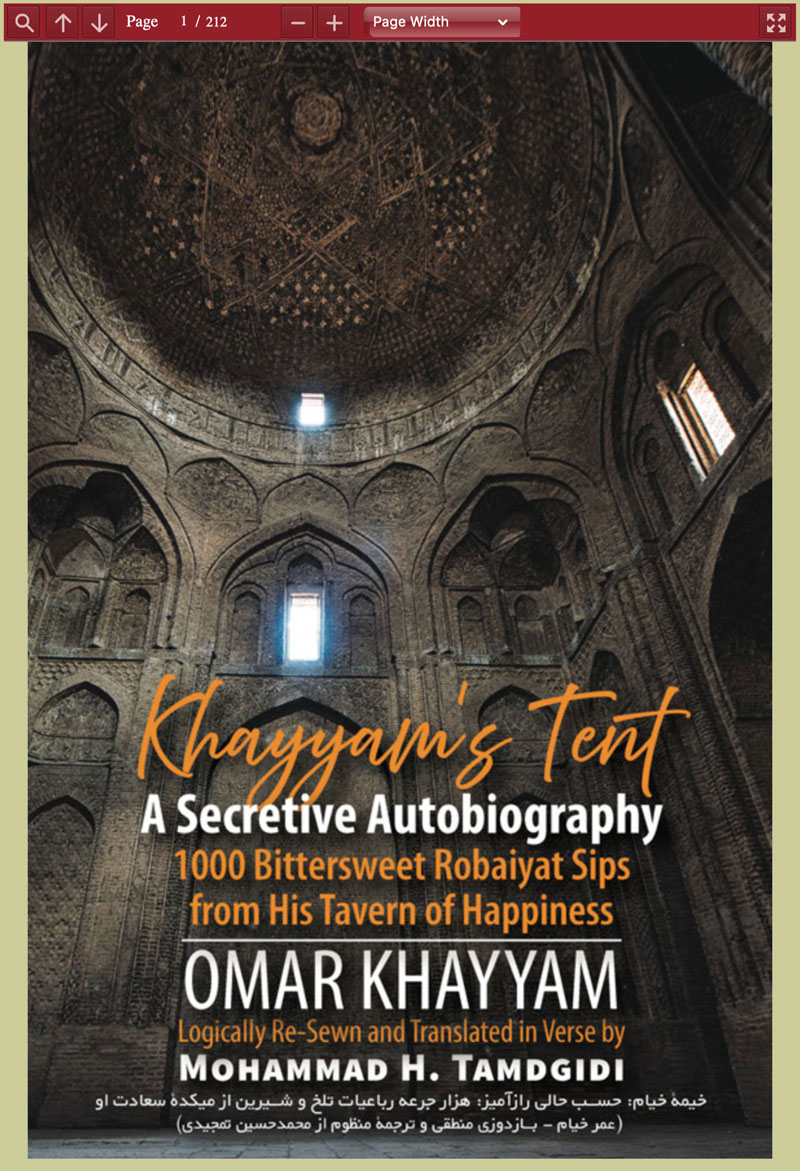

The following essay by Mohammad H. Tamdgidi is the Introduction (pp. 27-88) to the 12th and last book of his series Omar Khayyam’s Secret: Hermeneutics of the Robaiyat in Quantum Sociological Imagination (Okcir Press, 2021-2025). The Introduction’s Section 4 subtitled, “The Islamophobic and Islamophilic Colonialities of Edward FitzGerald’s “Rubáiyát”: Decolonizing How He World-Famously Distorted Omar Khayyam’s Robaiyat” is posted separately as linked, so is not included below.

The last book of the series is subtitled, Book 12: Khayyami Legacy: The Collected Works of Omar Khayyam (AD 1021-1123) Culminating in His Secretive 1000 Robaiyat Autobiography. The Introduction was subtitled “Introduction to Book 12: Toward A Textually and Historically More Reliable Biography of Omar Khayyam (AD 1021-1123) Based on the Findings of This Series.”

Toward A Textually and Historically More Reliable Biography of Omar Khayyam (AD 1021-1123) Based on the Findings of the 12-Book Omar Khayyam’s Secret Series

This book, the 12th and the last in the Omar Khayyam’s Secret series, is dedicated to presenting the collected works of Omar Khayyam and a condensation of the findings of the series in a single volume.

In the preface, recapping the findings of the previous books of the series, I summarized how a method framed in the quantum sociological imagination helped solve the riddles of Khayyam’s life and works in this series.

In this introduction I will first offer an overview of the organization of this volume comprising the collected works of Khayyam. Then, in a second section,

I will discuss the scientific requirements for the study of Khayyam’s biography. In a third section I will delineate the new findings of this series that make possible a textually and historically more reliable biography for Khayyam. And in a fourth section, before concluding this introduction,

I will also offer a critical commentary on the role played in modern times by Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát in distorting his legacy (this section is posted separately as linked).

1. The Collected Works of Omar Khayyam: The Organization of This Last Book of the Series

In this volume I will introduce and share the original texts of Khayyam’s works in Persian and Arabic (with Persian translations) and in my new English translations of them along with a summary of the series’ findings in analyzing the works.

Three other chapters will also be included. One on the discovery and reconfirmation of Omar Khayyam’s true dates of birth and death respectively, offering (beyond those previously reported and discussed in Books 2 and 3 of series) further comments on the errors made by Swāmi Govinda Tīrtha in this regard.

Another chapter will discuss Khayyam’s work in astronomy and its relation to astrology, and a third chapter will explore the role he played in the design of Isfahan’s North Dome.

In Chapter I, I will summarize how the discovery and reconfirmation respectively of the true dates of birth and death of Omar Khayyam (AD 1021-1123) were reported in Books 2 and 3 of this series; I will then explain more, and further demonstrate, the errors made by Swāmi Govinda Tīrtha in using Khayyam’s reported horoscope to determine Khayyam’s birth date.

My study resulted in the finding that there was one, and only one, date between the years AD 1018 and AD 1055 that definitively fulfilled all the requirements of Khayyam’s reported horoscope for any degree of Gemini. That Gemini degree was 18˚, on which the Sun-Mercury Samimi (Cazimi) fell on that same degree of the Ascendant. The date was, in the Gregorian calendar, June 10, AD 1021, at sunrise, Neyshabour’s time.

It was nearly a four-minute period from 4:43:56 a.m. to 4:47:55 a.m., exactly at sunrise. During this short interval of time, the Gemini was Ascendant, the Sun and the Mercury were Samimi (Cazimi) on the same degree of the Ascendant 18˚ of Gemini (being in the Samimi distance of 8, that is, less than 16, minutes from each other), and Jupiter was positioned on the 11th degree of Libra, within a Taslees/Trine-fulfilling distance of about 113 degrees from the Sun and Mercury Samimi (Cazimi), observing them both.

I also reconfirmed that the true date of Omar Khayyam’s passing was the date historically known and reported for him. Khayyam died in 517 LH, corresponding to AD 1123, and 502 SH. At the time of his passing, he was a 102 solar years old centenarian.

In Chapter II, I will introduce and share the Persian text of Omar Khayyam’s Treatise on the Science of the Universals of Existence (“Resaleh dar Elm-e Kolliyat-e Vojood”) based on which my new English translation will also be offered.

I devoted Book 4 of this series to a careful study of this important keepsake treatise by Khayyam, since it provides a synopsis of his worldview as written later in life; for this reason, it is befitting that his collected works in this series also begin with this treatise.

I concluded in Book 4 that the date of Khayyam’s writing the treatise must have been around 488 LH/AD 1095-96, about three years after the deaths of Nezam ol-Molk and Soltan Malekshah. At that time Khayyam (b. AD 1021) would have been about 74-75 solar years old.

This is an age at which a request for a keepsake treatise would be plausible. Khayyam would have of course not known at the time that he was going to live to the solar age of 102, especially given the life-threatening times that followed the deaths of Nezam ol-Molk and Soltan Malekshah.

In Chapter III, I will introduce and present Omar Khayyam’s annotated Persian translation of Avicenna’s “Splendid Sermon” originally delivered/written in Arabic. I shared the treatise in my new English translation and studied it in detail (in relation to the Arabic text of Avicenna’s original sermon and its English translation) in Book 5 of this series.

