Editor’s Note: To Be of But Not in the University

$15.00

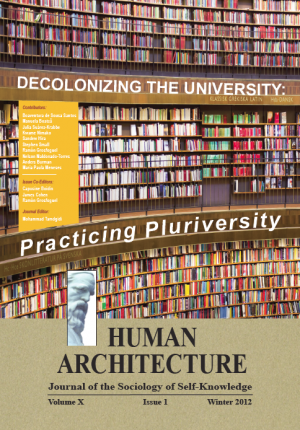

This is the journal editor’s note to the winter 2012 issue of Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, entitled “Decolonizing the University, Practicing Pluriversity,” including papers that were presented at the conference entitled “Quelles universités et quels universalismes demain en Europe? un dialogue avec les Amériques” (“Which University and Universalism for Europe Tomorrow? A Dialogue with the Americas”) organized by the Institute des Hautes d’Etudes de l’Amerique Latine (IHEAL) with the support of the Université de Cergy-Pontoise and the Maison des Science de l’Homme (MSH) in Paris on June 10-11, 2010.

Description

Abstract

This is the journal editor’s note to the winter 2012 issue of Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, entitled “Decolonizing the University, Practicing Pluriversity,” including papers that were presented at the conference entitled “Quelles universités et quels universalismes demain en Europe? un dialogue avec les Amériques” (“Which University and Universalism for Europe Tomorrow? A Dialogue with the Americas”) organized by the Institute des Hautes d’Etudes de l’Amerique Latine (IHEAL) with the support of the Université de Cergy-Pontoise and the Maison des Science de l’Homme (MSH) in Paris on June 1011, 2010.

Addressing the significant themes and findings of the studies included in the proceedings, the editor asks whether it is possible to decolonize the Westernized university solely from within its existing structures and through the agency of its own critical, yet still vested, actors. Is the European, as well as broader Westernized global, university system confronted with a binary crossroads, or can the posing of the problem as such in terms of a duality, at the expense of exclusion of alternative efforts outside the Westernized university, be itself a factor in determining the outcome of the journey?

The editor argues that based on his own experience, it would be self-defeating to depend solely on the agencies operating within the carceral structures of existing university systems to seek a way out in favor of utopystic outcomes.

As Anders Burman argues in the collection, and does so drawing on non-Western ways of knowing, the way one thinks (and thereby seeks solutions) is intricately and organically dependent on the place one thinks with—and this should necessarily include the Westernized university itself—including its dominant epistemic standpoints, disciplinary structures, organizational frameworks, and procedures.

The editor concludes with a brief comment on his recent decision, partly inspired by the works in this collection itself, to retire early in the near future from his tenured university position in favor of more autonomous and utopystic, pluriversal outcomes.

Editor’s Note: To Be of But Not in the University

I know I have reversed for the purpose of formulating the title of this editor’s note, the usual expression of the adage “being in but not of the world.” But the reverse expression is exactly what I mean to use as a window to what I am about to argue in this editor’s note.

Capucine Boidin, James Cohen and Ramón Grosfoguel, as the co-editors of this, Winter 2012 issue of Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, who also served as co-organizers of the conference of which this is a proceeding—namely, the conference entitled Quelles universités et quels universalismes demain en Europe? un dialogue avec les Amériques (Which University and Universalism for Europe Tomorrow? A Dialogue with the Americas) organized by the Institute des Hautes d’Etudes de l’Amerique Latine (IHEAL) with the support of the Université de Cergy-Pontoise and the Maison des Science de l’Homme (MSH) in Paris on June 10-11, 2010—have eloquently summarized the contribution of each article to the volume.

So, I will not summarize them here as such again, but only to the extent each contributes in shedding light on one or another aspect of my own reading and appreciation of the authors’ works—including the co-editors’ own reading of them.

I think that implicit in the central theme shared by all the contributions in the volume is not simply the question of what is wrong with the existing Westernized global university system; nor is it that of imagining what an alternative pluriversity may be like—even though the latter is not a direct focus of the collection in itself. The most significant question and challenge that arises from the pursuit of studies undertaken for the conference and shared in this proceeding is how to arrive at the latter despite the conditions and obstacles posed by the former.

