The following essay by Mohammad H. Tamdgidi is the Preface (pp. 11-26) to the 12th and last book of his series Omar Khayyam’s Secret: Hermeneutics of the Robaiyat in Quantum Sociological Imagination (Okcir Press, 2021-2025). The last book of the series was subtitled, Book 12: Khayyami Legacy: The Collected Works of Omar Khayyam (AD 1021-1123) Culminating in His Secretive 1000 Robaiyat Autobiography.

The preface was subtitled “How a Method Framed in the Quantum Sociological Imagination Helped Solve the Riddles of Omar Khayyam’s Life and His Robaiyat amid All His Works: A Recap from the Prior Books of This Series.” It served to provide a concise general summary of the basic findings of each of the 12 books of the series. Following the preface shared below, the two forewords contributed by Dr. Winston E. Langley and Dr. Jafar Aghayani Chavoshi to the last book of the series are also shared.

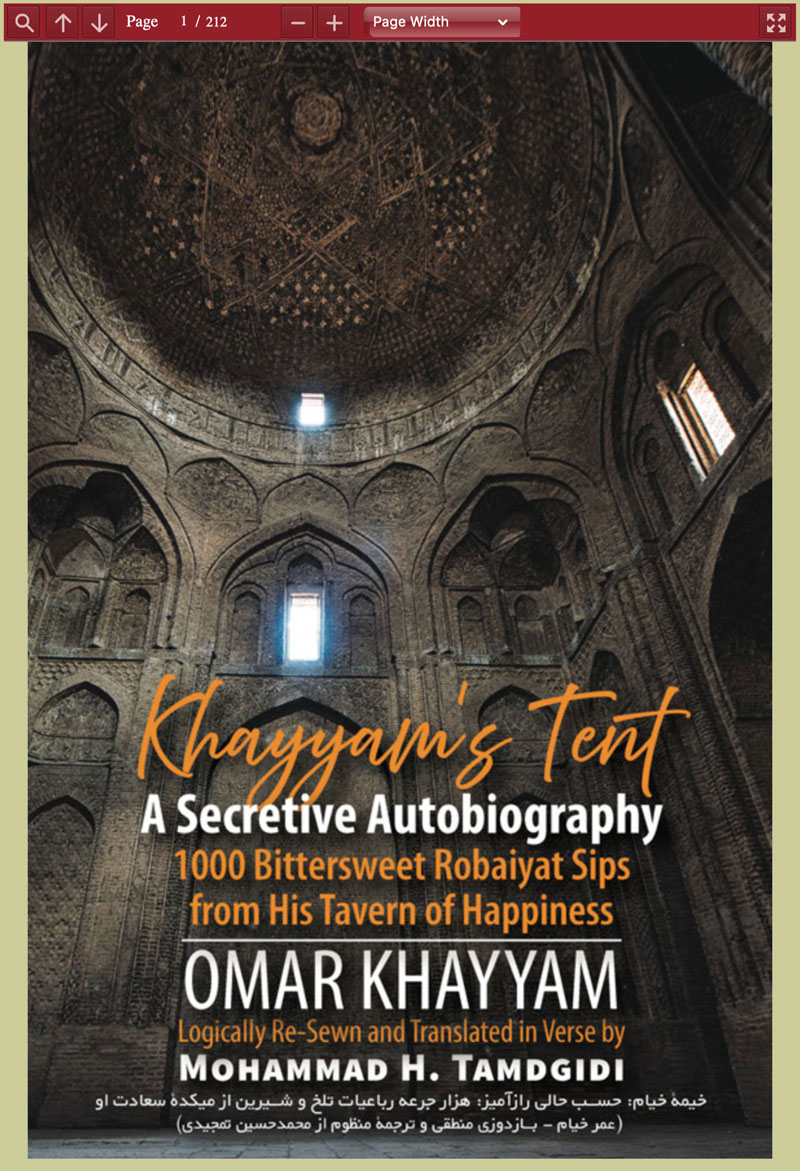

The series culminated in the separate publication of Khayyam’s Tent: A Secretive Autobiography: 1000 Bittersweet Robaiyat Sips from His Tavern of Happiness — by OMAR KHAYYAM (Logically Re-Sewn and Translated in Verse by Mohammad H. Tamdgidi) on June 10, 2025, the 1004th anniversary of Omar Khayyam’s true birth date, and 902nd anniversary of his true date of passing.

How a Method Framed in Quantum Sociological Imagination Helped Solve the Riddles of Omar Khayyam’s Life and His Robaiyat amid All His Works: A Detailed Summary of the Findings of the 12-Book Omar Khayyam’s Secret Series

Omar Khayyam’s Secret: Hermeneutics of the Robaiyat in Quantum Sociological Imagination is a 12-book series on the life and works of Omar Khayyam. Each book is independently readable, although it will be best understood as a part of the series as a whole.

In the series, I share the results of my long-standing research on Omar Khayyam, the enigmatic 11th/12th centuries Persian Muslim sage, philosopher, astronomer, mathematician, physician, writer, and poet from Neyshabour, Iran, whose life and works have remained behind a veil of deep mystery.

The purpose of my research has been to find definitive answers to the many puzzles surrounding Khayyam, especially regarding the existence, nature, and purpose of the Robaiyat in his life and works. To explore the questions posed in the series, I advance a new hermeneutic method of textual analysis, informed by what I call the quantum sociological imagination, to gather and study all the attributed philosophical, religious, scientific, and literary writings of Khayyam.

1. Summary of Book 1: New Khayyami Studies

The first book of the series was titled Book 1: New Khayyami Studies: Quantumizing the Newtonian Structures of C. Wright Mills’s Sociological Imagination for a New Hermeneutic Method.

The first book of the series was titled Book 1: New Khayyami Studies: Quantumizing the Newtonian Structures of C. Wright Mills’s Sociological Imagination for a New Hermeneutic Method.

In Book 1, following a common preface and introduction to the series, I developed the quantum sociological imagination method framing my hermeneutic study in the series as a whole. In the prefatory note I explained the origins of this series and how the study is itself a moment in the trajectory of a broader research project. In the introduction, I described how centuries of Khayyami studies, especially during the last two, have reached an impasse in shedding light on his enigmatic life and works, especially his attributed Robaiyat.

The four chapters of Book 1 were then dedicated to developing the quantum sociological imagination as a new hermeneutic method framing the Khayyami studies in the series. The method builds, in an applied way, on the results of my recent work in the sociology of scientific knowledge, Liberating Sociology: From Newtonian Toward Quantum Imagination: Volume 1: Unriddling the Quantum Enigma (2020), where I explored extensively, in greater depth, and in the context of understanding the so-called “quantum enigma,” the Newtonian and quantum ways of imagining reality. In the first book of the series, I shared a summary of the findings of that research amid new applied insights developed in relation to Khayyami studies.

In the first chapter, I raised a set of eight questions about the structure of C. Wright Mills’s sociological imagination as a potential framework for Khayyami studies. In the second chapter, I showed how those questions are symptomatic of Newtonian structures that still continue to frame Mills’s sociological imagination. In the third chapter, I explored how the sociological imagination can be reinvented to be more in tune with the findings of quantum science, and in the last chapter the implications of the quantum sociological imagination for devising a hermeneutic method for new Khayyami studies were outlined.

The most important and pivotal implication of the application of the quantum sociological imagination for the study of Khayyam’s Robaiyat is this. The basic insight of the quantum vision of reality is that each particle (and this is not limited just to light phenomena) is at once congealed and spread-out.

In my unriddling the quantum enigma (2020) I showed that there is no duality separating microscopic from macroscopic worlds from one another as far as the applicability of such a quantum vision is concerned, since such a duality is itself a result of leftover Newtonian distortions in our own lenses as observers. Consequently, applying such a quantum vision to the sociological imagination and to Khayyami studies is also possible.

I argued that Khayyam’s quatrains must have also existed at once locally in the quatrains themselves and also spread-out in all of his writings. Therefore, even if the attributability of specific quatrains to him is doubted, his Robaiyat can be rediscovered and the riddle of specific quatrains’ attributability to him solved by way of studying the Robaiyat as spread out in all of his extant writings.

The Newtonian way of imagining reality has been metaphorically compared to what I have argued (2020) to be itself an ideologically distorted “billiard balls game” way of imagining reality—ideologically distorted, since in fact even the billiard balls game can be imagined in a quantum way if our Newtonian lenses are rectified.