In the lunar year 472 LH (AD 1079-1080), Khayyam was invited in Isfahan by persons whom he called “brothers” to translate into Persian and explain a sermon written in Arabic by Avicenna (Ibn Sina). Given the request, and the fact that Khayyam has been reported—most notably by Zahireddin Abolhasan Beyhaqi, author of Tatemmat Sewan el-Hekmat (Supplement to the Chest of Wisdom)—as having been regarded as the Avicenna of his time, the request itself is historically and biographically significant.

In his own writing, written a year later, one that I will share in the following chapter—Khayyam in fact refers to Avicenna as a teacher with whom he had held conversations, presumably as a young student. Khayyam (b. AD 1021) delivered his annotated Persian translation of Avicenna’s Splendid Sermon when he was about 58-59 solar years old in 472 LH (AD 1079-1080).

In Chapter IV, I will introduce and share an important treatise written in Arabic by Omar Khayyam titled “Resalat fi al-Kown wa al-Taklif” (“Treatise on the Created World and Worship Duty”), one that has been titled variously, including as a treatise on “Being and Duty,” “Existence and Duty,” “Being and Obligation,” “Existence and Obligation,” and “Being and Necessity,” among others.

I offered my updated Persian and new English translation of this treatise and studied it in detail in Book 5 of this series. In my introduction I will explain why the most expressive title in English for the treatise based on its purpose as stated by Khayyam in the writing itself is “Treatise on the Created World and Worship Duty.”

The date of the writing of the treatise is known. It was written by Khayyam in the year 473 LH/AD 1080-1081 (as noted in its introduction itself), that is, about a year after Khayyam presented his annotated Persian translation of Avicenna’s Arabic “Splendid Sermon” in Isfahan, one that I share in Chapter III of this volume. The treatise was written when Khayyam (b. 412 LH/AD 1021) was about 59-60 solar years old.

In Chapter V, I will introduce and present Khayyam’s Arabic text and my updated Persian and new English translation of the manuscript that has been commonly entitled “Answers to Three Questions: On the Necessity of Contradiction, Determinism, and Survival.”

However, the only extant old manuscript (accessible online in the Chester Beatty’s Digital Collections) based on which the later editions of the manuscript have been reproduced offers only “On the Necessity of Contradiction” as a title for this writing. I studied this treatise in Book 5, explaining further its title and why it was a part of a three-part treatise addressed to Abu Taher to whom Khayyam also dedicated his treatise in algebra.

The texts of all the three parts of Khayyam’s treatise on existence were composed in the same year by Khayyam in 473 LH (AD 1080–1081), when Khayyam (b. 412 LH/AD 1021) was visiting Fars. He would have been about 59-60 solar years old at the time.

In Chapter VI, I will introduce and share the second part of Omar Khayyam’s Arabic treatise on existence, addressed to Abu Taher.

I offered my updated Persian and new English translations of this treatise and studied it in Book 5 of this series. Khayyam’s “Treatise on Existence” (“Resalat fi al-Vojood” or, in Persian, “Resaleh dar Vojood”), also known variously as “Treatise on the Study of Attributes” or “Treatise on the Attributes of the Attributed,” is one of the more well-known writings of Khayyam.

It was mentioned by Beyhaqi in his biographical entry on Khayyam in Tatemmat Sewan el-Hekmat (Supplement to the Chest of Wisdom) along with another treatise I have shared in Chapter IV of this volume, “Resalat fi al-Kown wa al-Taklif.”

In Chapter VII, I will introduce and present the third part of Omar Khayyam’s treatise on existence addressed to Abu Taher, which I also studied in Book 5 of this series, providing my updated Persian and new English translation for it.

The treatise is one that has been titled “The Light of Intellect on the Subject Matter of Universal Science”; however, the actual title of the treatise as found at the beginning and at the end of its only surviving manuscript is “Treatise on Existent” (“فى الموجود”).

In my introduction I will explain the story behind the longer title hitherto given to this important treatise by Khayyam, and how this third part of his treatise on existence fits with the other two presented in the previous two chapters of this volume.

This treatise and the first and second parts shared in the previous chapters need to be considered as independently written but interrelated parts of a broader treatise on existence Khayyam wrote—in the first part focusing on the topic of the necessity of contradiction, in the second on the study of attributes, and in the third on the topic of “existent” as the proper subject matter of universal science.

They were all written in 473 LH (AD 1080–1081) along with Khayyam’s “Resalat fi al-Kown wa al-Taklif,” a year following the writing of his annotated Persian translation of Avicenna’s “Splendid Sermon.” So, he would have been then about 59-60 solar years old.

In Chapter VIII, I will introduce and share an Arabic treatise commonly titled (also) as “Answer to Three Questions,” one that I studied in Book 5 of this series, providing my updated Persian and new English translation for it.

The addressee of Khayyam is not identified by name in one of the manuscripts, but only by his honorary title. However, in another extant manuscript of the treatise, the addressee is identified as “Jamaleddin ʿAbdol-Jabbar Ibn Muhammad al-Moshkavi.” The titles by which he is addressed by Khayyam, Seyyedana al-Sheikh ol-Rais Amin ol-Hazrat and also Seyyedana al-Sheikh Jamal ol-Zaman, speak of the high status, both intellectually as well as politically, of the person as a Shia thinker.

The details of their acquaintance become evident as we read the manuscript. This treatise by Khayyam is significant both substantively and biographically in terms of the clues it provides regarding Khayyam’s whereabouts at one or another time of his life. In my introduction I will share a few important biographical revelations gained from this text.

Based on certain biographical details given by Khayyam in the treatise, it can be safely concluded that it must have been written sometime before the year 492 LH (about AD 1098) when Abu Taher died, and certainly after the three-part treatise on existence written by Khayyam to Abu Taher about two lunar decades earlier.

In Chapter IX, I will introduce and present the brief Arabic treatise of Khayyam in music on the topic of tetrachords, titled al-Qowl ʾAlâ Ájnās al-Laz̧i bel-Árbaʾaẗ (A Commentary on the Tetrachord Genera). I studied this treatise in Book 6 of this series, providing my new Persian and English translation for it.

The date of writing of Khayyam’s brief treatise in music on tetrachords is not known. In his treatise on Euclid, which is definitively known to have been written at the end of Jumadi al-Avval of the year 470 LH (late December AD 1077)—because it is stated at the end of its manuscript as such—Khayyam refers to a treatise he had previously written on a problem in a book on music, a treatise titled Sharḥ al-Moshkel men Ketāb al-Moosiqi (Explanation of a Problem in the Book on Music).

So, some scholars, including the late Jalaleddin Homaei (1900-1980), have conjectured that this brief treatise is a part of that presumably longer treatise on music; and if that is the case, they say, then it must have been written earlier than 470 LH. However, as I will explain in my introduction to the treatise, I tend to believe that Khayyam’s brief treatise on music was a stand-alone treatise and not part of the other presumably longer treatise in music Khayyam wrote, one that is not yet extant.

In Chapter X, I will introduce and share the Arabic manuscripts, along with my new Persian and English translations, of two treatises by Khayyam, one commonly titled Resālaẗ fi al-Éḥtiāl le-Maʾrefaẗ Meqdāri al-Z̧ahab wa al-Faẓẓah fi Jesm Morakkab Menhomā (Treatise on [Avoiding] Fraud for Measuring the Amounts of Gold and Silver in a Body Composed of Them), and another usually titled Qesṫās al-Mostaqim, meaning Straight Balance.

An old Persian translation of the latter essay has survived, one that I also share and translate separately into English. Sometime in his life Khayyam wrote two essays, one on his proposed design of a Straight Balance (Qesṫās al-Mostaqim, a type of steelyard balance) that accurately measured weights from a grain to a thousand coins of gold or silver, and another on how to use a water balance to measure the weights of gold and silver in a body composed of them without having to disassemble it.

Fortunately the two essays have survived as two sections in a comprehensive book on balances and scales titled Mizan ol-Hekmat (Balance of Wisdom) completed in 515 LH (about AD 1121) by Abdorrahman Khazeni, a younger contemporary of Khayyam who was reportedly one of his pupils and had joined him in the team of astronomers tasked with reforming the solar calendar.

In Chapter XI, I will introduce and present the Arabic manuscript, a Persian translation by the late Gholamhossein Mosaheb (1910-1979), and my new English translation based on the latter, of a treatise by Omar Khayyam known as “Treatise on Dividing A Circle Quadrant.”

