs.” Associated Press, April 12.

Prigogine, Ilya. 1984. Order Out of Chaos. Reissue edition. New Jersey: Bantam.

Prigogine, Ilya. 1997. The End of Certainty: Time, Chaos, and the New Laws of Nature. New York: Free Press.

Razack, Sherene H. 2005. “From Peacekeeping Violence in Somalia to Prisoner Abuse at Abu Ghraib: The Centrality of Racism.” Global Dialogue 7, 1/2:134-141.

Rich, Frank. 2005. “On Television, Torture Takes a Holiday.” New York Times Jan. 23. 154, 53103, section 2, pp. 1-17.

Rockmore, Tom. 2005. “The Scandal of Abu Ghraib.” Peace Review 17, 2/3:307-314.

Roth, Kenneth. 2005. “Getting Away with Torture.” Global Governance 11:389-406.

Rothschild, Matthew. 2004. “America’s Amnesia.” The Progressive. July.

Said, Edward W. 1994. Representations of the Intellectual. New York: Vintage Books.

Schmitt, Eric. 2005. “4 Top Officers Cleared by Army in Prison Abuses.” New York Times, April 23. 154, 53193, pp. A1-A5.

Simmel, Georg. 1978. The Sociology of Georg Simmel. Translated and edited by Kurt H. Wolff. New York: The Free Press.

Solomon, Norman. 2004. “The Coming Backlash Against the Outrage.” Fair: Fairness & Accuracy In Reporting.” May 13.

Smith, Dorothy. 1989. The Everyday World As Problematic: A Feminist Sociology. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Smith, Dorothy. 1990. The Conceptual Practices of Power: A Feminist Sociology of Knowledge. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Tamdgidi, Mohammad H. 2001. “Open the Antisystemic Movements: The Book, the Concept, and the Reality.” Review (Journal of the Fernand Braudel Center) XXIV:299-336.

Tamdgidi, Mohammad H. 2002-. Human Architecture; Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge. Volumes I, II, and III. ISSN: 1540-5699. (For table of contents of the five issues already published, please visit http://www.okcir.com. All articles abstrated in CSA Illumina’s Sociological Abstracts, and are forthcoming (with full-text) in EBSCO’s SocINDEX.)

Tamdgidi, M. H. 2002a. “Ideology and Utopia in Mannheim: Towards the Sociology of Self Knowledge.” Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge I, 1:120-140.

Tamdgidi, Mohammad-Hossein. 2002b. “Mysticism and Utopia: Towards the Sociology of Self- Knowledge and Human Architecture (A Study in Marx, Gurdjieff, and Mannheim),” Ph.D. Dissertation. SUNY-Binghamton.

Tamdgidi, M. H. (Behrooz) 2004a. “Rethinking Sociology: Self, Knowledge, Practice, and Dialectics in Transitions to Quantum Social Science.” The Discourse of Sociological Practice 6, 1:61-81.

Tamdgidi, Mohammad. 2004b. “Freire Meets Gurdjieff and Rumi: Toward the Pedagogy of the Oppressed and Oppressive Selves.” The Discourse of Sociological Practice 6, 2:165-185.

Tamdgidi, Mohammad H. Forthcoming a (2006). “Toward a Dialectical Conception of Imperiality: The Transitory (Heuristic) Nature of the Primacy of Analyses of Economies in World-Historical Social Science.” Review (Journal of the Fernand Braudel) XXIX, 3.

Tamdgidi, Mohammad H. Forthcoming b (2006). “Middle Eastern Insights into Anzaldúa’s Utopystic and Quantum Sociological Imagination: Toward New Agenda.” Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, Special Issue, Summer.

Tamdgidi, Mohammad H. Forthcoming c (2007). Advancing Utopistics: The Three Component Parts and Errors of Marxism. Boulder, Colorado: Paradigm Publishers.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. l974. The Modern World-System, I: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century. New York & London: Academic Press.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1998. Utopistics Or, Historical Choices of the Twenty-First Century. New York: The New Press.

Wikipedia. “Abu Ghraib.”

Zernike, Kate. 2005. “Behind Failed Abu Ghraib Plea, A Tale of Breakups and Betrayal.” New York Times May 10. 154, 53210, pp. A1-A13.

Zerubavel, Eviatar. 1991. The Fine Line: Making Distinctions in Everyday Life. New York: Free Press.