The Newtonian way of imagining reality may be broadly characterized as having eight notional attributes—namely, its Newtonian notions of (1) dualism, (2) atomism, (3) separability, (4) (subjectless) objectivity, (5) determinism (including its associated notion of predictability), (6) continuity, (7) disciplinarity, and (8) scientism.

To elaborate, the notional attributes of the Newtonian imagination are the following:

- Dualism: It assumes that an object must be either A and non-A and cannot be both at the same time;

- Atomism: Its micro unit of analysis of the object allows for separability of objects in an atomistic way;

- Separability: Its macro unit of analysis allows for separability of objects as if they came into being on their own and apart from one another;

- (Subjectless) Objectivity: It assumes that the object being observed can be understood apart from the role the observer plays in understanding and constituting it;

- Determinism: It assumes that there are predeterministic causes and consequences governing objects that render their development always predictable;

- Continuity: It assumes that objects are constituted by the influence of continuous chains of local-causations;

- Disciplinarity: It assumes that reality can be understood by way of fragmented disciplinary lenses whose knowledge can be truly understood apart from the knowledge of reality as a whole; and

- Scientism: It presumes the superiority of Western, Newtonian scientific way of thinking about reality, treating other cultural approaches to science as outdated and defective.

In Book 1, I suggested that the same eight-fold model to describe the attributes of the Newtonian way of thinking can be reframed to arrive at the quantum way of imagining reality characterized as having eight sets of attributes—namely its quantum notions of (1) simultaneity, (2) superpositionality, (3) inseparability, (4) relativity, (5) probability, (6) transcontinuity (or discontinuity), (7) transdisciplinarity, and (8) transculturalism.

- Simultaneity (not “duality,” nor “complementarity”): That reality is constituted of folds that can be best imaginable as superposed concentric part/whole circles where A can be at once non-A;

- Superpositionality: That such a superposed reality constitutes the micro world, rendering it as not being atomistic but being comprised of superposed folds;

- Inseparability: That such a superposed reality also constitutes the macro world as well, each part of which is constituted as an organic part of the whole reality;

- Relativity (or, subject-included objectivity): That objectivity can only be achieved if the subject observing the object is always treated as being a part of the object, treating the knowledge and reality of the object as not being independent of, but also constituted by, the observer;

- Probability: Given the superposed nature of reality, microscopically as well as macroscopically, its transformation can be at once determined and probabilistic;

- Transcontinuity (which is a term I prefer to call what is commonly referred to in quantum science as “discontinuity”): That reality by its superposed nature allows for transcontinuous, creative leaps to take place that can defy prior established local causal chains;

- Transdisciplinarity: That reality can be best understood in a transdisciplinary (not just disciplinary, nor interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary, since the latter two still presume the disciplines) way, by regarding the knowledge of each of its folds as a part of the reality as a whole;

- Transculturalism: Embracing all culturally variant ways of going about understanding reality that defy the presumed superiority of one cultural tradition over another.

Following the above considerations, in Book 1, I proposed that quantumizing the Newtonian in favor of a quantum sociological imagination invites the following considerations regarding each of which I offered illustrations, and from each of which I drew inspiration for Khayyami studies:

- From dualism to simultaneity (not “duality,” nor “complementarity”): Personal troubles and public issues can be at once one another and dialectically constituting of one another;

- From atomism to superpositionality: One can be constituted of a multitude of selves, some having personal troubles, others not, and some being at once troubled and troubling;

- From separability to inseparability: Public issues are not constituted just locally, communally, or nationally, but also world-historically;

- From subjectless objectivity to relativity (subject-included objectivity): Those who study the relation of personal troubles and public issues can also be themselves personally troubled and shaped by public issues of their times affecting their sociological imaginations, and even be themselves the source of personal troubles and public issues of their subjects;

- Reimagining causal patterns creatively from determinism to probability: Personal troubles and public issues are not predeterminable and predictable always, but are subject to probabilities and chances, and the same insight applies to resolutions one can bring to such troubles and issues;

- Reimagining causal chains also as causal leaps, from continuity to “transcontinuity” (also known as “discontinuity”): Lack of creativity can play a role in causing personal troubles and public issues, and their resolution can significantly depend on the application of creative cognitive and transformative methods;

- Reimagining sociology from disciplinarity toward transdisciplinarity: The sociological imagination can be most successful in understanding the interplay of personal trouble and public issues when it is conducted in a transdisciplinary way; and

- Reimagining science from eurocentrism to tansculturalism: The sociological imagination can be most successful in understanding the interplay of personal trouble and public issues when it is conducted in a transcultural way.

In Book 1, I illustrated in a figure how, by reimagining the elements of the sociological imagination in terms of overlapping and superposing circles, we can arrive at a non-dualistic, both/and, conception of elements that previously could only be imagined in terms of a formal, either/or logic characterizing the Newtonian way of imagining reality.

The implications of the quantum sociological imagination for Khayyami studies can therefore be highly significant. We can find that Khayyam was personally troubled in life about the existential troubles of humanity as a whole, his own personal troubles offering deep insights into how he went about understanding human existence, the reverse being equally true—suggesting that even a brief piece of his writings can shed light on his entire life and works.

We can find that atoms of his quatrains are not separate micro units of his poetry but integrally superposed parts of a larger narrative of his effort in understanding human life.

We can find that the broader public issues influencing, and being influenced by, his personal troubles were, in his view, not just local, communal, or even world-historical, but, given his spiritual worldview, encompassing astronomical/astrological, theological, and philosophical dimensions, requiring the study of all his treatises, not in isolation from one another, but as superposed folds of his unitary research work.

We can find that his study of human personal troubles and public issues is not just contemplative and one-sidedly objective, but deeply self-reflective, self-critical, as well as conceptually constitutive and transformative of their realities—rendering his Robaiyat as not being contemplative of, but also healing and transformative for, the personal troubles and public issues facing humankind. We can find that he was aware not only of matters of deterministic fate, but also of probabilistic chance, not dualizing them artificially but containing quantum visions where one can be at once the other.

We can find that he regarded predeterministic worldviews, scientific or religious, as being inadequate when dualized and separated from one another, being deficient on their own in understanding human troubles and issues, aiming instead for creative, poetic, pathways for appreciating and transcending their approaches.

We can find that his method was deeply and widely transdisciplinary and transcultural, not boxing his worldview in one or another rigid dogma, instead preferring a freethinking way of going about understanding human existence. We can find that such a method is itself required for understanding Khayyam’s life and works in a transdisciplinary and transcultural way, beyond artificial ways of separating his science from his philosophy, theology, astronomy, astrology, art, and poetic work, ways that treat the fields as being separable billiard balls to be juggled against one another.

We can instead treat them as being superposed, overlapping, folds of a unitary approach to understanding and transforming human life in favor of just outcomes. In short, we can find that to understand his views, and his Robaiyat, we need to read and understand all his treatises, and not just his quatrains, rather than treating them in isolation from one another, as if they are inherently separable.

Moreover, I argued that using the notion of “Khayyami” as a reference both to the person and to the tradition associated with him can offer a sociologically imaginative quantum device involving a language of simultaneity when referring to Khayyam’s life, works, and legacy—especially when it comes to the study of the attributed Robaiyat. Therefore, the notion can have significant methodological, substantive, and practical value for framing and conducting our Khayyami studies.

Overall, applying such a quantum method to the study of the Khayyami Robaiyat requires that we do not study the quatrains in isolation from one another and from the rest of the extant works of Khayyam, but undertake a careful study of all his works, as if his Robaiyat had a spread-out presence in them throughout. This explains why for the study of his Robaiyat I had to conduct this 12-book series research.

2. Summary of Book 2: Khayyami Millennium

The second book of the series was subtitled Book 2: Khayyami Millennium: Reporting the Discovery and the Reconfirmation of the True Dates of Birth and Passing of Omar Khayyam (AD 1021-1123). In the book, I laid down an essential foundation for the series by revisiting the unresolved questions surrounding the dates of birth and passing of Omar Khayyam.

The second book of the series was subtitled Book 2: Khayyami Millennium: Reporting the Discovery and the Reconfirmation of the True Dates of Birth and Passing of Omar Khayyam (AD 1021-1123). In the book, I laid down an essential foundation for the series by revisiting the unresolved questions surrounding the dates of birth and passing of Omar Khayyam.

Critically reexamining the manner in which Omar Khayyam’s birth horoscope as reported in Zahireddin Abolhassan Beyhaqi’s Tatemmat Sewan al-Hekmat (Supplement to the Chest of Wisdom) was used by Swāmi Govinda Tīrtha in his book The Nectar of Grace: Omar Khayyam’s Life and Works (1941) to determine Khayyam’s birth date, I uncovered a number of serious internal inconsistencies and factual inaccuracies that prevented Tīrtha (and, since then, other scholars more or less taking his results for granted) from arriving at a reliable date for Khayyam’s birth, hurling Khayyami studies into decades of confusion regarding Khayyam’s life and works.