I studied this treatise in Book 6 of this series. It is not known when exactly Khayyam wrote this treatise since no date is given in the treatise itself. However, in the treatise Khayyam expressed his wish that at a later date when circumstances allow he planned to write a more comprehensive treatise in algebra, expanding on the brief classification of the equations of first to third degrees he introduces in the treatise on dividing the circle quadrant.

We know that Khayyam fulfilled that plan, by writing his well-known treatise on the proofs of problems in algebra and equations. So, at least we know definitively that the treatise on dividing a circle quadrant was written earlier than Khayyam’s major treatise in algebra, one that I will share in the next chapter of this volume. However, since we do not know when exactly Khayyam wrote his major treatise in algebra itself, the exact dates of writing of neither of the two treatises are known.

In my introductions to the chapter and to one that follows (sharing Khayyam’s treatise in algebra) I suggest that the year 466 LH (about AD 1074, when he was about 53 solar years old) may be a plausible date for Khayyam’s writing this treatise, three lunar years before 469 LH when I have also proposed to be the date of completion of Khayyam’s treatise in algebra.

In Chapter XII, I will introduce and share Omar Khayyam’s major treatise titled Treatise on the Proofs of Problems in Algebra and Equations. The Arabic text of the manuscript along with its Persian translation published in 1960 in Iran by the late Gholamhossein Mosaheb (1910-1979) will be presented, followed by my new English translation of the text based on Mosaheb’s Persian translation.

I studied this treatise of Khayyam from a hermeneutic perspective in Book 6 of this series. As far as Khayyam’s own valuation of the place of his treatise in algebra among his works is concerned, one can show based on his own comments included in the treatise itself that he regarded it to be as significant a contribution in mathematical sciences as he considered to be the contribution of his treatise on the universals of existence to spiritual philosophy (one I studied in Book 4 of this series, and is included in Chapter II of this volume).

Khayyam dedicated the treatise as a gift to his honored patron, Abu Taher, a chief judge in the Fars region about whom he speaks highly in the treatise’s introduction. Abu Taher, about whose full identity I will say more in my introduction to the chapter (as also shared in Book 6 of this series), was the same person to whom Khayyam addressed his three-part treatise on the philosophy and theology of existence, included in earlier chapters of this volume.

In Chapter XIII, I introduce and present Omar Khayyam’s major work titled “Treatise on the Explanation of Postulation Problems in Euclid’s Work.” The Arabic text of the manuscript along with its Persian translation published in 1967 in Iran by the late Jalaleddin Homaei (1900-1980) will be shared, followed by my new English translation of the text based on Homaei’s Persian translation.

I studied this treatise from a hermeneutic perspective in Book 6 of this series. We are fortunate to know, in his own handwriting (as stated in the original copy that the scribe of his treatise used to copy his own reaching us), exactly when Khayyam completed his treatise on Euclid’s Elements. The scribe of the extant copy of the treatise widely used today notes that he was copying from Khayyam’s own handwritten manuscript completed toward the end of Jumadi al-Avval of the year 470 LH (in December, in Gregorian calendar, of the year AD 1077). He had even noted the place of its original completion, in the “book house” or library of a city whose name is unfortunately missing or rendered illegibly. The scribe was copying his own copy of it in the year 615 LH, about a lunar century after Khayyam’s passing in 517 LH (AD 1123).

In Chapter XIV, I will offer my views on Khayyam’s other scientific works which are known to have existed but are not fully extant or are differently extant. I will comment on his works on reforming Iran’s solar calendar, and also discuss the issue of Khayyam’s views on astronomy in relation to astrology and why such a consideration is essential not only for understanding Khayyam’s scientific legacy, but also his other works, especially his Robaiyat.

In Chapter XV, I will share, as done and studied previously in Book 7 of this series, an updated all-variations-included edition of Omar Khayyam’s Nowrooznameh (The Book on Nowrooz) in Persian, and my English translation of the important literary treatise.

In my introduction, I will offer the background of the various extant manuscripts of Nowrooznameh and address the question of its attributability to Khayyam and the ongoing debates about this matter in Khayyami studies. The book Nowrooznameh is a coherent and well-organized book, in which its stated author, Omar Khayyam, continually reflects on the integrity of its subject matter and its purpose, reminding many times his promise and intention of keeping it focused and short to the extent possible.

It fulfills well its author’s stated goal at the beginning: “… discovering the truth about Nowrooz, which day it was for the Persian kings, why it existed, which king established it, how it was performed, why it is celebrated, and what the kings’ other ceremonies and their customs and manners were in any of their affairs.”

There is no reason to believe that the book was a joining of separately written chapters or sections written by different writers, not originally intended to comprise a single book. No scholar has ever succeeded in offering any proof that the treatise was written by anyone other than Khayyam and no text or information has ever been discovered to challenge the view that the book was authored by Khayyam, an authorship that is clearly acknowledged at the beginning of the manuscript and parallels the way Khayyam’s authorship of many of his other extant manuscripts have been noted in them.

Khayyam’s treatise on Nowrooz was completed following Soltan Malekshah’s death in 485 LH (AD 1092) and, as I argued in Book 7 of this series, it was most likely written around the same time his treatise on the universals of existence was written, that is 488 LH (AD 1095-1096), since it aims to influence Soltan Malekshah’s sons who were fighting for power following their father’s death.

In Chapter XVI, I share my study of the North Dome of Isfahan, one that I originally included in Book 7 of this series, to explain and demonstrate why its design must be regarded as a result of Khayyam’s architectural works related to his work in Isfahan as an astronomer tasked with reforming Iran’s solar calendar. I will first offer an historical overview of the events preceding, during, and following Soltan Malekshah’s 20-year reign from AD 1072 to 1092.

I will then revisit the key contributions Khayyam’s Nowrooznameh makes to understanding what the true function of the North Dome may have been. This will be followed by a critical exploration of the major studies done to date, both officially and also by various architectural historians, on the North Dome. I will then try to integrate the most reasonable aspects of the findings regarding the open and hidden functions of the North Dome before concluding the chapter.

I will argue that the North Dome was not only a dual-use structure intended for the annual celebration of Nowrooz and as a part of a wider structure intended to function as an astronomical observatory, but also a structure to whose design Khayyam contributed for both openly official and hidden personal reasons, amid whose designs we can find symbolic elements that speak to the spiritual heart of the Robaiyat.

Khayyam cleverly used a rare opportunity during his stay and work in Isfahan to design a building that embodied, beyond its official functions related to solar calendar reform and its needed observatory, his own philosophical and theological worldviews as well as the essence of his Robaiyat.

In Chapter XVII, I will share the texts and my new English translations of Omar Khayyam’s Persian and Arabic poems other than his attributed Robaiyat, also providing for the Arabic poems new Persian translations.

As I demonstrated in Book 7 of this series, significant philosophical, theological, and biographical pieces of information can be found buried in these poems, even to the extent of the presence of significant clues that point to his engagement in writing his Robaiyat, not as a marginal pastime, but as a major lifelong project of writing his autobiographical “book of life.”

Given their contents, I will also show that they can be classified into three categories: 1-Expressing doubt, 2-Expressing hope, and 3-Expressing joy. For two of these categories (first two) we can include the Persian poems as well as Arabic pieces. For the third category, we have Arabic poems.

The last and final Chapter XVIII of this volume is dedicated to presenting the Persian originals and my new English verse translations of Omar Khayyam’s Robaiyat comprised of 1000 quatrains, organized according to his own three-phased method of inquiry as described in his treatise “Resalat fi al-Kown wa al-Taklif” (“Treatise on the Created World and Worship Duty”).

I studied the question of attributability of the Robaiyat to Khayyam in detail in the concluding chapter of Book 7, and further offered my explanation of his poetic masterpiece in Books 8-11 of this series. The Robaiyat as re-sewn and presented in this series is a synoptic expression of all of Khayyam’s astronomical/astrological, philosophical, theological, scientific, and literary works shared in a poetically-rendered spiritual autobiography format.

The Robaiyat were not just a few poems written marginally by him; it was his magnum opus, a lifelong “secret book of life” that encapsulated the essential wisdom he wished to leave as a keepsake legacy, serving also as a way of offering him a Simorgh-like (Phoenix-like) lasting spiritual life. The triplicity of its logical form also mirrors the geometry of the “grand tent” Triplicity found in his true birth date chart, inspiring his pen name “Khayyam”—the tentmaker.

