Book Section: CHAPTER II—Omar Khayyam’s Treatises on the Straight Balance and on How to Use a Water Balance to Measure the Weights of Gold and Silver in a Body Composed of Them: The Arabic Texts and New Persian and English Translations, Followed by Textual Analysis — by Mohammad H. Tamdgidi

$20.00

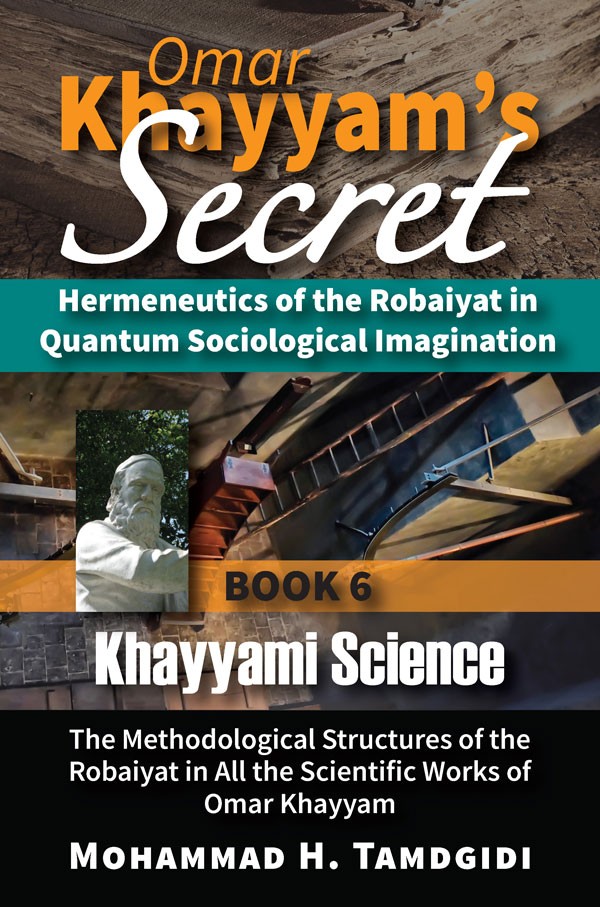

This essay titled “Omar Khayyam’s Treatises on the Straight Balance and on How to Use a Water Balance to Measure the Weights of Gold and Silver in a Body Composed of Them: The Arabic Texts and New Persian and English Translations, Followed by Textual Analysis” is the second chapter of the book Khayyami Science: The Methodological Structures of the Robaiyat in All the Scientific Works of Omar Khayyam, which is the sixth volume of the twelve-book series Omar Khayyam’s Secret: Hermeneutics of the Robaiyat in Quantum Sociological Imagination, authored by Mohammad H. Tamdgidi.

Description

Abstract

This essay titled “Omar Khayyam’s Treatises on the Straight Balance and on How to Use a Water Balance to Measure the Weights of Gold and Silver in a Body Composed of Them: The Arabic Texts and New Persian and English Translations, Followed by Textual Analysis” is the second chapter of the book Khayyami Science: The Methodological Structures of the Robaiyat in All the Scientific Works of Omar Khayyam, which is the sixth volume of the twelve-book series Omar Khayyam’s Secret: Hermeneutics of the Robaiyat in Quantum Sociological Imagination, authored by Mohammad H. Tamdgidi.

Sometime in his life, Khayyam wrote two essays, one on his proposed design of a Straight Balance (قسطاس المستقيم or Qesṫās al-Mostaqim, a type of steelyard balance) that accurately measured weights from a grain to a thousand coins of gold or silver, and another on how to use a water balance to measure the weights of gold and silver in a body composed of them without having to disassemble it. It is possible to consider that his proposed straight balance could be used also as a water balance to address the second problem noted above, but his treatises appear to be separate essays not related to one another, as commonly believed. Both writings were apparently aimed at avoiding fraud and deception in trade or payments, since they provided opportunities for the user to accurately weigh items of various light to heavy weights and to confirm how much gold and silver was contained in a body composed of them.

The two treatises have survived as two sections in a comprehensive book on balances and scales titled Mizan ol-Hekmat (Balance of Wisdom) completed in 515 LH (about AD 1121) by Abdorrahman Khazeni. In this chapter, following an account of how the two writings came to be found, Tamdgidi shares the Arabic manuscripts, along with his new Persian and English translations, of both of Khayyam’s treatises, one of which has been commonly titled رسالة فى الاحتيال لمعرفة مقدارى الذهب و الفضّه فى جسم مركّب منهما (Resālaẗ fi al-Éḥtiāl le-Maʾrefaẗ Meqdāri al-Z̧ahab wa al-Faẓẓah fi Jesm Morakkab Menhomā) (Treatise on [Avoiding] Fraud for Measuring the Amounts of Gold and Silver in a Body Composed of Them), and another usually titled قسطاس المستقيم (Qesṫās al-Mostaqim, or Straight Balance). An old Persian translation of the latter essay has survived, one which Tamdgidi also shares and translates into English. These are then followed by his analyses of the texts.