I then shared in the book the detailed account of my own discovery of Khayyam’s true date of birth for the first time on 412 LH, or June 10, AD 1021, in the Gregorian calendar.

I then turned my attention to the task of definitively establishing the true date of passing of Omar Khayyam. Conducting an in-depth, superposed analysis of Beyhaqi’s Tatemmat Sewan el-Hekmat (Supplement to the Chest of Wisdom), Abdorrahman Khazeni’s Mizan ol-Hekmat (Balance of Wisdom), Nezami Arouzi’s Chahar Maqaleh (Four Discourses), and Yar Ahmad Rashidi Tabrizi’s Tarabkhaneh (House of Joy), amid other relevant texts, I reconfirmed and further discovered, in a textually reliable way, the date and time in which the poet mathematician, astronomer, and calendar reformer died as a solar centenarian, completing his 102nd solar year age—517 LH, or AD 1123, in the Gregorian calendar.

Notably, these discoveries were made and reported in 2021 just in time as we approached the first solar millennium of Omar Khayyam’s birth date on June 10, AD 1021 (Gregorian), at sunrise of Neyshabour, Iran, and the ninth solar centennial of his passing in AD 1123, likely also on June 10 (Gregorian), on the eve also of his birthday, closing the circle of his life’s “coming and going.”

3. Summary of Book 3: Khayyami Astronomy

The third book of the series, published together with the two preceding books of the series, was subtitled, Book 3: Khayyami Astronomy: How Omar Khayyam’s Newly Discovered True Birth Date Horoscope Reveals the Origins of His Pen Name and Independently Confirms His Authorship of the Robaiyat.

The third book of the series, published together with the two preceding books of the series, was subtitled, Book 3: Khayyami Astronomy: How Omar Khayyam’s Newly Discovered True Birth Date Horoscope Reveals the Origins of His Pen Name and Independently Confirms His Authorship of the Robaiyat.

Omar Khayyam’s true birth date horoscope, as newly discovered in this series, is comprised of a dazzling number of Air Triplicities (called in Persian astrology Khargāh or “Grand Tent”) sharing a vertex on a Sun-Mercury Samimi (Cazimi) point on the same Ascendant degree 18 of Gemini.

Among other features, his Venus, Sextile with Moon, also plays a lifelong, secretively creative role to intentionally balance his chart. These features would not have escaped the attention of Omar Khayyam, a master astronomer and expert in astrological matters, no matter how much he embraced, doubted, or rejected astrological interpretations.

In the third book, conducting an in-depth hermeneutic analysis of Khayyam’s horoscope, I reported having discovered the inspirational origins of Khayyam’s pen name (meaning “tentmaker”) in his horoscope. The long-held myth that “Khayyam” was a parental family name, even if true, in no way takes away from the new finding; it only adds to its intrigue.

My hermeneutic analysis of Khayyam’s horoscope in intersection with extant Khayyami Robaiyat also led me to discover an entirely neglected signature quatrain that I proved could not be from anyone but Khayyam, one that provides a reliably independent confirmation of his authorship of the Robaiyat.

I also showed how another neglected quatrain reporting its poet to have aged to a hundred is from Khayyam. This meant that all the extant Khayyami quatrains were now in need of hermeneutic reevaluation.

My further study of a sample of fifty Khayyami Robaiyat led me to conclude that their poet definitively intended the poems to remain in veil, that they were a collection of interrelated quatrains and not separate quatrains written marginally in pastime, that they were meant to offer a life’s intellectual journey as in a “book of life,” that the poems’ critically nuanced engagement with astrology was not incidental but essential throughout the collection, and that, judging from the signature quatrain discovered, 1000 quatrains were intended to comprise the collection.

It appears that, after all, “The Khayyam who stitched his tents of wisdom” was a trope that had its inspirational origins in Omar Khayyam’s horoscope heavens.

4. Summary of Book 4: Khayyami Philosophy

The fourth book of the series was subtitled Book 4: Khayyami Philosophy: The Ontological Structures of the Robaiyat in Omar Khayyam’s Last Written Keepsake Treatise on the Science of the Universals of Existence.

Having confirmed in the prior three books of the series the true dates of birth and passing of Omar Khayyam, his pen name origins, and his authorship of a robaiyat collection, in Book 4 I explored the origins, nature, and purpose of such a collection by applying the series’ quantum sociological imagination method to hermeneutically explore the ontological structures of the Robaiyat in Khayyam’s last written treatise on the universals of existence.

Khayyam’s treatise, found in the early 20th century and still largely ignored or misread, radically challenges the mythical narratives built over the centuries about him as one who thought existence is unknowable, having died not solving its riddles.

Strangely, his treatise instead offers a logically coherent and brilliant worldview of someone who has found his answers as far as human existence is concerned. Khayyam even goes so far as confidently saying he hopes his peers would agree that his brief treatise is more useful than volumes.

Offering the Persian text and my new English translation of the treatise, I undertook in the fourth book a detailed clause-based hermeneutic study of the treatise. I also explored its broader intellectual and historical contexts by examining its relation to the book “Savior from Error” by Khayyam’s junior (by more than three decades) contemporary foe, Muhammad Ghazali, while questioning the long-held belief that the treatise was requested by and addressed to Fakhr ol-Molk, a son of the famous vizier Nezam ol-Molk.

I found instead that the treatise was written in AD 1095-96, a few years earlier than thought, for another son of Nezam ol-Molk, Moayyed ol-Molk, who served at the time Soltan Muhammad, Malekshah’s son. The treatise was intended as a philosophical foundation to move the post-Malekshah Iran in a more independent direction by way of influencing his son, Muhammad.

In his book, likely written to please Ahmad Sanjar (Malekshah’s younger son who disliked Khayyam) and his vizier at the time, Fakhr ol-Molk, Ghazali anonymously chastised Khayyam as a philosopher, duplicitously feeding the cynical metaphors that some theologians and Sufis hurled at Khayyam down the centuries.

Khayyam’s treatise unveils his vision of existence as a participatory universe where the subject has objective status, shedding a new light on the ontological structures of the Robaiyat.

His “succession order” thesis of existence is an alternative Islamic creationist-evolutionary worldview that offers a prescient quantum conceptualist vision of the universe as a unitary, relatively self-reliant, self-knowing, and self-creative, substance lovingly created by an absolutely good God in His own image.

Existence is essentially good but, due to its good volitionally self-creative nature, can be potentially subject to incidental defects that are nevertheless knowable and curable to build both a spiritually fulfilling and a joyful life in this world.

Other than God’s Necessary Existence there is no “another world”; judgment days, heavens, and hells are definitely real this-worldly, not otherworldly, existents.

In Khayyam’s view, human existence can be what good we artfully make of it, starting here-and-now from our own personal selves in our this-worldly lifetimes. It is to creatively realize such an existence that the Robaiyat must have been intended.

5. Summary of Book 5: Khayyami Theology

The fifth book of the series was subtitled Book 5: Khayyami Theology: The Epistemological Structures of the Robaiyat in All the Philosophical Writings of Omar Khayyam Leading to His Last Keepsake Treatise.

The fifth book of the series was subtitled Book 5: Khayyami Theology: The Epistemological Structures of the Robaiyat in All the Philosophical Writings of Omar Khayyam Leading to His Last Keepsake Treatise.

Book 5 was devoted to an in-depth examination of all of Omar Khayyam’s philosophical treatises written before and leading to his last keepsake treatise on the science of the universals of existence which I had examined already in depth in Book 4 of the series.

The purpose of the study of these texts, applying the quantum hermeneutic method developed for the series, was to arrive at an understanding of the structures of the theological epistemology informing any collection of quatrains or Robaiyat Khayyam may have written in his life.

In the book, to understand the theological epistemology (or, way of knowing God) framing Khayyam’s Robaiyat as spread out in all his philosophical works, I offered the texts and my updated Persian and new English translations and analyses of six writings that preceded Khayyam’s last treatise on the universals of existence.