2. The Scientific Requirements for the Study of Omar Khayyam’s Biography

A textually and historically reliable biography of Omar Khayyam in the sociological imagination must be based on an understanding of how personal troubles and public issues relate to one another, both of Khayyam and those who study his life and works—an understanding that itself depends on the availability and reliability of resources and the application of sound scientific methods to investigating them.

Such a study must be first and foremost informed of the accounts shared in one form or another by Omar Khayyam himself, inclusive of all that have become extant.

For this reason, his primary works should be treated as the most reliable sources for writing such a biography. Of course, such sources must be evaluated for their attributability to him; however, once their attributability is affirmed based on reasonable documentation and textual analysis of them, we would have to regard those sources as the most important material based on which his biography can be reliably written, and against which the contribution of any information or opinions shared by others in various accounts must be substantively interpreted and judged.

Of course, even what Khayyam says about his life and times can be subject to variation, interpretation, or even judgment. The views he may have held about himself and his times could have changed over his lifetime, depending on the changing personal circumstances and the broader social conditions in which such views were expressed.

In a work such as his autobiographical Robaiyat, he may have even intentionally presented an evolutionary scheme of his changing views. However, even such changing views of himself and his times have primary investigative, interpretive, and evaluative values. We should keep in mind that like any of us, Khayyam lived conflicting social times and experienced intra- and/or interpersonal conflicts in relation to them.

So, just because we find contrasting or even seemingly contradictory views and attitudes in his works about his life and times, those views should not be regarded as having any lesser exploratory value. Rather, they must also be subjected to interpretation and explanation as part of his life-course.

Moreover, in the study of Khayyam’s primary texts, a transdisciplinary approach must be maintained throughout, since Khayyam himself was a transdisciplinary thinker and in his times the disciplines we have constructed today did not even exist as such.

The different fields he studied are overlapping folds of a unitary research, and the best way to conceptualize them is as concentric circles, superposed with one another as if they are folds of the same research. When he is writing in science, say, on algebra, we should not regard him as having abandoned his philosophical or theological considerations, nor his artistic and creative way of exploring his subject.

It will also be a poor investigative approach to consider for biographical investigation only those passages in which Khayyam talks about himself or his times.

That is because one may find valuable insights about him from his writings even based on why, what, and how he wrote (or not) about any subject or participated (or not) in any projects offered to him. For this reason, all his writings in any field must be treated as primary biographical material, whether the material is verbal, algebraic or numerical, expressed plainly or in metaphors, relating to geometrical, mechanical, musical, arithmetical, or even architectural or ornamental design topics.

A tale in a literary treatise can be a fold of his astronomical, astrological, or geometrical imaginations. A trope in a poem may shed light on a puzzle he solved or a measurement he made in astronomy, an algebraic equation solved poetically, a metaphor used for a line standing at once as a part of two geometrical objects.

It should not matter whether his text being studied is in prose or poetry, literary or philosophical, theological or scientific, involving astronomical calculations or astrological imaginations. A hermeneutic approach to the study of those works also requires that we pay attention to both what is present in them, and what is expected to be in them but is absent. Silences can matter as much as expressed opinions, while matters that are stated in veil should be studied as carefully as those explicitly stated.

Any investigative approach that disregards one or another form of primary text from Khayyam in an a priori way, without subjecting it to careful study, including for the purpose of evaluating their attributability to him, would be a poor application of scientific method.

Especially in the context of the life of a public intellectual such as Khayyam who according to many sources also engaged in secretive writing or veiled expression of his ideas, the texts must be subjected to hermeneutic analysis to decipher the meanings below surface textual or symbolic expressions, and this can be best done when his writings are studied not selectively but as parts of his works as a whole.

Nothing extant from him should be left out, and even if he himself refers to having written a text that is still not extant for us, that limited piece of information must also be regarded as worthy of careful consideration.

Whether written in Arabic or Persian, his works must be accurately translated for research purposes. Just “rendering” them will not be sufficient and may instead be severely misleading. If one just relies on English-translated material and is not familiar with Persian or Arabic to read the original texts, one would be significantly limiting one’s research, since improper translations or renditions can significantly distort the views expressed in the original language of the text being studied.

If we are fortunate to have multiple manuscript copies at hand of the same text, the existence of variations among them should be regarded not as a liability or reason to dismiss the variations but as an opportunity and invitation to devote special attention to the variations, and this must be done not selectively but inclusive of all the variations that have become extant.

Just because a Gemini degree in his horoscope has been found more readily in one manuscript to be A, and in another to be B, other manuscripts offering variations C or D, even if not popularly accessible, should not be ignored. Instead, they should be given equal attention, since there must have been a reason for the proliferation of such variations across the manuscripts over time. Existence of variations across manuscripts of the same text is not a limiting fact but is a green flag for further investigation of those particular passages.

Old manuscripts were copied by scribes living in different cultural and linguistic contexts and historical periods and having their own opinions of the texts they were copying. Inadvertent errors, or intentional changes (including the selections they made to copy some while excluding others), could have been introduced to the text depending on their points of view, the extent of corruption found in the manuscript being copied, or the degree of their understanding of the manuscript they were copying.

Moreover, it will be a serious mistake to dismiss variations of a given manuscript or specific passages in them because their copying are dated later in time than others available from an earlier date. As I have pointed this often beginning in Book 1 of the series, it is possible that a later dated manuscript was copied from an older text that is no longer extant.

So, it is not necessarily the case that a later dated manuscript is of any lesser value than an older dated source. A later dated manuscript may indeed be more reliable than an older dated text, being a result of scribal work that was done more carefully to preserve older material that had been found in verge of destruction or corruption.

However, we should also consider that this may not be always the case and ultimately the values of variations of a manuscript can be best judged based on substantive comparative analysis of the texts in the context of the study of Khayyam’s writings as a whole.

For the above reasons, scientific studies of Khayyam’s writings offering insights about his life must abandon a fetishism of “old manuscripts” being necessarily always more reliable or accurate than the later ones.

The transdisciplinary approach to the scientific study of Khayyam’s primary texts also requires doing away with arbitrary dismissal of one or another text from him, be they long treatises or single quatrains, simply because a passage or text does not fit our own (or our own time’s) preconceived notions of who he was and how he lived his life.

Studying each text in the context of all of Khayyam’s writings in a transdisciplinary way allows us to evaluate their meaning and attributability based on an understanding of all his texts rather than based on selective reading of them in the specific field in which they are written. The length of the passage is not necessarily an indication of the scope of its significance.

A brief statement of his birth horoscope, for example, may provide us with more valuable autobiographical material than an entire volume, or, as Khayyam himself put it, his brief treatise on the universals of existence can be judged to be worth volumes. Similarly, a single quatrain may speak more than a volume about a fact or event in Khayyam’s life.

Khayyam’s words, in prose or poetry, should always be treated as implying more than what they appear to say. Selective dismissal of a passage or attributable quatrain given in one manuscript at the expense of ignoring the variations of it found across many manuscripts can be detrimental to writing his biography, setting back generations of Khayyami studies.

Applying a transdisciplinary approach to all the extant copy variations of each manuscript assures that one-sided prejudgments are not made based on only one variation at the cost of disregarding others.

Furthermore, the application of a sound scientific method requires from us to be open to questioning our own long-held views about Khayyam’s life and works when new findings especially based on the study of his own primary works render such old views implausible and in need of revision. Those who habitually insist on holding on to old narratives about Khayyam’s life and works when presented with new evidence do not help the cause of advancing scientific Khayyami studies.

There is no way any progress can be made in Khayyami studies and in rethinking his biography in a more reliable way without openness to entertain reasonable doubts about even the most cherished myths or opinions held about his life. Unfortunately, we may find at times that those who have built careers writing about Khayyam based on old narratives are found to be even more reluctant to entertain new ideas about his life and works, rushing into making misjudgments about new findings.

That is not supposed to be how scientific ideas progress; otherwise, Khayyami studies will remain stagnant, repetitive, and serving cultish traditions built around him over time.

All that I stated above regarding the approach to manuscripts attributed to Khayyam himself should also be observed for biographical accounts written by others about his life and work, whether in premodern or modern times.

Some have tended to regard any account written about Khayyam by others, especially the old accounts, as being truthful or soundly judged by default. If today someone offers a point of view about anyone, we tend naturally to regard it as just an opinion of that person, inviting its critical evaluation based on a careful consideration of their sources.