In their introduction, the co-editors express the above in terms of asking what it could mean to “decolonize the university and its Eurocentric knowledge structures” (p. 1). And, therefore, it is important to consider the contribution of each author in terms of this overall purpose for the conference and the collection as a whole, so that the limited focus of one or another author on one or another aspect of the inquiry would not be judged in terms of the author’s lack of attention to the complexity of the inquiry as a whole.

Reflecting on the authors’ contributions herein, the co-editors argue that the crisis of the Westernized university today is not simply contextual—having to do with “not only class exploitation but also processes of racial, gender, and sexual dehumanization” (p.2) characterizing the world-system of which it is a part. It is also a crisis of its own hitherto dominant “academic model” based on the presumption of a Eurocentric epistemic canon that attributes truth only to the Western way of knowledge production at the expense of disregarding “other” epistemic traditions.

So, when the alternative “pluri”-versity is posed as the destination of the process of decolonization of the present “uni”-versity, the latter should be seen not merely in terms of an applicative “pluriversity” of an otherwise “universally” presumed Eurocentric epistemic model (such as, for instance, the functionalist conception of the university in terms of a “plurality” of academic and industrial interests and actors in running the increasingly privatized models of academic capitalism seen in progress today1In their work, Global Citizenship and the University: Advancing Social Life and Relations in an Interdependent World (Stanford University Press, 2011), for instance, Robert A. Rhodes and Katalin Szelényi make this point clear by stating: “After all, pluriversity knowledge can be applied in a variety of ways, be that for humanitarian or mercantile purposes” (p. 108). In other words, there can be more accommodative versus more radical and pathbreaking approaches to practicing pluriversity. This is obvious, since pluriversity in and of itself basically highlights the pluralist character of knowledge production in an institution, even at the epistemic level, and does not necessarily indicate whether or not a particular, open versus closed, model is predominant in guiding the knowledge production process.

The co-editors acknowledge that criticisms of the dominant Eurocentric academic model have not only been present within the academia itself, but have steadily grown, with some successes in establishing alternative organizational conduits within the academia in order to pursue alternative, critically pluriversal models of knowledge production and practice. In fact, the authors contributing to this volume are themselves lucid representations of such alternative thinking and practice, more or less anchored within academia itself.

Building on the findings of the contributors, then, the co-editors highlight the value of the move among critical thinkers and academics to embrace alternative conceptual models, such as Enrique Dussel’s notion of “transmodernity” or Boaventura de Sousa Santos’ notion of “ecology of knowledges,” and of “pluriversity” indeed, in terms of what an alternative vision of a process of knowledge production that is open to epistemic diversity could be. Such alternatives do not necessarily abandon the notion of universal knowledge for humanity, but embrace it via a horizontal strategy of openness to dialogue among thecontributions made by all different intellectual and epistemic traditions in the world.

The key here, then, is to appreciate what the authors in the volume have contributed toward understanding what the co-editors call the “initiatives to fight epistemic coloniality” (p. 3) as steps toward moving from the “university” to the “pluriversity” models of academic knowledge production and practice.

Boaventura de Sousa Santos offers an excellent and visionary synopsis, in the form of twelve “strong questions,” of the challenges facing the European, and indeed all Westernized, universities, his answers also giving a creative sense of what a pluriversity could be. However, the question as to how and through what agencies the alternative path and vision may be chosen over the ones maintaining the status quo is not an explicit concern of his contribution.

Santos does raise the spectre of whether the university as we know it has a future, and does recognize the fact that the university as we know it may be becoming just one, among many, alternatives for the production of knowledge, and in doing so opens up both conceptual and practical spaces for new and creative experimentations in favor of his liberatory vision of academia.

However, what the challenges may lie in choosing one strategy over the other (reform from within the university system versus experimenting with models outside the university structure) remains to be explored in terms of their effectiveness as contrasting as well as combined strategies in achieving the alternative vision of academia as a pluriversity.

Several of the other insightful studies published in the volume provide excellent illustrations of the challenges facing the “transition” efforts. Manuela Boatcã’s study of German universities and the revival of area studies points to what seems to be efforts in recycling “re-Westernized” models molded after the US university systems begun decades ago, ones that have already been challenged in terms of the way they serve the imperial academic discourse and policy making.

It is true that for those of us having to live within the university system, the new discourse may offer new spaces in turn for critical studies of gender and minority politics; however, the challenge does not seem to be any less than what critical academics have already faced in the US.