The six primary texts included:

1: Khayyam’s annotated Persian translation of Avicenna’s sermon in Arabic on God and creation;

2: Khayyam’s treatise in Arabic addressed to Nasawi (who I showed has been wrongly regarded as an Avicenna pupil) on the created world and worship duty;

3-5: Khayyam’s three treatises in Arabic (which I showed were all addressed to Abu Taher, to whom Khayyam also dedicated his treatise in algebra) that are separate chapters of a three-part treatise on existence on topics such as the necessity of contradiction, determinism, survival, attributes of existents, and the light of intellect on ‘existent’ as the subject matter of universal science; and

6: Khayyam’s treatise in Arabic addressed to Moshkavi (who I revealed was a supportive Shia intellectual) in response to three questions on soul’s survival, on the necessity of accidents, and on the nature of time.

In the book, I showed that the most fruitful way of understanding Khayyam’s six texts is by regarding them as efforts made at defending his “succession order” thesis implicitly revealed when commenting on Avicenna’s sermon and finalized in his last keepsake treatise. The texts served to offer the theological epistemology behind Khayyam’s thesis, revealing his creative conceptualist view of existence that informed his poetic way of going about knowing God, creation, and himself within a unitary Islamic creationist-evolutionary worldview.

It was learned that Khayyam’s way of knowing God and existence is non-dualistic, non-atomistic, and unitary in worldview, allowing for subject-included objectivity, probabilistic determinism, transcontinuous (or ‘discontinuous’) creative causality, transdisciplinarity, and transculturalism; it thus fulfils in a prescient way all the eight attributes of the quantum vision (Tamdgidi 2020).

Poetry is most conducive to unitary knowing, and subject-included objectivity must necessarily be self-reflective and thus engage intellective, emotional, and sensible modes of knowing.

This explains why Khayyam transcended scholastic learning in favor of a poetic encounter with reality. What he meant by ‘Drunkenness,’ calling it the highest state of mind known to him, can thus be best understood as a unitary, quantum state of mind achieved by way of his poetry as a meditative art of self-purification (what he called “tazkiyeh-ye nafs”).

The goal, metaphorically, is to move from a way of knowing things as divisible grapes to a pure and unitary way of knowing them as indivisible Wine—paralleling what we call today moving from chunky Newtonian toward unitary quantum visions of reality.

I posited that the key for entering Khayyam’s secret tent is realizing that what he primarily meant by ‘Wine’ in his Robaiyat was self-referentially his Robaiyat itself, a key openly hidden therein thanks to his theological epistemology.

For him, the Robaiyat was a lifelong work on himself, serving also human spiritual awakening to its place and duty in the succession order of God’s creation. It also served his aspiration for a lasting soul. He knew the now-proven worth of his secret magnum opus, and that is why he so much praised his ‘Wine.’

6. Summary of Book 6: Khayyami Science

The sixth book of the series was subtitled Book 6: Khayyami Science: The Methodological Structures of the Robaiyat in All the Scientific Works of Omar Khayyam.

The sixth book of the series was subtitled Book 6: Khayyami Science: The Methodological Structures of the Robaiyat in All the Scientific Works of Omar Khayyam.

In Book 6, I shared the Arabic texts, my new English translations (based on others’ or my new Persian translations, also included in the volume), and hermeneutic analyses of five extant scientific writings of Khayyam: a treatise in music on tetrachords; two treatises on balance, one being on how to measure the weights of precious metals in a body composed of them; a treatise on dividing a circle quadrant to achieve a certain proportionality; a treatise on classifying and solving all cubic (and lower degree) algebraic equations using geometric methods; and a treatise on explaining three postulation problems in Euclid’s book Elements.

Khayyam wrote three other non-extant scientific treatises on nature, geography, and music, while a treatise in arithmetic is differently extant since it influenced the work of later Islamic and Western scientists. His work in astronomy on solar calendar reform is also differently extant in the calendar used in Iran today. A short tract on astrology attributed to him has been neglected.

I studied the scientific works in relation to Khayyam’s own theological, philosophical, and astronomical views. The study revealed that Khayyam’s science was informed by a unifying methodological attention to ratios and proportionality.

So, given such a way of thinking, likewise, any quatrain he wrote cannot be adequately understood without considering its place in the relational whole of its parent collection. Khayyam’s Robaiyat is found to be, as a critique of fatalistic astrology, his most important scientific work in astronomy rendered in poetic form.

Studying Khayyam’s scientific works in relation to those of other scientists out of the context of his own philosophical, theological, and astronomical views, would be like comparing the roundness of two fruits while ignoring that they are apples and oranges. Khayyam was a relational, holistic, and self-including objective thinker, being systems and causal-chains discerning, creative, transdisciplinary, transcultural, and applied in method.

He applied a poetic geometric imagination to solving algebraic problems and his logically methodical thinking did not spare even Euclid of criticism. His treatise on Euclid unified numerical and magnitudinal notions of ratio and proportionality by way of broadening the notion of number to include both rational and irrational numbers, transcending its Greek atomistic tradition.

I argued that Khayyam’s classification of algebraic equations, being capped at cubic types, tells of his applied scientific intentions that can be interpreted, in the context of his own Islamic philosophy and theology, as an effort in building an algebraic and numerical theory of everything that is not only symbolic of body’s three dimensions, but also of the three-foldness of intellect, soul, and body as essential types of a unitary substance created by God to evolve relatively on its own in a two-fold succession order of coming from and going to its Source.

Although the succession order poses limits, as captured in the astrological imagination, existence is not fatalistic. Khayyam’s conceptualist view of the human subject as an objective creative force in a participatory universe allows for the possibility of human self-determination and freedom depending on his or her self-awakening, a cause for which the Robaiyat was intended.

Its collection would be a balanced unity of wisdom gems ascending from multiplicity toward unity using Wine and various astrological, geometrical, numerical, calendrical, and musical tropes in relationally classified quatrains that follow a logical succession order.

7. Summary of Book 7: Khayyami Art

The seventh book of the series was subtitled Book 7: Khayyami Art: The Art of Poetic Secrecy for a Lasting Existence: Tracing the Robaiyat in Nowrooznameh, Isfahan’s North Dome, and Other Poems of Omar Khayyam, and Solving the Riddle of His Robaiyat Attributability.

The seventh book of the series was subtitled Book 7: Khayyami Art: The Art of Poetic Secrecy for a Lasting Existence: Tracing the Robaiyat in Nowrooznameh, Isfahan’s North Dome, and Other Poems of Omar Khayyam, and Solving the Riddle of His Robaiyat Attributability.

In Book 7, I shared an updated edition of Omar Khayyam’s Persian book Nowrooznameh (The Book on Nowrooz), and for the first time my new English translation of it, followed by my analysis of its text. I then visited recent findings about the possible contribution of Khayyam to the design of Isfahan’s North Dome.

Next, I shared the texts, and my new English translations and analyses of Khayyam’s other Arabic and Persian poems. And finally, I studied the debates surrounding the attributability of the Robaiyat to Omar Khayyam.

In the book, I verifiably showed that Nowrooznameh is a book written by Khayyam, arguing that its unreasonable and unjustifiable neglect has prevented Khayyami studies from answering important questions about Khayyam’s life, works, and his times. Nowrooznameh is primarily a work in literary art, rather than in science, tasked not with reporting on past truths but with creating new truths in the spirit of Khayyam’s conceptualist view of reality.

Iran in fact owes the continuity of its ancient calendar month names to the way Khayyam artfully recast their meanings in the book in order to prevent their being dismissed (given their Zoroastrian roots) during the Islamic solar calendar reform underway under his invited direction.

The book also sheds light on the mysterious function of Isfahan’s North Dome, revealing it as having been to serve as a space, as part of an observatory complex, for the annual Nowrooz celebrations and leap-year declarations of the new calendar.

The North Dome, to whose design Khayyam verifiably contributed and in fact bears symbols of his unitary view of a world created for happiness by God, marks where the world’s most accurate solar calendar of the time was calculated.

It deserves to be named after Omar Khayyam (not Taj ol-Molk) and declared as a cultural world heritage site. Nowrooznameh is also a pioneer in the prince-guidance books genre that anticipated the likes of Machiavelli’s The Prince by centuries, the difference being that Khayyam’s purpose was to inculcate his Iranian and Islamic love for justice and the pursuit of happiness in the young successors of Soltan Malekshah.

Iran is famed for its ways of converting its invaders into its own culture, and Nowrooznameh offers a textbook example for how it was done by Khayyam.

Most significantly, however, Nowrooznameh offers by way of its intricately multilayered meanings the mediating link between Khayyam’s philosophical, theological, and scientific works, and his Robaiyat, showing through metaphorical clues of his beautiful prose how his poetry collection could bring lasting spiritual existence to its poet posthumously.

Khayyam’s other Arabic and Persian poems also provide significant clues about the origins, the nature, and the purpose of the Robaiyat as his lifelong project and magnum opus.