However, when it comes to older accounts written about Khayyam, for some reason we have at times taken for granted that they must be truthful by default, and not just expressions of opinions. The historical accounts written about Khayyam are opinions of those offering them, and their accuracy and soundness in judgment should be subjected to critical study and substantive evaluation as well.

It can also happen that the accounts shared by others about Khayyam were themselves subject to revision, omission, or errors at the hands of the scribes copying the texts, and the more widely read and copied a text has been, the more such variations and errors may be found across its manuscripts.

For this reason, if there are variations among sources for the same account being given by the same person (such as, say, Nezami Arouzi), we are obliged not to disregard the variations simply because it is more convenient to consider only the one variation that has been traditionally more considered. Nezami Arouzi’s account of meeting Khayyam in Balkh, for example, is reported differently when we read it as shared by Yar Ahmad Rashidi Tabrizi in Tarabkhaneh (House of Joy), who claims to have read a manuscript written directly by Arouzi. When we say Arouzi said so and so about Khayyam in a meeting, we should always ask, according to which manuscript the account is given?

The issues having to do with errors and omissions by scribes in copying manuscripts also apply to the premodern accounts written about Khayyam’s life and works. The accounts given by Nezami Arouzi in his Chahar Maqaleh (Four Discourses) have been reported by experts in Iranian studies of old manuscripts to be notoriously inaccurate across its various chapters, as I discussed before in the series.

As a Persian saying goes, “one crow cry can become forty crow cries” in the retelling of a tale across generations. An old white-haired person (پير زال) reported to be visiting Khayyam’s grave, true or not, was somehow interpreted as being a female than a male, a mother than a sister, and so on, when no such specification were ever expressed or implied in the original telling of the tale. As another example, there has been absolutely no textual evidence found about Khayyam’s father being a tentmaker by trade, and the tale has been so often and widely repeated in the absence of other tales about his family that it has become taken for granted as a part of his biography.

The problem of manuscript variations also applies most prominently to those of the quatrains attributed to Khayyam. I discussed the problem of the attributability of the Robaiyat in detail in the last chapter of Book 7 and showed in Books 8-10 numerous examples of how one can navigate across variations for the quatrains.

In this regard also it was important to evaluate the attributability of the quatrains based on the variations found, and decide on their attributability (or even the most reliable variation among many) in the context of all, not just poetic, writings of Khayyam.

Here also, the trap of circular reasoning must be avoided in choosing one or another quatrain as being a “yardstick” to select others, without having studied all of Khayyam’s writings. If I say, “I was sad, but became hopeful and later happy,” and people only read the first part of my sentence, they would think I was sad all my life.

Selecting “yardstick” quatrains to judge attributability questions would be a poor application of scientific method, since it can lead to partial reading of a life’s tale. “Wandering” quatrains do not prove or disprove their attributability short of other findings, but they can provide wonderful insights about how particular quatrains and their contents and forms cross-fertilized (or aspects thereof, not) their associated poets’ works, or what scribes thought of them in their times when copying them.

A Robaiyat collection that was intended to be an autobiographical telling of Khayyam’s life would necessarily resist being an expression of a single point of view across the collection. It could have been the very purpose of Khayyam to share the evolution of his spiritual insights about existence in an autobiographical form, so taking each insight as if it represents the whole can lead to a misunderstanding of his worldview, and by implication, of his life and biography.

Moreover, just because composing isolated quatrains have been a traditional trend in Persian poetry writing, it does not necessarily follow that a non-traditional poet such as Khayyam would have not composed his “book of life” as a logically ordered collection of quatrains.

Since a Robaiyat manuscript directly written by Khayyam has not (yet) been found and all that we have are reporting of quatrains by scribes, I approached their selection based on the study in this series of all of Khayyam’s writings, rather than applying a circular logic in choosing some quatrains based on supposedly “yardstick” quatrains.

Applying the method framed in the quantum sociological imagination to the study of the Robaiyat allowed for the insight that his poems are not separate billiard balls juggled apart from one another or from his other treatises, but were regarded as existing in a spread-out way in all of his writing.

The quatrains were not separate grapes, but were found to be sips of the same unitary spiritual Wine of his poetry, as condensations of his worldview expressed in all his writings.

The quantum sociological imagination method called for a more challenging way of going about discovering his Robaiyat than by reading the quatrains themselves and arbitrarily authenticating some based on others while applying a circular logic.

All his writings had to be analyzed in relation to one another in a transdisciplinary way, the approach proving to be more fruitful, resulting in the discovery of his Robaiyat as a “book of life” (نامۀ عُمْر). From having read only reports of others about his life and works, we subsequently arrived at the point of hearing his life’s story in his own words as shared in the re-sewn tent of his 1000 Robaiyat autobiography.

3. Delineating the New Findings of This Series That Make Possible a Textually and Historically More Reliable Biography for Omar Khayyam

Below, I list and discuss the findings of this series that allow for researching Khayyam’s biography in a more textually and historically reliable way. I have elaborated on these findings in detail in various books of this series, some of which are also shared in summary in this volume’s chapters or their introductions.

Therefore, the following serve only as reminders of the issues I have discussed in more detail in the series, ones that need to be considered in future biographical research on Khayyam.

1) Omar Khayyam’s True Date of Birth (AD 1021) Discovered

Omar Khayyam’s exact birth date had not been reported in the past and no references to it appeared in old chronicles of his life, except for his astrological birth horoscope reported by Beyhaqi in his Tatemmat Sewan el-Hekmat (Supplement to the Chest of Wisdom), copy variations of which were also reported across manuscripts particularly regarding the Gemini degree given in the horoscope in abjad alphabet.

In 1941, in his The Nectar of Grace: Omar Khayyam’s Life and Works, the Indian scholar Swāmi Govinda Tīrtha proposed the idea of trying to determine his birth date by way of the study of his horoscope, since it provided specific information regarding the relative location of the Sun, Mercury, and Jupiter at the time of his birth.

That study led him to report the date May 18, AD 1048, for Khayyam’s birth date. However, in pursuing his project, Tīrtha made significant errors that I detailed in Book 2 of this series.

I will summarize and further reveal and explain in Chapter I of this volume (beyond those shared in Book 2) the errors made by Tīrtha when studying Khayyam’s horoscope.

Alternatively, I reported in Book 2 of this series my finding for the first time that Khayyam’s true birth date occurred at Neyshabour’s sunrise on Sunday, June 10 (in Gregorian calendar), AD 1021, corresponding to Safar 19th in the lunar year 412 LH, or Khordad 20 in today Iran’s solar calendar year 400 SH.

This also allowed us to learn not just the stated but also the unstated features of the full horoscope of his true birth date, including the locations of the other planets Saturn, Venus, Mars, and also the Moon.

The planets Pluto, Uranus, and Neptune had not been discovered in Khayyam’s time, so their locations in his true birth date chart are irrelevant for the hermeneutic study of Khayyam’s horoscope as reported by him—that is, for understanding how Khayyam himself would have interpreted his own birth chart based on the conventional and universally defined rules of interpretation in astrology in which he had been expertly trained, whether or not he agreed with them.

Despite Tīrtha’s important contribution of the idea of learning Khayyam’s birth date by way of his reported horoscope, his errors ushered decades of confusion in Khayyami studies ever since its publication in 1941, his mistaken date for Khayyam’s birth having caused a series of factual and interpretive puzzles in the study of Khayyam’s life and (by implication) date of passing, some of which I studied in detail in Books 2 and 3 of this series and will again outline below.

2) Omar Khayyam’s Historically Known True Date of Passing (AD 1123) Reconfirmed

Omar Khayyam’s date of passing had been reported in many old chronicles (and old Western sources) to be in the Islamic lunar year 517 LH (which translates in Western conversions to AD 1123), a date that has been etched on his modern tombstone in Neyshabour based on such historical chronicles.

However this historically established date was gradually abandoned in recent decades in favor of the date AD 1131, based on absurdly arbitrary reasons as I detailed in Book 2 of this series.

Even Tīrtha, who erroneously calculated the birth year of AD 1048 for Khayyam in his work published in 1941, was not persuaded to believe Nezami Arouzi’s tale, as shared only in one of the manuscript varieties of his work Chahar Maqaleh (Four Discourses).