Although Tamdgidi’s purpose is to know what Khayyam had to say about his designed balance and how a water balance can be used to measure gold and silver in a body composed of them, his intention is not to be evaluative from a technical point of view. Rather, his purpose, as elsewhere in this book and series, is to understand the structures of Khayyam’s thinking as embodied in treatises devoted to solving applied scientific problems—in particular the distinction he makes between the geometric and algebraic methods of going about solving problems—and what the writings tell us about why and how he may have gone about composing a poetry collection, one that may have also been itself intended to solve a problem in human life in an applied way.

In Khayyam’s writing on balance we also find an interest in ratios and proportionality. We saw this already in the previous chapter of this volume, when we found him in his only extant writing on music to be interested in how ratios and proportionality “sound” differently. He even was interested in distinguishing between conjunct and disjunct types of ratios, and keeping track of how they differently sound. But that is just another way of his regarding ratios as not just pure abstract mental objects, but as real objects that in that case manifest as different vibrations and resulting sounds on a harp or stringed musical instrument. In his writings on balance, we see the same interest being pursued. Here, the air to water ratios of metals present a key solution to a practical problem of determining the weights of gold and silver in a body composed of them. Weighing things just in air won’t work, nor would it work weighing them in water only; it is the relation of the two that offers a real, not just abstract, solution to the problem.

Throughout both procedures, geometric and algebraic, Khayyam is dealing with ratios and proportionality, as if he has realized there is something special, something secret, in going about solving problems by focusing on not just how things appear as objects, but as how they relate to one another in a deeper sense. It is recognizing the relations among things that leads to solving problems, since things as such may give a misleading sense of what reality is at the surface when we observe it. It is the same sentiment that would lead the poet to say that he knows how things appear to exist or not, or what the deeper meaning of what high or low is, since such insights cannot be fully cultivated without a relational way of understanding them. It is for this reason that he wishes to investigate abstract objects visually and geometrically, and it is the same wish that can lead him to cultivate a poetic approach even to scientific investigation—and vice versa, to see his poetic work as simultaneously scientific work.

We should not be surprised to find Khayyam taking ratios and proportionality seriously in his work. After all, the science of astronomy, for which he was especially trained, relies fundamentally on a deep and practical understanding of ratios and proportionality. Using the astronomical instruments prevalent at the time, such as the astrolabe, offered opportunities to solve problems and make precise calculations in terms of the manipulation of ratios and considerations of proportionality. Vast distances measured above become accessible to the senses and manipulatable in calculations when translated into geometric and algebraic methods used in tandem for solving problems. What led Einstein to make his discoveries was also essentially a similar attention to matters of relationality—or what came to be known in his case as relativity—of things previously taken for granted in absolute terms. Khayyam, due to his belief that motion does not enter the study of geometry, of course did not delve into matters of motion and time the way Einstein did centuries later. But the essence of their visions of reality, in terms of seeing the relativity of things that are often taken for granted as absolute truths when studying reality, is the same.

Significantly, then, if Khayyam, as a systemic thinker, were to compose poetry, we would expect that the elements of the parts representing his poetic output would be subject to such relativistic consideration. A quatrain expressing a sentiment could then be misunderstood if taken out of the context of the broader collection narrative he intended to express in his poetic composition. A “balanced” reading of his poems, therefore, would require understanding each quatrain not in isolation from others, but in terms of the place it occupies in the broader scheme of his poetry as a whole, the same observation being in fact relevant even when we consider his poetry in the context of his worldview and philosophical outlook as a whole.

Recommended Citation

Tamdgidi, Mohammad H. 2023. “CHAPTER II—Omar Khayyam’s Treatises on the Straight Balance and on How to Use a Water Balance to Measure the Weights of Gold and Silver in a Body Composed of Them: The Arabic Texts and New Persian and English Translations, Followed by Textual Analysis.” Pp. 61-118 in Omar Khayyam’s Secret: Hermeneutics of the Robaiyat in Quantum Sociological Imagination: Book 6: Khayyami Science: The Methodological Structures of the Robaiyat in All the Scientific Works of Omar Khayyam. (Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge: Vol. XIX, 2023. Tayyebeh Series in East-West Research and Translation.) Belmont, MA: Okcir Press.

Where to Purchase Complete Book: The various editions of the volume of which this Book Section is a part can be ordered from the Okcir Store and all major online bookstores worldwide (such as Amazon, Barnes&Noble, Google Play, and others).

Read the Above Publication Online

To read the above publication online, you need to be logged in as an OKCIR Library member with a valid access. In that case just click on the large PDF icon below to access the publication. Make sure you refresh your browser page after logging in.