I argued that the thesis of Khayyam’s Robaiyat as a secretive artwork of quatrains organized in an intended reasoning order as a ‘book of life’ serving to bring about his lasting spiritual existence can solve the manifold puzzles contributing to the riddle of his Robaiyat attributability.

I posited that the lost quatrains comprising the original collection of Robaiyat have become extant over the centuries, such that we can now reconstruct, by way of solving their 1000-piece jigsaw puzzle, the collection as it was meant to be read as an ode of interrelated quatrains by Omar Khayyam.

8. Summary of Book 8: Khayyami Robaiyat: Part 1 of 3: Songs of Doubt

The eighth book of the series was subtitled Book 8: Khayyami Robaiyat: Part 1 of 3: Quatrains 1-338: Songs of Doubt Addressing the Question “Does Happiness Exist?”: Explained with New English Verse Translations and Organized Logically Following Omar Khayyam’s Own Three-Phased Method of Inquiry.

The eighth book of the series was subtitled Book 8: Khayyami Robaiyat: Part 1 of 3: Quatrains 1-338: Songs of Doubt Addressing the Question “Does Happiness Exist?”: Explained with New English Verse Translations and Organized Logically Following Omar Khayyam’s Own Three-Phased Method of Inquiry.

In Book 8, following a common introduction in which I shared the general guidelines about and an overview of the presentation of Khayyami Robaiyat in this series, I began by offering the first of a three-part set of 1000 quatrains I have chosen to include in this series from a wider set that have been over the centuries attributed to Khayyam.

Part 1 included quatrains 1-338 for each of which the Persian original along with my new English verse translation and a transliteration for the same were shared. Each quatrain was then indexed according to the frequency of its inclusion in manuscripts, the earliest known date of its appearance in them, the extent to which it has “wandered” into other poets’ works, and its rhyming scheme.

Brief comments about the meaning of each quatrain in relation to other quatrains and works attributed to Khayyam were then offered along with any notes regarding its new translation as shared.

I showed that the quatrains 1-338, in the beginning 30 quatrains of which Khayyam offers an opening to his book of poetry as a secretive work of art, address the question “Does Happiness Exist?” The latter question is the first of a set of three methodically phased questions Khayyam has identified in his philosophical works as being required for investigating any subject.

The order in which the quatrains were presented showed that the quatrains included in Part 1 follow a logically inductive reasoning process through which Khayyam delves from the surface portraits of unhappiness to their deeper chain of causes in order to answer his question. The thematic topics of the quatrains of Part 1 as shared in Book 8 were: I. Secret Book of Life; II. Alas!; III-Times; IV-Spheres; V. Chance and Fate; VI. Puzzle; VII. O God!; VIII. Tavern Voice; and IX. O Wine-Tender!

After the opening quatrains where Khayyam explained why he was composing a secretive book of poetry and what it aims to do, his inquiry started with doubtful existential self-reflections on his life, leading him to first blame his times, then the spheres, then matters of chance and fate, soon realizing that he really did not have an explanation for the enigmas of existence, concluding that the answer only lies with God. So, he appealed to God directly for an answer.

It is then that he heard the voice of the Saqi from his inner “tavern,” to whom he replied in a series of quatrains closing Part 1. It is in the course of the inquiry in Part 1 that the idea of using Wine as a poetic trope was discovered by him, a matter that is separate from his interest in drinking wine, which he never denied but is secondary to the Wine discovered and advanced in his book of poetry that in fact represents his poetry, the Robaiyat, itself and its promise in answering his questions.

The logical order of Khayyam’s inquiry showed how seemingly contradictory views that have been attributed to him can in fact be explained as logical moments in the successively deeper inquiries he made inductively when addressing the question whether happiness exists in the created world.

His inquiry is at once personal and world-historical, as two sides of expression of the human search for an answer. We should, therefore, judge each quatrain as a logical moment in Part 1’s inquiry as a whole, in anticipation of the two remaining parts of his book of poetry to be shared in Books 9 and 10 of the series, respectively addressing the two follow-up questions: “What Is Happiness?” and “Why Does (or Can) Happiness Exist?”

9. Summary of Book 9: Khayyami Robaiyat: Part 2 of 3: Songs of Hope

The ninth book of the series was subtitled Book 9: Khayyami Robaiyat: Part 2 of 3: Quatrains 339-685: Songs of Hope Addressing the Question “What Is Happiness?”: Explained with New English Verse Translations and Organized Logically Following Omar Khayyam’s Own Three-Phased Method of Inquiry.

The ninth book of the series was subtitled Book 9: Khayyami Robaiyat: Part 2 of 3: Quatrains 339-685: Songs of Hope Addressing the Question “What Is Happiness?”: Explained with New English Verse Translations and Organized Logically Following Omar Khayyam’s Own Three-Phased Method of Inquiry.

In Book 9, following a common introduction in which I shared the general guidelines about and an overview of the presentation of Khayyami Robaiyat in this series, I continued by offering the second of a three-part set of 1000 quatrains I have chosen to include in this series from a wider set that have been over the centuries attributed to Khayyam.

Part 2 included quatrains 339-685 for each of which the Persian original along with my new English verse translation and a transliteration for the same were shared. Each quatrain was then indexed according to the frequency of its inclusion in manuscripts, the earliest known date of its appearance in them, the extent to which it has “wandered” into other poets’ works, and its rhyming scheme.

Brief comments about the meaning of each quatrain in relation to other quatrains and works attributed to Khayyam were then offered along with any notes regarding its new translation as shared.

I showed that the quatrains 339-685 address the question “What Is Happiness?” The latter is the second of a set of three methodically phased questions Khayyam has identified in his philosophical works as being required for investigating any subject.

The order in which the quatrains were presented showed that the quatrains included in Part 2 follow a logically deductive reasoning process through which Khayyam advances in the causal chain of moving from methodological to explanatory and practical quatrains, by way of addressing the question noted above.

The thematic topics of the quatrains of Part 2 as shared in Book 9 were: X. The Drunken Way; XI. Willfulness; XII. Foes and Friends; XIII. Wealth; XIV. Today; XV. Pottery; XVI. Cemetery; and XVII. Paradise and Hell.

Khayyam began with reflections on God’s created world, suggesting that its unitary existence cannot be understood using either/or dualistic lenses where the ways of knowing by the head, the heart, and senses are pursued separately.

Instead, he advocated, building on the idea of the Wine trope discovered in Part 1, a “Drunken way” by which he meant a unitary way of knowing symbolized by the spiritual indivisibility of Wine in contrast to the fragmentations of the grapes. He then embarked on a deductive method of emphasizing human willfulness, also created by God, offering humankind a chance to play a creative role in shaping its world.

He then continued to apply such an explanatory model in dealing with practical social matters having to do with foes, friends, and wealth, leading him to advocate for the practical significance of “stealing” the chances offered in our todays to transform self and society in favor of happier and more just outcomes.

Using the tropes of visiting the jug-maker’s shop and the cemetery, Khayyam then emphasized the need to maintain a wakeful awareness of the inevitability of one’s physical death in order to use the opportunity of life to cultivate universal self-awareness before it is too late, positing that paradise, hell, and judgment days are not otherworldly, but realities of our here and now living.

He thus transcended the sentiment of a promised future hope by advising us to create a happy life in the cash of the present, his own poetry itself being a means toward that end. Part 2 must then be understood in consideration of the other two parts of his book of poetry, one shared in Book 8 addressing the questions “Does Happiness Exist?” and the next to follow in Book 10 addressing the question “Why Does (or Can) Happiness Exist?”

10. Summary of Book 10: Khayyami Robaiyat: Part 3 of 3: Songs of Joy

The tenth book of the series was subtitled Book 10: Khayyami Robaiyat: Part 3 of 3: Quatrains 686-1000: Songs of Joy Addressing the Question “Why Can Happiness Exist?”: Explained with New English Verse Translations and Organized Logically Following Omar Khayyam’s Own Three-Phased Method of Inquiry.

The tenth book of the series was subtitled Book 10: Khayyami Robaiyat: Part 3 of 3: Quatrains 686-1000: Songs of Joy Addressing the Question “Why Can Happiness Exist?”: Explained with New English Verse Translations and Organized Logically Following Omar Khayyam’s Own Three-Phased Method of Inquiry.

In Book 10, following a common introduction in which I shared the general guidelines about and an overview of the presentation of Khayyami Robaiyat in this series, I continued by offering the third of a three-part set of 1000 quatrains I have chosen to include in this series from a wider set that have been over the centuries attributed to Khayyam.