Tīrtha asked, correctly in my view, how can someone claiming to be Khayyam’s pupil not know for such a long time that such a famous person so dear to him had died? That would be twenty lunar years before 526 LH since their last meeting on the reported date 506 LH, or fourteen lunar years before if we consider that Arouzi’s meeting with Khayyam took place in 512 LH according to another copy of the manuscript Tīrtha relied on, one reported to have been read in Arouzi’s own handwriting by Rashidi Tabrizi, the compiler of Tarabkhaneh (House of Joy).

Modern copies of Nezami Arouzi’s Chahar Maqaleh (Four Discourses) report his having met Khayyam in 506 LH in Balkh, noting that when he again visited Neyshabour in 530 LH, he learned that Khayyam had died “some” (the word used is ‘chand’ or چند) years before. Some have claimed the word is ‘chahar,’ meaning ‘four,’ leading them to conclude that Khayyam must have then died in 526 LH (AD 1131).

Then, for the day and month, they borrowed from a part of Tarabkhaneh (House of Joy) giving a unanimously regarded wrong or even seemingly illegible date for Khayyam’s birth, and arbitrarily assigned it to be Khayyam’s month and day of passing attached to AD 1131, one that has become prevalently used today.

In Book 2, agreeing with Tīrtha on his observation of the unbelievability of a claim made by a self-claimed student of Khayyam, Nezami Arouzi, about not having known then that the famous Khayyam had died 14 (or 20) lunar years before their last meeting on 512 LH (or 506 LH), depending on which manuscript of Chahar Maqaleh (Four Discourses) we rely on, I analyzed the other manuscript of the book as reported by Yar Ahmad Rashidi Tabrizi in Tarabkhaneh (House of Joy), finding it to be in fact a much more reliable account of Nezami Arouzi’s last meeting with Khayyam.

In the account, which I translated in Book 2 (pp. 203-204), Nezami Arouzi reports having met Khayyam in the year 512 LH, asking for his blessing for his own upcoming travel to Mecca for pilgrimage. Khayyam tells him in response that when Nezami returns from Hajj, he will find him buried in a location on which blossoms will be shed. Nezami Arouzi reports that three years after his pilgrimage he returned, finding that what Khayyam had predicted had come true, the rest of the story including parts that suggested Arouzi knew Khayyam composed quatrains.

The details of my study of the text are given in Book 2 in detail. By way of a superposed study of that text and those of others, I calculated that depending on the month in which pilgrimage to Mecca could have taken place during the three years, the date of Khayyam’s passing could be more reliably considered as having taken place in the year 517 LH. The alternative account would also explain why Nezami Arouzi would find Khayyam had died without him knowing it (given his having been away for pilgrimage, which could have taken a long time in those times).

The modern circulating manuscript copy of Chahar Maqaleh (Four Discourses) has been regarded both positively as a model of Persian prose and negatively (even ridiculed) by Iranian experts on old manuscripts regarding its notoriously wrong historical dates and accounts.

Since it had been a widely read and copied text, it must have undergone many revisions as far as its historical dates are concerned by scribes not informed of the factual aspects of the dates given in its accounts. I quoted some of the assessment and criticisms of it as shared by the noted Iranian scholar of old manuscripts, the late Mohammad Qazvini (see Book 2, pp. 184-185). In his view,

From the research and investigation undertaken in Chahar Maqaleh it becomes known that Nezami Arouzi, despite the height of status in virtuosity, and his forerunning superiority in literary matters, manifests weakness in the techniques of historiography, and historical errors such as mixing up of the names of famous personalities with one another, chronological antedating or postdating of dates, and imprecision in recording of events and ways of doing these have been committed numerously.

I think, to be fair to Nezami Arouzi, the possibility should be considered that the above weaknesses pertain to only the modern manuscript copies of Chahar Maqaleh (Four Discourses) which Qazvini examined. If Yar Ahmad Rashidi Tabrizi was reading of a manuscript written by Nezami Arouzi himself, then it is possible that the dates and events may have been given more accurately there.

In any case, my study of the true date of Khayyam’s passing in Book 2 resulted in the reconfirmation of the year 517 LH (AD 1123) for it, as it had been historically known and reported unanimously. Thomas Hyde (1636-1703) also reported the same date in his biographical entry for Khayyam published in Oxford in AD 1700.

Unfortunately, the prevalence of unscientific approaches in the study of Khayyam’s biography prevented the world from commemorating AD 1123 as his true date of passing, the result being that the 9th centennial of his death arrived in 2023 and passed despite the reminders expressed in this series launched in 2021 and its press releases sent globally.

The same can be said of this series’ timely reporting in 2021 of the arrival of Khayyam’s true birth date millennium in AD 1021.

Given Khayyam’s true date of birth (AD 1021), it can be concluded that his alleged date of death in AD 1131 would be implausible, given his solar year at the time of passing would then be 110 and even more than 113 in lunar years. Khayyam died a 102 solar years (or just turned 105 lunar years) old centenarian in AD 1123.

3) Omar Khayyam’s Horoscope: A Possible Biographical Source of His Personal Interest in Astronomy and Critical Attention to Astrology

As noted above, Khayyam’s date of birth was not directly known in the past in a straightforward way, but only indirectly by way of his birth horoscope. While there could be many reasons for such absence of a direct knowledge of his birth date, it is possible to consider that given that only he could have known its date, he chose to share it by way of his birth chart in order to draw attention to meanings implied in its features, meanings that can be interpreted universally by way of conventional definitions attributed to birth charts in the astrological imagination.

Did Khayyam intend to share certain ideas about his life by sharing his birth date via his horoscope? Is his horoscope, beyond giving an astronomical map of his birth date, an autobiographical note about himself?

He was an astronomer with intimate knowledge of astrology, agreeing with its rules or not. It is reasonable to consider that he may have meant to convey certain notions about his life by way of his horoscope.

For this reason, in Book 3 of this series, I studied in detail Khayyam’s horoscope begun in Book 2, this time asking how his horoscope, as stated, and when considered fully, including its silent and unstated features in reference to other planets and aspects not readily stated therein, could be astrologically interpreted.

The first implication of the existence of his horoscope, itself being a reliable text from him, is that Khayyam chose to express his birth date in the astrological imagination.

If he had allegedly not paid any attention to astrology—a point that can readily be refuted based on the study of his own treatises on the universals of existence as well as in his Nowrooznameh, even as inferred from the reported three tales of Nezami Arouzi in his Chahar Maqaleh where he portrays Khayyam as not believing in astrological rules yet as having been regarded as an authority in the field in his time—why did he share his birth date by way of his horoscope?

For biographical research, Khayyam’s horoscope can be studied in three ways.

One is treating the information given in the horoscope about the position of the Sun and the planets at the time of his birth as astronomical data so that using one or another ephemeris database one can discover the date and time when his birth took place.

Such an investigation is one that Tīrtha proposed. He erred in his calculations of it for the purpose, but by way of careful analysis his errors have been found in this series and corrected to arrive at the true date of birth for Khayyam.

A second way is the way of traditional astrological interpretation, that is, an investigation that assumes there are certain causal relations between the motion of the celestial bodies, on one hand, and human lives and events on Earth, on the other.

In his The Nectar of Grace (1941), Tīrtha also followed that line of inquiry, claiming that the horoscope for his (erroneously) discovered date for Khayyam’s birth—one in which even the position of Pluto, Uranus, and Neptune (planets that had not even been discovered at the time Khayyam lived) were listed and “interpreted” (with the assistance of his astrologer consultant)—“remarkably” coincided with what was known, or could be known, about Khayyam’s life.

I have not been interested in that line of inquiry at all in this series, since it does not lend itself to verifiable conclusions and information about Khayyam’s life and works, in the sense of Khayyam’s life having been somehow shaped by the motion of the spheres and their associated celestial bodies.

A third way of studying the horoscope is the hermeneutic approach, one that I pursued in Book 3 of this series, beyond the investigation begun in Book 2.

My argument has been that just because we do not believe in astrology today, it does not mean people in Khayyam’s time did not believe in it, which is a reason why establishing birth charts for newborns was practiced at the time. Besides, and this is most important to keep in mind, the horoscope of Khayyam is not that of just any person, but that of (and reported for himself by) Omar Khayyam who became the foremost astronomer of his time, with a deep knowledge of astrological rules, whether he believed fully in them or not.

Besides, he was also equipped with the scientific skills, astronomical tools, and deep philosophical and theological acumen.

Apparently, he chose to share his birth date not by giving it directly, but by way of his horoscope having features that can be universally interpreted according to conventional rules of astrology, implying certain information about the owner of the birth chart.