The study by Julia Suárez-Krabbe of the Danish university and her advocacy and pursuit of introducing alternative and critical theories and perspectives “from within” the university structure amid an otherwise mainstream academic context shaped by neoliberal university reforms at the same time contrasts and complements the strategies cited by Kwame Nimako and Sandew Hira in the context of Dutch university system where the emphasis of resisting hegemonic, imperial models of academic practice, shifted to critiques by “minority groups” organizing their efforts and voices from outside the university structure. Their studies both illustrate the extent to which the ideological structures of Eurocentrism and Western racist epistemologies belittling other traditions is deeply entrenched in the very ideological structure of slavery and abolition studies.

The insightful studies by Stephen Small, Ramón Grosfoguel, and Nelson Maldonaldo-Torres in the context of the US academic system and that of Maria Paula Meneses in the context of Portugal’s colonial history in Mozambique, highlight the continued challenges facing critical academic studies such as ethnic studies and studies of race and colonial memory and the extent to which, as Grosfoguel puts it, disciplinary colonization and liberal multiculturalism from without and identitarian politics from within the critical academic movement continue to pose significant challenges to the radical transformation and transition of the Westernized university in favor of pluriversal academic outcomes.

In the context of the above, the study by Anders Burman stands out as one that challenges the critical challengers of the academic system to think again about what it really means to decolonize Western epistemic thinking and practices in favor of liberatory outcomes. For this reason, it is worth dwelling in more detail on Burman’s study, and recalling the ways of knowing he so eloquently reports from his indigenous activist and shaman interviewees’ accounts in Bolivia.

I do not wish to oversimplify and summarize further the rich contributions made by authors noted above, and that of Burman below—they deserve to be read carefully on their own of course. However, Burman asks questions that problematize the very way we ask questions in our critique of what we regard as Western, Eurocentric, epistemology.

Having drawn on the implication of what he has heard from his Bolivian interviewees regarding the true nature of knowledge as one that goes beyond mere thought-knowledge and one that should involve feelings, the body, and the very places in and with which one thinks and feels, Burman asks:

Here I pose a question: if books and lectures are basically about the opinions of specific individuals and proper knowledge is to be gained only in the experiential, non-linguistic, inter-relational dealings with and in the world, is there not a risk that a project aimed at decolonizing knowledge and decolonizing the university precisely by way of books and lectures—i.e., in a logocentric, or as I would suggest, a ‘librocentric’ project of decolonization—ends up reproducing the colonial epistemological asymmetries of knowledge production? (p. 103)

Burman further adds:

There is, then, nothing esoteric about ‘thinking with places’; it is rather a way to produce knowledge from beyond Cartesian dichotomies such as nature-culture and object-subject and from beyond the hegemony of logocentric and librocentric epistemologies. (p. 109)

Complicating the picture and the implication this may have for pursuing “pluriversal” strategies that would bring the indigenous discourses—one must add here as well the critical academic discourses in the Westernized university— in dialogue with the mainstream academic models in institutional contexts and “places” dominated by hegemonic Eurocentric discourses, Burman further asks:

Above, I argued that there is always a risk in using hegemonic academic language and theories since they may impede us from seeing beyond the epistemological and ontological presuppositions of colonial modernity. I also argued that the academic curriculum is to a certain extent still conventional even at indigenous universities. The solution to this, then, would seem to be to decolonize the curriculum by transforming its content so that indigenous traditions of knowledge and thought could be taught more comprehensively in the lecture halls. Nevertheless, and here I identify a second risk, if indigenous knowledge is integrated into the university it may result that instead of decolonizing the university we end up colonizing indigenous knowledge. (p. 116)

The significance of this line of inquiry and warning must be evident when advocating transitions from the university to pluriversity in institutional contexts that are still deeply structured after what Grosfoguel calls “Eurocentric fundamentalism.” What if, following Burman’s warning, we realize that the very efforts one is making within the contextual and institutional parameters of Westernized university contributes to the very flattening and distortion of the indigenous and alternative epistemologies we seek to internalize (or newly create) within the belly of the university system?

Would the discourses on and seeking after “pluriversity” and seeming incorporation of them in the belly of the mainstream Westernized university actually end up dulling and distorting their epistemic and cosmological innovativeness, helping entrap them in a carceral university environment where the very specialists in critical academic discourse become agents for advancement of what Herbert Marcuse called a one-dimensional man/society (and one must add here, university)—in which the very process of critical and “indigenous” thinking becomes sublimated and distorted in the conceptual trappings of Western epistemic discourse and commodified and passed on as alternative, pluriversal, knowledge?