Part 3 included quatrains 686-1000 for each of which the Persian original along with my new English verse translation and a transliteration for the same were shared. Each quatrain was then indexed according to the frequency of its inclusion in manuscripts, the earliest known date of its appearance in them, the extent to which it has “wandered” into other poets’ works, and its rhyming scheme.

Brief comments about the meaning of each quatrain in relation to other quatrains and works attributed to Khayyam were then offered along with any notes regarding its new translation as shared.

I showed that the quatrains 686-1000 address the question “Why Does (or Can) Happiness Exist?” The latter question is the third of a set of three methodically phased questions Khayyam has identified in his philosophical works as being required for investigating any subject.

The order in which the quatrains were presented showed that the quatrains included in Part 3 continue the logically deductive reasoning process started in Part 2, but serve as practical examples of how humankind can turn the activity of poetry writing itself as a source of joy in life when confronting the topics of death, survival, and spiritual fulfillment.

The thematic topics of the quatrains of Part 3 as shared in Book 10 were: XVIII. Garden; XIX. Wine; XX. Love; XXI. Night; XXII. Death and Survival; XXIII. Liberation; and XXIV. Return.

Khayyam’s overall sentiment in pursuing the inquiry in the third part of his book of poetry was expressive of joy. He began by showing, using the example of his own poetry, how strolling in a garden offers opportunities to enjoy life even when writing about the transient nature of the roses and greens.

He then offered in the longest section of his book of poetry a set of quatrains in praise of Wine, disguising therein a praise of the joy of writing his own poetry, Wine’s metaphorical double-meanings offering chances in the here-and-now of “stealing” joyfulness even amid feelings of helplessness in confronting physical death.

He then turned to the topic of spiritual Love, signifying the role the sentiment of Love in search of the Source of creation plays in the evolutionary movements back and forth of the succession order of the created existence as discussed in his philosophical and theological writings.

Khayyam then turned to the topic of death and the possibility of lasting spiritual survival and existence by practically encouraging the Drinkers of the Wine of his poetry itself to help bring about that end.

He ended the Wine of his poetry by expressing how it has helped free himself from the prior (in Part 1) doubtfully expressed inevitability of physical death in favor of not just hopefulness (in Part 2) but the certainty of having initiated a lasting spiritual existence by way of the bittersweet Wine of his poetry itself, celebrating a return to the spiritual Source of all existence as woven into the 1000-threaded wick of the candle of his Love for God.

We should therefore judge each step of the third part of Khayyam’s poetic inquiry in consideration of the two other parts of his book of poetry, those shared in Books 8 and 9 addressing the questions “Does Happiness Exist?” and “What Is Happiness?”

The eleventh book in the series was subtitled Khayyami Robaiyat: Re-Sewing the Tentmaker’s Tent: 1000 Bittersweet Wine Sips from Omar Khayyam’s Tavern of Happiness.

11. Summary of Book 11: Khayyami Robaiyat as a Whole

The eleventh book of the series was subtitled Book 11: Khayyami Robaiyat: Re-Sewing the Tentmaker’s Tent: 1000 Bittersweet Wine Sips from Omar Khayyam’s Tavern of Happiness.

The eleventh book of the series was subtitled Book 11: Khayyami Robaiyat: Re-Sewing the Tentmaker’s Tent: 1000 Bittersweet Wine Sips from Omar Khayyam’s Tavern of Happiness.

In Book 11, following a common introduction in which I shared the general guidelines about and an overview of the presentation of Khayyami Robaiyat in this series, and having shared the three parts of the Robaiyat attributed to Khayyam in the Books 8, 9, and 10 of the series, I offered the entire set of the 1000 quatrains, including the Persian originals and their new English verse translations.

The poems, comprising Khayyam’s songs of doubt, hope, and joy, were organized according to the three-phased method of inquiry he introduced in his philosophical writings, respectively addressing the questions: “Does Happiness Exist?”; “What Is Happiness?” and “Why Can Happiness Exist?”

When Khayyam discussed the three-phased method of inquiry in his treatise “Resalat fi al-Kown wa al-Taklif” (“Treatise on the Created World and Worship Duty”), he noted an exception to the rule of asking, when studying any subject, whether it exists, what it is, and, why it exists (or can exist).

He distinguished between things objectively existing independent of the human mind, and those created by the human mind. The normal procedure applies to the former, but for products of the human mind, he advised, the procedure must be modified to asking first what something is, then, whether it exists, and, then, why it exists or can exist.

This is because, for products of the human mind, such as created works of art, we would not know whether something exists and why it exists unless we first know what it is. To illustrate his point, he used the example of the mythical bird ʿAnqāʾ (standing for Simorgh in Persian or the Phoenix in English).

He argued that only when we know what the metaphor stands for, would we be able to say whether it exists (say, in a work of art, or even as a person represented by it), and why it exists or can exist.

Khayyam’s elaboration implies that one has to make a distinction between objective and human objectified realities, which implies that for some objects, such as happiness, we in fact confront a hybrid reality where aspects of it may be externally conditioned, but other aspects being dependent on the human will.

Once we realize the significance of Khayyam’s point, then, we appreciate that his Robaiyat can also be regarded as a way of poetically portraying and advancing human happiness, its poetic Wine being not just reflective but also generative of the happiness portrayed.

By way of his poetry, therefore, Khayyam has offered a severe critique of the then prevalent fatalistic astrological worldviews blaming human plight on objective conditions, in favor of a conceptualist view of reality in which happiness can be achieved despite the odds, depending on the creative human agency, itself being an objective force.

I further showed that the triangular geometry of the logic governing Khayyam’s Robaiyat—the numerical values of whose three sides (that is, of the number of quatrains each side contains) are proportional to the Grand Tent governing Khayyam’s birth chart (as studied in Books 2 and 3 of this series)—is expressive of the fact that for him his Robaiyat poetically represented the tent of which he regarded himself to be a tentmaker, revealing another key source of his pen name.

I showed that the metaphor of the Robaiyat as Simorgh songs is hidden in the deep structure of Khayyam’s 1000-piece solved puzzle, the same way he embedded his own triangular golden rule in the design of the North Dome of Isfahan, as shown in Book 7 of the series. Khayyam’s Robaiyat are his Simorgh’s millennial rebirth songs served in his tented tavern as 1000 sips of his bittersweet Wine of happiness.

12. Summary of Book 12: Khayyami Legacy

The the twelfth book of the series was titled Book 12: Khayyami Legacy: The Collected Works of Omar Khayyam (AD 1021-1123) Culminating in His Secretive 1000 Robaiyat Autobiography. Book 12 condensed the series and its findings in a single volume.

This was the first time since Omar Khayyam’s passing that all his extant works have been compiled in a single publication series and volume and studied integratively, accomplished just in time for the millennium of his true birth date and the ninth centennial of his true date of passing.

It included two forewords, one by Winston E. Langley, Professor Emeritus of Political Science and International Relations and former Provost of UMass Boston, and another by Jafar Aghayani Chavoshi, Professor of History of Science and Mathematics at Sharif University of Technology in Tehran.

The original texts were included with their new English (and where needed, updated or new Persian) translations. The preface recapped how a method in quantum sociological imagination helped solve the riddles of Khayyam’s life and works in the series.

The introduction delineated this series’ findings toward a scientifically reliable biography of Khayyam, including a critical commentary on how Edward FitzGerald’s Rubaiyat colonially distorted Khayyam’s Robaiyat and Islamic legacy.

Three other chapters were also shared: one on how Khayyam’s true dates of birth and passing were discovered and reconfirmed in this series, including further notes on Swami Govinda Tirtha’s errors in studying Khayyam’s birth horoscope for the purpose; another on integratively viewing astronomy and its relation to astrology amid all of Khayyam’s works; and a third on the role he played in the design of Isfahan’s North Dome.

Khayyam’s studied writings were: his treatise on the science of the universals of existence; his annotated Persian translation of Avicenna’s “Splendid Sermon” on God’s unity and creation; his treatise on the created world and worship duty; his three-part treatises on existence (1-on the necessity of contradiction, determinism, and survival; 2-on attributes; and 3-on the light of intellect on ‘existent’ as the subject matter of universal science); his treatise on soul’s survival, necessity of accidents, and nature of time; his treatise in music on tetrachords; his two treatises on balance; his treatise on circle quadrant for achieving a certain proportionality; his treatise in algebra and equations; his treatise on Euclid’s postulation problems; his literary treatise “Nowrooznameh”; and his secretive autobiography, the Robaiyat, comprised of 1000 quatrains logically organized based on his own three-phased method of inquiry.