So, by understanding hermeneutically the interpretations usually given in astrology about the features of the horoscope as it was stated explicitly in the statement of the horoscope (or not, that is, remaining unstated, ones that can only be known if one knows the full horoscope and its map of other planet positions), we can gain an insight into how Khayyam himself would have regarded the meanings conveyed through the horoscope.

This does not mean necessarily that he agreed or not with the interpretations; it means that he was aware of what the conventional connotations associated with the features of his horoscope were in his time.

The interpretations he may have had of his horoscope, or even the very notion implied in horoscopes’ telling something about the relation of the motion of the spheres to human lives and events, can be found expressed in his Robaiyat.

The Robaiyat cannot even be fully understood without its explicit and critical engagement with the astrological imagination and its rules about the spheres shaping human life. However, remarkably, even the feature not stated in his horoscope but present in the wider map of his true birth date chart, can be found engaged with in his Robaiyat.

For instance, even though we do not find the presence of Triplicity (in Persian called “Grand Tent” or khargāh) explicitly stated in his reported horoscope as shared in Beyhaqi’s Tatemmat Sewan el-Hekmat (Supplement to the Chest of Wisdom), many meaningful references to Triplicity/khargāh relating to his life can be found in his attributed Robaiyat.

Likewise, the unstated presence of Venus being in the last house, in astrology implying pursuing works of art secretly, can be found in some of his attributed Robaiyat, and oddly, we find in the ceiling of the North Dome a pattern that has been unanimously regarded as the motion of Venus around the Sun as observed from the Earth.

The ceiling pattern includes five Cups in which the Venus motion pattern empties its radiations (see Chapter XVI of this volume).

I tried to understand in Books 2 and 3 of this series the inspirational significance the various stated or silent features of Khayyam’s reported horoscope could have had for Khayyam himself. By sharing that horoscope with us, Khayyam was saying, “I was born at the cusp of sunrise on a degree of Gemini when Mercury was on that same degree of Gemini at the heart of the Sun, and Jupiter was observing them both from a third of a circle’s Trine distance.”

All such statements are coded statements that can be deciphered and interpreted hermeneutically in the astrological imagination.

Besides, the features he chose not to state in the chart, as if kept hidden and secret are equally or even more important, since he assumed that only those versed in astronomy and the astrological imagination could reasonably learn and ask in turn where Saturn, Mars, Venus, and the Moon, also were positioned in his birth chart.

It was this third hermeneutic approach that I adopted in the study of Khayyam’s horoscope, one that led to new discoveries about Khayyam’s life and works.

The first and foremost implication of the presence of Khayyam’s horoscope as a condensed “book of life,” so to speak, among his extant works is the very fact that Khayyam paid attention to astrological matters, even to the extent of using it to convey information about his life and worldview.

We find him engaging with the astrological imagination even in his last and most important keepsake treatise on the universals of existence and in Nowrooznameh (The Book on Nowrooz), while his Robaiyat can be best understood as a critique of fatalistic astrological imagination.

In his quatrains, including their most cited and celebrated ones, Khayyam states that from the beginning of his life he was deeply preoccupied with the question of the role played by fate or chance in influencing human life.

He states that from the very beginning he was looking, spending tireless days and sleepless nights, for the pen and tablet of destiny and chance, discovering, having learned from his “teacher,” that such a “Jamsheed’s Cup” was his own soul.

If he grew up being told that his birth chart had one or another feature that pointed to one or another way of conducting his life, or a future life he was supposed to expect to come about, he would have naturally become deeply interested in astronomical sciences that in his time were also intimately interwoven with astrological imaginations.

Khayyam’s early teacher, Avicenna, was reportedly skeptical of astrology in his time, but his critique was more of the prevailing ways of going about understanding how heaven and Earth may be related. Khayyam may have grown up being deeply interested in finding more scientific ways of understanding the factors determining human life.

In this sense, Khayyam’s horoscope can be regarded as having posed the questions that originated his personal interest in astronomy, and the scientific, philosophical, theological, and astrological questions associated with it.

Being told since childhood what features his horoscope included, he may have wondered about how it told, or not, what will happen in the rest of his life, and the question of his life being predetermined (or not) must have preoccupied his mind continually.

Such a query could have confronted him at once as a deeply personal trouble as well as a fundamental public issue impacting human life in general. His life being predetermined, in other words, did not trouble him only personally, but he confronted it also as a public issue for humankind, worthy of being studied scientifically, philosophically, theologically, as well as artistically by way of poetry.

The theological implications of such an inquiry are also obvious. If our lives are predetermined and written in our birth charts, why would we find it reasonable to be judged in an “afterlife” for the good and bad of our behaviors, having been predestined for hell or paradise?

So, his personal interest in such broader “public issues” could have been ignited when considering his own reported personal horoscope.

4) The Biographical Significance of the Stated Feature of Samimi (Cazimi) in Omar Khayyam’s Horoscope: Possible Source of a Personal Trouble and Motivation and a Trope in His Robaiyat

Khayyam’s reported horoscope includes a stated feature called Ṣamimi (or Cazimi in its Latinized expression used today) in astrology. It refers to a celestial conjunction that requires a proximity of 16 or lesser minutes (not degrees) between Mercury and the Sun.

The feature implies that Mercury is “intimate” (hence the term “Ṣamimi” which means the same in Arabic or Persian) with the Sun, as if being “at the heart of the Sun,” absorbing the Sun’s enormous benefic energy that multiplies the intellective powers symbolically associated in astrology with the planet Mercury.

Those possessing such a feature in their birth chart, other aspects of their chart notwithstanding, are regarded in astrology as having superior intellective capabilities.

For instance, it is for this reason that Beyhaqi, following his sharing of Khayyam’s horoscope in Tatemmat Sewan el-Hekmat (Supplement to the Chest of Wisdom) at the very beginning of his biographical entry for Khayyam, continues to report that he had superior powers of memory—what we call today a photographic memory.

The point for us here is not to believe that somehow Khayyam’s traits were shaped by the stars, as considered in an astrological imagination. Rather, the implication of the presence of the feature in the horoscope is that Khayyam himself, in the cultural context of his work in astronomy and knowledge of astrology, may have been subject to doubt and ridicule for at least a period of his life by those who questioned the feature’s presence in his chart, accusing him of having instead in his chart a feature called by astrologers “combustion” (“burning”).

The latter refers to the situation where in a birth chart the planet Mercury is close but not close enough (i.e., outside the orb limits of the 16 minutes requirement) to the Sun, suggesting that the owner of the chart is “burned out” by the overwhelming power of the Sun. This implies that their intellective powers, instead of being amplified, are reduced.

The requirement of 16 minutes or less for a Samimi (Cazimi) condition indeed implies the use of precise astronomical observation for its measurement. If his horoscope had been read at the time of his birth and soon thereafter, reporting it to include the Samimi (Cazimi) feature, Khayyam may have also been told since childhood that his birth chart included a Samimi (Cazimi) feature.

However, given the circumstances of his early life being troubling for him (as reported on in his writings), he may have even himself doubted the accuracy of the Samimi (Cazimi) condition being met in his horoscope. Besides, more generally, the entire astrological notion of his (and human) life being shaped by the stars may have led him to become deeply interested in the science of astronomy which in his times was closely interwoven with astrological considerations.

Still, given that in his reported horoscope the condition is clearly stated as being that of Samimi (Cazimi), rather than that of “combustion,” Khayyam must have confidently concluded based on his own investigations that indeed his birth chart had such a feature. Having studied ephemeris data for Books 2, I was astonished to discover how accurately the sum of the features in Khayyam’s horoscope could have in fact been met for one and only one date and time, on Neyshabour’s sunrise on June 10 (Gregorian) of AD 1021.

In his attributed Robaiyat, Khayyam speaks of having been interested in the astrological claims of human lives being shaped by the “spheres.”

It is plausible to consider that his 18 years spent in Isfahan later as a solar calendar reformer equipped with advanced astronomical observatory tools of his time provided him with ample time and first-hand technical opportunities to learn for himself the motion patterns of Mercury in relation to the Sun, calculating them backward to his own birth date—therefore laying to rest any doubts even he may have had about having the Samimi feature in his birth chart.