Burman asks again:

If the decolonization of knowledge primarily turns out to be a question of ‘critical’ intellectual theorizing; if it is fundamentally about books, lectures and words; if indigenous epistemologies are disregarded or simply ignored in the very practice that expressly aims at doing away with the epistemological disequilibrium of the present colonial world-order—is there not a risk that the ‘decolonization project’ ends up buttressing epistemological asymmetries instead of under- mining and challenging them? Is there not a risk that the decolonization of knowledge be converted into a project of urbane scholars and intellectuals, a project of Academia, a logocentric, librocentric project? (Burman, p. 114)

The carceral trappings of Western epistemic systems bundled amid all kinds of university positions and promotions, rewards, and assessments—especially for those critical thinkers still reluctantly vested in the Westernized university—is great, and if Burman’s Bolivian shaman or activist teachers are right, quite elusive.

At the very time we are expounding these critiques and counter-critiques, we may be becoming more entrapped in the very structures which we seek to transcend. As another teacher from a different spiritual tradition used to say, for one to set oneself free, one must first realize that one is in prison.

• • •

It may seem paradoxical—but no longer is so to me—that I did not appreciate the findings of Burman as much as they deserved until, for other reasons not directly related to this volume’s publication, I decided recently to retire early from my tenured university position in pursuit of long-postponed projects. Burman’s shaman teacher Don Carlos’s teaching regarding “thinking with a place” is quite relevant here.

I remember that about 10 years ago, when concluding my dissertation research as a comparative study of utopian, mystical, and social scientific/academic thinking as represented in the teachings of Karl Marx, G. I. Gurdjieff, and Karl Mannheim, I confronted a three-fold crossroad.

My theoretical inquiry into the causes of failure of hitherto efforts in these world-historical traditions in building a just global society had led to the insight that the failure has much to do with the historical separation of these world-historical traditions themselves from one another and, substantively reflected in their associated dualistic liberatory strategies that one-sidedly focused on the self versus the social dimension of liberatory transformation.

In order to transcend such historical and substantive distanciations across the three world traditions, however, I was confronted with the dilemma of organizational affiliation with one or another historical movement. At the time, even though I was convinced—based on prior experience—that maintaining organization independence and distance with respect to utopian and mystical traditions were necessary (more concretely, in terms of involvement in specific political and spiritual organizations), I was led to believe, with some hesitation, that perhaps as a member of the university faculty and academia, I would be able to pursue my interests in bringing about a constructive and fruitful scholarly dialogue across the three intellectual traditions.

In the meantime, however, I also decided that maintaining some institutional distance and autonomy from academia was crucial and this conviction manifested itself in the launching and continued publication of this journal and the vision of a research center of which it is a part. For those interested, they can read further regarding this background by consulting the editorial perspective of Human Architecture, and the description of the research center which inspires its publication—Okcir: The Omar Khayyam Center for Integrative Research in Utopia, Mysticism and Science) available both in print and online (www.okcir.com).

The experience of my full-time involvement in academia since 2001, leading to and beyond the granting of tenure, however, increasingly and continually confronted me with the question I posed to myself ten years ago. The details are not necessary here, though some may be found in the brief editorial notes of various issues of the journal, in particular those of the issues of volume IX published in 2011. However, Burman’s teacher don Carlos put it well when he said that thinking always takes place with a place, and not just merely with books and publications:

“You still don’t get it, do you? I can’t pass anything on to anyone. They have to sense it for themselves. I can only point to the places they should go… then they will go there and feel and think. If it’s a good place, they will think good thoughts.” (don Carlos, as quoted in Burman, p. 111)

However, there are also other ajayus. There are harmful ajayus that make people step out of the flow of life and enter other flows where there is no reciprocity. There are ‘strange’ ajayus that cause disorder, illness and even death. (Burman, p. 109)

Yes, it could not be expressed better, and I have faced my share of ajayus in the academia. The past ten years have supplied me with a plenty of experiential knowledge to conclude now that, at least for me, it is simply impossible to pursue my project while being embedded in a formal academic setting no matter how progressive the overall university leadership and many faculty at the university may be.