This series found the answer to its question about the origins, nature, and purpose of the Robaiyat in Khayyam’s life and works. Lifelong, he was secretively writing his Robaiyat as his “book of life,” his autobiography, for posthumous release. His pen name “Khayyam” (“tentmaker”) had been inspired by his dazzling birth chart.

By re-sewing in this series his autobiographical tent of wisdom as a Tavern serving the spiritual Wine of his poetry, we have advanced from knowing little about his life to reading his most intimate autobiography. But the Robaiyat is not just a private autobiography; it is also a sociologically imaginative and poetic public telling of humanity’s search for a universal healing.

Iran’s appreciation of Omar Khayyam’s legacy can be best judged not by the physics of his burial sites, traditionally humble or artistically modern, but by the role Iranians themselves have played since his time in safeguarding his works especially in the poetic bricks and mortars of the human architecture of his own secretly designed and designated everlasting tomb.

Foreword by Winston E. Langley to the Last Book of the Series

Omar Khayyam’s Secret, of which “Toward A Textually and Historically More Reliable Biography of Omar Khayyam” is an introduction to its final volume, is a twelve-book series on a special world-historical figure, Omar Khayyam.

This 11th/12th centuries Persian (Iranian) sage, astronomer, mathematician, philosopher, physician, writer, and poet has been known to the world, but only partially; and this partial knowledge of him has been riddled with cultural, historical, methodological, personal, political, and sociological problems, most or all of which have served, deliberately or inadvertently, to obscure, distort, fragment, or otherwise inaccurately portray him and what he sought to teach the world.

This twelve-book series by Mohammad H. Tamdgidi, has effectively established the basis to put an end to these inaccuracies; and the manner in which it has done so should make the series a source of learning and reference for the next thousand years and beyond, starting from now. Every college library should at least secure a copy of the last synoptic volume of the series; and every research library should have the entire series as one of its prized acquisitions and holdings. After all, the series shares and studies all the extant works of Omar Khayyam in the original Persian and Arabic with their new English (and where needed, updated or new Persian) translations, and does so again along with summaries of its findings in its final synoptic volume.

The claim or assertion respecting the likely longevity of the series and its importance to libraries (and, by implication, scholars) is not made lightly, and it is in no way an exaggeration. A study of its methodology, its findings, the significance of those findings for the universe of learning, of the skills, dedication, and sacrifices the author brought to bear on the work, and of the approach observed to help readers grapple with and understand what is being disclosed, attests a rich body of corroborating testimony to the assertion.

In the case of methodology, for instance, the series is grounded on what Tamdgidi calls the “quantum sociological imagination” (QSI). This view, like quantum (subatomic) physics—which shows that particles can exist in multiple states simultaneously, are entangled and interconnected regardless of distance, and will dissolve or collapse on being observed—bears resemblance to human imagination and creativity which similarly allow for multiple (often) simultaneous states. In addition, human imagination and consciousness are at once personal, social and spiritual, and encompassing patterns of social relationships.

Moreover, Tamdgidi, in order to make QSI broadly understandable and concretely applicable to a wide range of lived experiences, contrasts it with the overwhelmingly binary culture that has defined modernism (which he calls Newtonian mode of imagining). He grapples with this contrast by using an eight-feature vision of the QSI—used in each book—that details and nurtures a non-dualistic, trans-continuous, transdisciplinary, transcultural, subject-included objectivity, as well as simultaneous and unitary modes of knowing and being. In short, the series rejects the alienating, fractionalizing, disintegrating, yes-no, or up-down, habits of Newtonian dualistic outlook, including that outlook’s presence in academic life, in the form of disciplines (biology, chemistry, history, music, physics, sociology) that have engaged in narrow, non-continuous assessments, or bodies of knowledge, which find it irrational to accept contradictions—an attribute that may, in fact, be part of an illuminating, underlying unity.

As a graduate student pursuing answers to the question of why the religious, scientific, and philosophic traditions had failed in their efforts to create societies that are productive of human liberation and a just global order, Tamdgidi had come to the conclusion that this failure had resulted not only from the mutually alienating or separating constitution and practices of these traditions, but, as well, out of the inner fragmentation of body, mind, and feelings from one another, at the personal level. It was in the pursuit of this uncovered insight that he gained a new sense of Khayyam and decided to devote his attention to the study of his work. That devotion has included decades-long studies, the establishment of an Omar Khayyam Center, the creation of a journal, Human Architecture: Journal of Sociology and Self-knowledge, as well as his giving up a successful, tenured professorship at a research university.

Among the results of consistently following the QSI methodology is that of the immense achievement of its help to end the impasse that had developed in Khayyam studies, in discovering and reconfirming the dates of his birth and death (1021-1123), accounting for and verifying of the body of works attributed to him in art, astronomy, medicine (as shared in his “Nowrooznameh” and implied in his poetry’s stated healing aims), music, philosophy, science and poetry, including his authorship of the Robaiyat (on which we will later touch). Book one of the series, for example, introduces the series and the QSI method, as developed by Tamdgidi. The second book focuses on presenting the discovery and reconfirmation of Khayyam’s birth and death dates, while book three discloses how that discovery (along with horoscopic origins of pen name) led to the independent confirmation of “his authorship of a collection of robaiyat.”

The fourth book, written to report on a Khayyam keepsake, is centered around his treatise on the science of the universals of existence; and the fifth, subtitled Khayyami Theology constitutes a thorough examination of Khayyam’s philosophical treatises (written before his keepsake) that focus on understanding the structure of theological epistemology, which is, how one comes to know God. Book six of the series seeks, through its deft hermeneutic insights, to help readers gain discernments into the methodological organization of Khayyam’s scientific thinking and the illuminations it offers to his literary works, particularly his poetry writing. (The book contains analyses of five extant scientific writings of Khayyam in the form of treatises, including one on music, two on balance one of which shows how to measure the weights of precious metals in a body composed of them, one on how to divide a circle quadrant to obtain “a certain proportionality,” a treatise on how to classify and solve all cubic (and lower degree) algebraic equations using geometric methods, and a treatise explaining three postulation problems of Euclid.)

Books seven to ten add stirringly to a reader’s appreciation of the series. In number seven, entitled Khayyami Art, Tamdgidi shares with the reader his updated edition of Khayyam’s Persian book, “Nowrooznameh,” and, “for the first time his [own] new English translation of it,” followed by an exacting analysis of its text and the recent findings concerning Khayyam’s possible contribution to the magnificent design of Isfahan’s North Dome. In books eight to ten, the reader encounters a three-part presentation of a set of 1,000 quatrains, chosen to be included in the series from a wider set, that has, for centuries, been attributed to Khayyam. Part 1 (book 8) covers quatrains 1-338; part 2 (book 9) encompasses quatrains 339-685; and part 3 (book 10) comprises quatrains 686-1,000, with each body or grouping of quatrains, respectively, addressing “songs of doubt” and the question of whether happiness exists, “songs of hope” and the issue of what is happiness, and “songs of joy” addressing the question of why can happiness exist. (Each of the quatrains, in the three sets, has its Persian original. Each is also accompanied by Tamdgidi’s new English verse translation and transliteration, along with indexes and comments.)

In book eleven of the series, Tamdgidi, emulating the metaphors of its title, Khayyami Robaiyat: Re-Sewing the Tentmaker’s Tent, offers the entire (sewn together) set of 1,000 quatrains in their Persian originals and his new English verse translation of each. A poetic triumph.

I went into the above relative details concerning the series to facilitate a number of observations in the company of which we can make, in this review, but a few about both Khayyam and the author of the series. In respect of the latter, in addition to the extraordinary dedication and sacrifice already mentioned, one must note that it is his transdisciplinary methodology—imbedded in the QSI—which enabled the study and discoveries (ably told throughout the series and outlined in book 12) that go to the offering to the world of the Khayyam that has emerged. It is also due to the immense technical and cultural expertise he possesses and has so adeptly deployed from his background in engineering, architecture, social sciences and the humanities to roam across Khayyam’s work—from algebra, astronomy, and medicine, to music, philosophy, poetry, and writing.

At the cultural level, he brought to bear his historical and linguistic gifts, translating and transliterating Khayyam’s original works from Arabic, Persian, or both into English. As well, Tamdgidi argues that there is always a link between some personal troubles of a creator and social life that gives birth to creative achievements; and, throughout the series (and elaborated and enriched in his comments on the biography of Khayyam in the twelfth book of the series), he demonstrates how this claim is applicable to Khayyam, including the secrecy (and the reasons for it) involved in Khayyam’s writing of the Robaiyat.