We should keep in mind that the task of calendar reform and its associated calculations inherently involves predicting forward (and backward) in time the motions of the Sun in relation to the Earth and other planets. So, it is apparent that he could have done the same backward in time regarding the motions of Mercury in relation to the Sun based on the accurate observations made and data collected during his 18-year stay in Isfahan.

The above can also explain why we find Khayyam referring in several attributed quatrains to the notion of “burning” (or “combustion”) when expressing his complaints against the spheres, or when responding to his foes, cursing back at them that they were themselves to be “burned, burned-out, and burnable” in hell.

5) The Biographical Significance of the Silent Features of Triplicities and Venus Secrecy in Omar Khayyam’s Horoscope: Inspirations for His Pen Name and for the Trope “Sewing Tents of Wisdom”

I studied Khayyam’s birth chart carefully in Books 2 and 3 of this series, not from a traditional astrological interpretive point of view, but in order to understand hermeneutically how an accomplished astronomer and specialist in astrological knowledge such as Khayyam would have gone about interpreting the features present in his reported birth horoscope and possibly being poetically inspired by them.

One of the important results of the discovery of the true date of birth of Omar Khayyam (AD 1021) as reported in Book 2 of this series was that it established a textual basis for the inspirational origins of his pen name “Khayyam.” This was made possible given the finding of a dazzling array of Triplicities present in his true birth date chart.

Moreover, it was learning the correct Gemini degree (18) of his horoscope and the references made in several attributed Robaiyat to the Grand Tent (“Khargāh”) that provided a reliable textual basis for confirming the attributability of a collection of 1000 Robaiyat to him, since we found a non-wandering attributed quatrain in which the correct address of the Gemini being located in the “middle” (and not the beginning) part of Gemini, was mentioned, the quatrain also poetically expressing the notion of a candle wick woven of a thousand threads—one that I interpreted to be referring to a Robaiyat collection comprised of a thousand quatrains.

The Triplicities feature is not explicitly stated in Khayyam’s reported horoscope as found in Beyhaqi’s Tatemmat Sewan el-Hekmat (Supplement to the Chest of Wisdom). There is a reference to Trine aspectation of Jupiter observing the Sun-Mercury Samimi (Cazimi), but Trine aspectation does not necessarily imply the presence of a Triplicity feature in a birth chart.

Trine aspectation refers to the situation where a planet is about the distance of 120 degrees (more or less some “orb” degrees depending on the planets involved) from another planet (or the Sun). Triplicity, however, refers to a configuration where three celestial bodies are found to be in a roughly equilateral triangular relation with one another, and depending on which constellations they fall in, Triplicities can be of the Earth, Air, Fire, or Water elemental types.

Once the full chart of the true birth date of Khayyam is considered, it is found to be full of a dazzling number of nearly overlapping Air Triplicities.

I studied the astrological interpretive significance of this feature in Book 3 of the series, and showed in that volume, and later also in Books 8-11 of the series, several attributed quatrains that explicitly convey the notion of the existence of Triplicities in Khayyam’s birth chart and astrological imagination of his life.

Triplicity, because it has a triangular form, has been called in Persian astrological system “khargāh” (meaning “Grand Tent”), a trope that is used in several quatrains attributed to Khayyam in its astrological connotation of referring to Triplicity.

The existence of such attributed quatrains in my view offers another fold of confirmation for the attributability of those quatrains to Khayyam, since the notion of Triplicity is not explicitly stated in Khayyam’s reported horoscope and their existence would have only been known by a Khayyam familiar with the full features of his own horoscope.

There is also another silent (unstated) feature in Khayyam’s true birth horoscope that involves the planet Venus, associated symbolically with the arts, being located in the last (12th) house of the horoscope associated with secrecy (while being Sextile with the Moon, a benefic conjunction feature in astrology).

Such a feature would not have remained unnoticed by Khayyam who was versed in astrological imagination, and in fact, again, we find quatrains in which Khayyam refers to a feature of his life that calls for allowing secrecy to play a part in his life. The reference in a quatrain in his Robaiyat to the Moon and Venus being conjunct is also well-known, of course.

Khayyam could have been inspired by the existence of such features in his true birth date horoscope. Consequently, he could have used them as tropes in his poetry or as inspirations for conducting his life, whether he believed in astrology or not.

The above are discussed in much more detail in Book 3 of this series, but my purpose here is to show that the discovery of Khayyam’s true birth date and consideration of the full features of its horoscope allowed for new textually reliable ways of going about understanding the origins of his pen name, “Khayyam,” meaning “the tentmaker.”

His true birth date horoscope visually expresses several grand tents being sewn by a shared overlapping Sun-Mercury Cazimi feature vertex falling on the same degree of the Ascendant. Khayyam’s birth date and time, in other words, took place at a time many grand tents were being sewn by Mercury positioned at the heart of the Sun at sunrise. Being poetically inclined, therefore, Khayyam, the astronomer and with knowledge of astrological rules and symbols, could have been inspired to compose a quatrain about “the Khayyam who sewed tents of wisdom.”

No textual evidence has been found, in old sources extant for centuries or those found recently, suggesting that Khayyam’s name had anything to do with his father’s alleged occupation as a tentmaker. However, were that the case, the coincidence of such a familial name with the Grant Tent features of Khayyam’s horoscope could have seemed to Khayyam as being even more intriguing and inspiring.

Knowing about his chart since childhood, Khayyam could have been inspired to think of himself as someone who sewed tents of wisdom, leading him to adopt the takhallus (pen name) of Khayyam for himself as a poet engaged in composing his “book of life.”

A scientific approach to biographical research on Khayyam would open-mindedly welcome such alternative or additional explanations for his pen name, ones that are textually verifiable from his horoscope, conventional rules of astrological interpretation, and actual references made to the features in his attributed Robaiyat.

6) Omar Khayyam’s Three-Classmates Childhood Story Could Have Been True—Even Though Differently Told

A casualty of Tīrtha’s mistaken date for Khayyam’s birth has been the ready dismissal of the tale of Khayyam’s reported childhood friendships with the young future Nezam ol-Molk (famous vizier of Soltan Malekshah) and Hasan Sabbah (the founding leader of the Ismaeil sect who opposed the rule of Seljuks in Iran, resorting to assassination tactics that was also first used against Nezam ol-Molk).

The story suggests that as young classmates of similar age studying in Neyshabour, they vowed one day to support each other when they grew up, agreeing that whichever one first reached a higher position in the future, he would help the other two reach their goals as well.

So, according to the story, Nezam ol-Molk, having become a minister, was approached by the other two to fulfill their vow made when young. Khayyam, being interested in the sciences and administratively not ambitious, asked for and was given a grant allowance to pursue his interest, and Hasan Sabbah, being politically ambitious, was given office, one that he later betrayed by rebelling against the Seljuk empire and Nezam ol-Molk.

The alleged birth year AD 1048 as erroneously calculated by Tīrtha would make it impossible for such a tale to be even plausible, given that we know Nezam ol-Molk was born in AD 1018. Hasan Sabbah has been reported in some accounts as having died in AD 1124 a centenarian following Khayyam’s death in 517 LH (AD 1123).

An accompanying reasoning often used in rejecting the story of the three-classmates has been that a Khayyam born around the same time as Nezam ol-Molk (to render him a classmate of the latter) would have had to live an implausibly long time to die by AD 1123, let alone by the alleged and absurdly manufactured death date of AD 1131 for him as speculated today.

In such calculations one factor that has often been ignored is the difference between the length of lunar and solar years and ages. A hundred solar years old is about a hundred and three plus lunar years old.

Also, given that solar and lunar calendar months do not correspond exactly, someone born in a lunar year (without knowing the months) could be regarded as being born in one or another consecutive solar years, artificially or nominally adding to the age.

Besides, the impossibility of their being classmates has been judged using modern criteria of established grade-school years, as if they had separate school year gradations at that time by age, ignoring the possibility that the three young boys could have been in same class, but being of slightly different ages. Besides, the young (future) Nezam ol-Molk may have arrived late at his school given his father’s preoccupations as a treasurer amid rapidly changing political conditions of his time, finding Khayyam and Hasan Sabbah already there.

Hasan Sabbah was from the town of Rey originally (south of the present Tehran), and it was customary for young students seeking better known teachers who lived in cities like Neyshabour to be sent away to live with others to enroll in them. One may even consider Nezam ol-Molk’s idea of establishing branches of his Nezamieh schools across various cities and towns as a way of allowing more access for students to participate in such schools locally.