There is no question that each university must be considered and judged based on concrete analysis of its specific situation. I have certainly benefitted from the academic institutions of which I have been a member in the past several years while benefitting them as well—and acknowledgment of this reciprocity is important.

However, it is now clear to me that participation in academic organization and life is intricately implicated, as part of a larger social context which it serves, in maintaining structures that not only advance a particular, Eurocentric epistemic agenda, but also emasculate the pluriversal traditions and voices that are reluctantly accepted in their midst.

This is not to say that all actors in the university are equally implicated and consciously pursuing such an agenda. On the contrary, the brilliance of such a socially constructed structure lies in the fact that it continually reproduces itself despite its continual accommodation of critical voices into itself—ones that are clearly set out with more or less good intentions.

As we lay before us this publication pursuing a discourse on how to move from the university to practicing pluriversity, Burman’s words below prove to be chilling—to the extent that one awakens to the nature of Westernized university, the one-dimensional society of which it is an integral part (and in fact a reproducer), and the extent and depth of the problem at hand:

A few adjustments in our academic curriculums or in our lists of references are not sufficient to bring about political, theoretical, epistemological and, in the end, existential and cosmological paradigmatic revolts. We would still be reproducing the colonial images and ‘truths’ that the hegemonic categories of thought reduce the world to. To learn to think in and with other categories is a good start, but other categories will not make our ontological pillars shiver. For that to happen, other experiences are necessary. In other words, there is no way we are going to intellectually reason our way out of coloniality, in any conventional academic sense. There is no way we are going to publish our way out of modernity. There is no way we are going to read our way out of epistemological hegemony. (p. 117)

• • •

To conclude this editorial note, let me share with you a story the late Jesse Reichek (1916-2005), a dear undergraduate advisor of mine and a noted painter and “Professor of Design” at U.C. Berkeley, shared with me once—one that can give the reader a hint about his unusual teaching and advising style as well.

There is much learning material in this anecdote, which he shared with me when I was about to receive my doctorate (he also served as an external examiner on my dissertation committee). At the time, I had completed my dissertation but was not sure of depositing it, getting my degree “paper,” and moving on to an academic career.

This was at a time when, as briefly related above, I doubted whether joining the academia would divert me from the path I had envisioned to take as a conclusion of my doctoral studies. Recalling this story now, I find that it has a new meaning and significance for me today.

At that time, hearing my doubts about an academic degree and career, Reichek asked during one of our long phone conversations: “Did I tell you the story of the Marine on the beach!?” I said, “no!”

So, he continued:

Well, … there was this Marine, wandering around the beach, picking up pieces of paper one after another, examining each and then throwing it back to the ground, saying every time, “no, this is NOT it!”

Superiors became quite worried about the Marine’s behavior, so they said to themselves, “he must be losing his mind… he is due for an exam!” So, they took in the Marine and put him through many, many tests. At the end, they concluded that he had surely gone mad, so they gave him his discharge paper and let him go ….

The soldier, excitedly looked at the discharge paper and said to himself: “Yes … THIS IS IT!”

Recommended Citation

Tamdgidi, Mohammad H. 2012. “Editor’s Note: To Be of But Not in the University.” Pp. vii-xiv in Decolonizing the University: Practicing Pluriversity (Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge: Volume X, Issue 1, 2012.) Belmont, MA: Okcir Press (an imprint of Ahead Publishing House).

The various editions of Decolonizing the University: Practicing Pluriversity can be ordered from the Okcir Store and are also available for ordering from all major online bookstores worldwide (such as Amazon, Barnes&Noble, and others).

For OKCIR posts on the topic of coloniality click on the links below:

Endnotes

- 1In their work, Global Citizenship and the University: Advancing Social Life and Relations in an Interdependent World (Stanford University Press, 2011), for instance, Robert A. Rhodes and Katalin Szelényi make this point clear by stating: “After all, pluriversity knowledge can be applied in a variety of ways, be that for humanitarian or mercantile purposes” (p. 108).

In other words, there can be more accommodative versus more radical and pathbreaking approaches to practicing pluriversity. This is obvious, since pluriversity in and of itself basically highlights the pluralist character of knowledge production in an institution, even at the epistemic level, and does not necessarily indicate whether or not a particular, open versus closed, model is predominant in guiding the knowledge production process.