Finally, the series is a most admirable example of teaching at its best. Tamdgidi is but an expert guide in a journey of joint learning and teaching; nowhere, except in the concluding book, including his notes on the biography of Omar Khayyam, is it conclusory. He patiently anticipates and works with the reader to grapple with issues, so there are common discoveries. At times, he and his readers are detectives, with moments of sudden insights, realizations, and inspiration. Indeed, for this reader, who was exposed at an early age to Khayyam, through the work of Edward FitzGerald, encountering this series was like the astronauts who experienced seeing the Earth for the first time from outer space. It was nothing I could have imagined, from prior experience.

Tamdgidi, having taken his readers through the first eleven books, in book twelve—consistent with good teaching—offers an overview of what had already been covered by the series, as he does in each successive book of the series. He does more. He discusses the scientific requirements for the study of Khayyam’s biography; and, then, he proceeds to depict the new findings of the series that make possible “a textually and historically more reliable biography for Khayyam.” Both, with distinction, he has achieved.

We turn to Khayyam and the significance of the series, each of which is entangled with the other. First, in Tamdgidi’s model of QSI, Khayyam (the tentmaker) had personal problems which interacted with public and cultural issues of his day, including certain forms of thinking within Islamic civilization, for which he otherwise had deep respect. Some of the thinking or differences (in part dealt with in book four), were unlikely to be resolved, especially in face of their fundamental character, the presence of political regime changes, and intellectual contemporaries, such as Muhammed Ghazali, who did not like him or whom he could not trust.

A second point of emphasis in dealing with Khayyam and the significance of the series is that he was a representative of the QSI as no other thinker, except in a limited way by authors of the Upanishads and in the Daoists tradition, with whom I have been acquainted. Readers will find, even in the sketch I have provided on the series, that when one is focusing on his study of art, science is present; and when one engages a treatise on science, literary source elucidations are made and (especially poetic) metaphorical strategies are being also pursued. To him, a scientific principle, a literary metaphor, and design sketch are interchangeable, and a single quatrain may contain all three, plus an irony with multiple meanings. Only a transdisciplinary and transcultural, as well as a trans-continuous, subject-participant mode of study, grounded on simultaneity and unity in parts of reality, could successfully understand his work.

Nobel Laureate Octavio Paz, in his Sor Juana (Sister Juana) offers readers a sweeping imagination and biography, but he confined himself to the humanities. Robert Kanigel in The Man Who Knew Infinity (mathematical genius Ramanujan) and H. S. Harris in his Hegel’s Ladder: The Odyssey of the Spirit offer steps and calibrations in their respective subjects’ imagination and thinking. Einstein and Tagore, in their exchanges about it, spoke of its superiority to the intellect in creativity, but in none of the instances mentioned does one find the comprehensiveness and integration of Khayyam. In his view, we have a participatory universe in which existence is at once unitary, self-creating, self-reliant, and inter-engaging.

In his work, especially his poetry, one finds the pathos of the tragedian, with the author of Gilgamesh, Sophocles, Shakespeare, and Goethe calling; one comes face to face with anxiety, doubt, and the absurd, and tastes Dostoevsky, Kierkegaard, Camus, and Kobo Abe; one confronts subtleties of the most refined kind and meets Buddha, Pushkin, and the practical genius of Da Vinci and Bacon; and one, confronted with the heart and matters of faith and reason, love and happiness, finds voices from Aristotle, St. Augustine, and Aquinas, to Zara Jacob, Jefferson, and Bonhoeffer. Happiness, for example, is not only a state of well-being, but a process of continuing liberation.

The general comprehensiveness mentioned in the preceding paragraph as an attribute of Khayyam’s work needs to be understood further, in a broad cultural sense and, additionally, in respect of the nature and purpose of the Robaiyat. The cultural feature has two parts—one we can state briefly, and another that requires some explanation. The succinct statement is that Khayyam was partly a Renaissance and Enlightenment figure centuries before either of these two pearls in the crown of Western civilization had developed.

The longer explanation has to do with a pattern of dualism that began with Persia’s far-reaching ancient military confrontations with Greek and (indirectly) Roman cultures at the 490 BCE Battle of Marathon, as a result of which those cultures had come to define themselves in terms of what Persia was supposedly not. The advent of Islam (and here one should recall the Crusades, the First of which took place during the lifetime of Khayyam) reinforced this constructed, excluding and binary worldview coming from Greece and Rome, as Europe and its Christian civilization defined themselves in terms of what Islam ostensibly was and is not. As an Islamic country, Iran (Persia) has partaken of this deep cultural othering and “other.”

In point of fact, Persia (Iran) was seen as part of an ascribed cliché culture that has been regarded as a potential negation of all European values. This negation partakes of an attributed general unsavoriness called “orientalism,” with people of the Orient (East) viewed as lazy, given to physical indulgence and pleasure, fatalistic, mysterious, untrustworthy, reticent, and untruthful. This is the pattern of thinking and being that Edward FitzGerald deliberately reinforced, as he presumably reluctantly sought and gained world-wide fame from sharing his distorted and distorting view of the Robaiyat. Tamdgidi’s series has the capacity to create a substantial break, once and for all, in this pattern.

The stereotyping of Persian (Iranian) culture, a rich and ancient culture, and localizing it, is all the more regrettable, because the nature and purposes of the Robaiyat—and here, Tamdgidi’s offering of a translated tri-partite and then, integrated, version of this poem (this epic) is of utmost importance—especially allow for readers’ interpretations which will be part of that thousand years (earlier referred to) discussion and interpretation. It was not written for Iran but for the world (hence the reactions of the world to FitzGerald’s work), not for a partial time, but for all times; not as poetry, only, but as an attempted integration of all his learning about humans (at the individual and species level), and the universe. The epic also serves as a meditation chamber, a dialogic laboratory, a riddle, within a puzzle, within an enigma to teach us about perplexity (above and beyond the personal need for secrecy), and the wine which lies behind hidden, committed involvement in journeys that are not single experiences of the intellect, but the entire symphony of feelings, emotions, passions that constitute the mixture of human possibilities. It is also an epistle on love, beauty, and activism, seeking to thwart the thinking that prevents one from seeing that a just and inclusive social order can be realized; a cathedral where the head, heart, and faith acknowledge that they are one; and a testimony of how suffering, through its dynamic revelatory intelligence, can operate through the individual as a public intellectual (not in the sense of Gramsci’s definition of the organic intellectual, although Khayyam may also be regarded as an organic intellectual of our common humanity, but in terms of one who avoids the pursuit of personal interests that are not consonant with the public’s good).

The Robaiyat is also an oracle, a medium through which advice and prophecy are given. Khayyam believed that within each of us are universal and multivalent bonds, part of a unified, vital and vitalizing universe, which urges the cultivating of humanity through critical self-examination, scientific skepticism, the ideal of moral responsibility implicit in global (human) citizenship, and development of the narrative imagination. (Martha Nussbaum in her Cultivating Humanity touches on this, but within the confines of Western classics and partly Newtonian practices.) His warning, his prophecy, is that unless we embody the dynamic unity (and its multivalent values, meanings, and other properties), rejecting the divisive, enfeebling separated and separating parts (be they individuals, nations, social classes, races, birth, gender, balance of power instead of the UN, for example), we are bound for destruction. Climate change, weapons of mass destruction, including nuclear weapons, and the abuse of one deemed “stranger” are inviting of our collective peril.

Fate and chance, dealt with throughout the series, including the autobiographical Robaiyat, are part of that which Khayyam saw as elements of our pilgrimage in life. Even in face of existential danger, however, we must summon the will or courage to act (and we hear Nietzsche’s applause here), knowing, as Alexander Pope—a spiritual kin of Khayyam—reminds us, that all of nature is art often unknown to us, with chance observing directions we do not immediately see.

While Khayyam’s life is a major story of fierce intellectual passion and a like devotion to ideals of philosophy, science, and poetry (and modes of living that combined those of the solitary and the celebrated, the private and the public), there is an area that is part of his identity that cannot be overlooked without an injustice to scholarship, history, and human culture. It is the role of satire—that which humorously criticizes defects of reason, science, philosophy (including theology), politics, history, custom (however sacred), even in face of deep disappointments or lived catastrophes. Welcoming the comedy, as Aristophanes, Cervantes, Vico, Erasmus, Santayana, and Chekhov knew, is part of coming to know, of wisdom, of ensuring human flourishing. One may say that Khayyam could be regarded as the first true humanist. All that is human find unhidden expressions through him.